Clifford V. Harrington. Photo © CliffEhnGee.

American-born actor-writer-photographer Clifford V. Harrington (1932-2013) is most recognizable to aficionados of Japanese monster movies as King Kong vs. Godzilla‘s Al, the terrified helicopter co-pilot who doesn’t know “what to make of it” when Godzilla bursts out of the iceberg. While he’s best known for that role, Mr. Harrington also appeared as an extra in Mothra (1961), dubbed kaiju eiga for William Ross’ dubbing company, and served as cinematographer on Robert Dunham’s independent sci-fi film Time Travelers (1966). At the time of this 2006 interview, Mr. Harrington was a resident of Kirkland, Washington (near Seattle), and spoke with Brett Homenick via telephone about his prolific career in Japanese films. (The photos that illustrate this interview were taken by Mr. Harrington during his time in Japan and are reproduced with permission.)

Brett Homenick: To begin with, tell me a little bit about your background.

Cliff Harrington: Well, I was born in Seattle, June 18, 1932, which makes me 74. I went to school in Seattle — you don’t know these places. Then in wartime, 1942, we moved to California, first Berkeley, where I really began going to movies. I used to go over to San Francisco on what was called the Key System Train that went across the Oakland Bay Bridge. I would go to movies over there, all kinds of movies! In Berkeley, I was going to local theaters because we were staying in a motel till we bought a house. Then in 1948, we moved to Santa Clara Valley, which is now called Silicon Valley, and I got into movie projectors. I think I had one in Seattle, a 16mm hand-crank DeVry projector. At Woolworths, for one dollar you could buy 25 feet of a Charlie Chaplin movie.

My friends and I had projectors, and we would sit in a staircase and project our movies in the dark because the staircase was closed with the door, and we would see movies, maybe there’d be eight of us. Actually, we moved back here (the Seattle area) eight years ago. I’ve been in touch with one of those kids who’s now 76 or so. Anyhow, I saw movies I was interested in, in Berkeley, 1942 and on. I had a movie camera after a couple of years, 8mm. I made some movies, 8mm to start with, with my friends. Then when I was a bit older, I had 16mm, and I made a movie in a kind of park in Berkeley. It was a city park, and it was like a jungle. We photographed in there, and I combined that with things from a Castle film. That was a company that sold movies to amateurs, showing lions and stuff, and we put that together to make a movie.

Then we moved to the Santa Clara Valley in 1948. By then, I was well into 16mm. I went on from there. After college, I made a trip to Mexico in the Yucatan Peninsula, and I photographed a boy who lived near the Mayan ruins of Chichen Itza, and we filmed in there. I believe at that time I had a Victor camera, which is 16mm. That movie was shown on a local TV station in San Francisco. I wrote about it for the American Cinematographer magazine. I think it was called “Our Movie on TV.” (laughs) Then because of that movie experience, I began writing for the American Cinematographer magazine, which was published by the American Society of Cinematographers, the ASC cameramen.

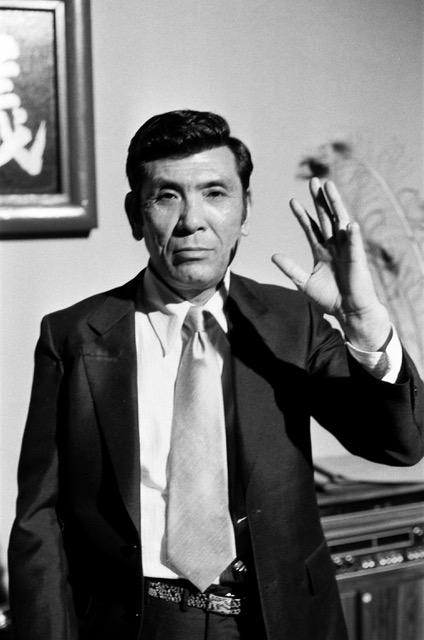

Nikkatsu actor Akira Kobayashi (right) in the early 1960s. Photo © CliffEhnGee.

I began submitting so many articles they made me a contributing editor. When I was inducted into the U.S. Army, a year or so after the Korean War, I wanted to go to the Signal Corps photo school in Ft. Monmouth, New Jersey. I got there and talked my way into the movie school. I got to work with 35mm Mitchell cameras. Then through a lucky break, we moved to the State of Washington here, Ft. Lewis. There was a guy in front of me, and there were three chances to go to the Far East. That fellow had forgotten some papers, and he said, “Save my place in line.” I said, “Well, you can be behind me. I’m moving up.” Because of that, I was able to select and got into Japan, and that put me in Japan for a little over a year. That was my first chance, by accident almost, to go and be in a Japanese movie, even though I was still in the army.

I was first at Camp Zama, and another fellow and I went to Yokohama, which is not too far away. I saw movie lights. It was at night, and they were making a movie on location there. The other guy wanted to leave, but I wasn’t about to leave. We were watching a real movie being made. The director was sitting in a chair. He noticed me, and he said something in English, “I wish those guys would hurry it up!” That was Yutaka Abe, who had been trained in Hollywood, therefore he spoke English, and he invited me to go out to Nikkatsu Studios, which I did later. Somehow I found my way in and everything. While I was there with Abe, (who) was a director of some prominence, a fellow came up who was not Japanese (I later found out was Turk) and asked if I was busy, and I said no. Well, he was one man short in a Nikkatsu movie, and he paid me to be in it. I forget how much. That was the first Japanese movie that I appeared in.

Nikkatsu star Hideaki Nitani (right) at the studio in the early 1960s. Photo © CliffEhnGee.

Then shortly after that, I also filmed 35mm stuff as an army cameraman. We had a Wall sound camera, sound on film, 35mm. And we also had Mitchells and the little Eyemo, which was a hand-held, 35mm combat camera.

I had a real grueling trip to Korea on a USO show to film Jane Russell. She was a Howard Hughes actress. I filmed her tour in Korea, and she asked for a movie cameraman because she was sponsoring a wing of an orphanage there, and that was one of her reasons for going. Because of that, she was then invited to President Syngman Rhee’s home to be thanked for her helping that orphanage. I filmed the President and his Austrian wife, and that was a real rough job, working for that beautiful lady. (laughs) Later, we had our picture taken, each of us with her. Then I got out of the army. I traveled on ships, which you could do then. Young people were traveling all over on ships rather economically. I saw Hong Kong, the Philippines where I stayed a month and did some work with some foreign people making a movie, and it was — oh, golly — the guy who played (in) Of Mice and Men. He was a New York theater actor. He also was in the first Rocky movie with Sylvester Stallone. He played the guy in his corner.

BH: Burgess Meredith?

CH: Yes, Burgess Meredith. I had a chance to photograph and talk to him, and the company bought a couple of my negatives to use in their film promotion. I got to Singapore and then over to Borneo where I lived with headhunters. I was photographing missionaries, but I got to live in a long house where skulls were hanging from the ceiling. Then I went back to San Francisco. I worked at a newspaper up in Pittsburg, California, for about a year. Then I decided to go back to Japan because I wanted to photograph the whaling fleet, both in stills and 16mm movies. And my friend, Henry Kotani, known as Henry, who had worked for Cecil B. DeMille in the Hollywood hand-crank days.

He had been adviser to the American army cameramen, and he was my sponsor. He used to say, “Come on, Cliff.” I’d never argue with him. He’d say, “Get your camera,” and he would take me out, and we’d photograph something. He told me stories about Donald Crisp and other people that he photographed. He would do the second negative. The first negative was for American distribution; the second negative was for foreign distribution of films. He put a young man to work who’d been a boxer, and that was James Wong Howe, the famous American cameraman. He was a very big name in movies when I was growing up, watching films.

Mr. Harrington on an Antarctic whaling expedition between December 1959 and February 1960. Photo © CliffEhnGee.

I went back to Japan with Henry Kotani’s sponsorship, and I got on the ships, went to the Antarctic, and made movies. I sold articles to the California Academy of Science magazine, Pacific Discovery. They had also published my articles on the headhunters in Borneo. I was only going to stay six months, and that was 1959. I came back to America in 1998. So I spent 40 years in Japan over a 42-year period.

I taught English for 35 years, and I spent a year and a half at the University of Hawaii to get my master’s degree in the teaching of English as a second language. In Japan, I worked in movies, as you know. I also did Tokyo Disneyland recordings over there, announcements for the park for about 12 and a half years, the English announcements. I worked in movies, dubbed movies, dubbed TV programs, all kinds of stuff. I worked in movies, oh, about eight or 10 years, and then I kind of tapered off because I had a literary agency, I was teaching 25 hours a week, I was doing dubbing and recording Friday nights, Saturdays, and Sundays, we’d do five episodes a weekend of half-hour programs for kids.

While I was working in movies, I worked with Richard Widmark, Yul Brynner and George Chakiris in the movie Flight from Ashiya, which I have a copy of. I worked with Robert Mitchum and Brian Keith, making the movie The Yakuza. That was later, and I knew the publicity man (Hunton Downs), so he would take me down to Kyoto, and I kept taking stills for him, and then I got to work in the movie a little bit as a delegate to a conference. I’m not sure of the date of that.

Anyhow, coming back to the States, for the last couple of years, I have had an agent, and I worked on a TV commercial, and then also on the movie that I think I mentioned called Boy Culture, which was a Screen Actors Guild-sanctioned, low-budget movie. I think it cost only seven and a half million dollars, and I had a speaking part in that and got screen credit for the first time in my life. (laughs) It was shown at the Seattle International Film Festival, and it was shown before that at the Tribeca Film Festival in New York, and they said that there are people interested in distributing it, but it‘s a very specialized film because the basic theme is gay men, but it was very enjoyable; I was surprised! It was funny, the director did very well, and I thought very well of his work. Very nicely done, and we, my wife and I, saw the program in an audience, maybe I told you, that was 99.99% men of a certain persuasion mostly and very few women.

Anyhow, it was funny. I thought it was well done, and then when the director was brought up onstage, he invited those in the audience who had been in the movie, extras and speaking parts, up onstage, so I got to be in the spotlight a little bit. As I say, I enjoyed the movie very much, and I think it was well done. I didn’t embarrass him, I don’t think. I guess I gave a suitable performance. How good it was, well, that’s up to question. Anyhow, sorry, that’s a whole lot of detail there! Did that help you at all?

BH: Absolutely. Now talk a little bit about visiting the set of The Three Treasures because you wrote about that in one of your magazine articles.

CH: That was with Toshiro Mifune?

BH: Yes.

CH: It had monsters and things like that. I didn’t appear in that film, but I wrote about it. I believe I saw it, and of course that was Eiji Tsuburaya’s work with the different creatures and so forth. I did meet Toshiro Mifune and, through an interpreter, interviewed him one time, and then another time I saw him again, and I was able to hold the sword of the mighty Toshiro Mifune! (laughs) So I don’t know terribly much about the picture itself, but I included it in those pictures that were in the publication because I was able to get those from the studio publicity department. The one showing the two-page picture with King Kong, the guy in the gorilla suit, and Eiji Tsuburaya and his people, I took that picture. Where the negative is now, I don’t know, but it was spread across two pages because I walked in that day. I was able to go on those supposedly closed sets because I had interviewed him, and we kind of hit it off. I couldn’t speak Japanese, and he couldn’t speak English, but anyhow, I think I told you about the chair that was made out of a cardboard box. A big cardboard box that somebody had made for him, with sides (left intact) but a space (cut off the top and front) where they could put cushions. That was his special chair when he wanted to relax. I would go in there, into the set, and I would sit in it to the horror of the people around him! He’d turn around and wave. It was okay; I had the special privilege to sit in that chair.

Anyhow, I would watch him, and, you know, he’d see me, and so I could watch some of the things going on. So the two films that I have the best recollection of are King Kong vs. Godzilla, which I think is of particular interest to you, and Mothra, which I don’t know if you‘re interested in particularly.

BH: Oh, yes! Absolutely.

Chico Lourant during filming in the early 1960s. Photo © CliffEhnGee.

CH: Okay. What would you like to know about my recollections of King Kong vs. Godzilla?

BH: Well, you can talk about anything you remember, particularly working in the movie.

CH: Okay. I think I had been around the production because I was able to take that picture of Tokyo and the scene of the men working there, and the guy in the gorilla suit. I watched filming, too. This may have been reported elsewhere, but the fellow inside the suit, whose name I have somewhere, but I think you might have it, too, he kind of growled and everything to make his performance more realistic. (laughs) But he made sounds, of course, no sound was being recorded, and I watched them. He did stomp on things, but he had to do it correctly because it’s not easy to put them back together again if he made a mistake. But at any rate, it seemed to go okay.

Then I was called to go and work in that scene you have in the film. There was another fellow whose name I don’t think I ever heard, or I may have known his first name, but I didn’t know him. Other people I would work with frequently, or from time to time, and I kind of knew their names, but I didn’t know his. He had been hired to do a speaking part, and I had been hired just to be there beside him in the cockpit of the helicopter. I had no idea what the helicopter was like because all we had was our compartment mostly.

Anyhow, we worked and did what we were hired to do, and they told us to look below, but nobody put up a finger or did anything to get us to look in the same direction. So I think if you look at that film, you’ll see us kind of looking perhaps a little different direction than the other. Anyhow, the fellow did his lines, getting the mouth movement, and then we finished our film, our portion of it, and of course we could see nothing below us, but we were pointing down at what was happening with the iceberg below us. Then later, I got called to go back to do the voice for the fellow who was the pilot because he was working for the U.S. military and couldn’t come back that day. As I understood it, he was getting paid for the part, which means that he would get more money and include the recording of the voice. But I didn’t mind too much because I got to go and do his voice, speaking to the silent (person), me, visually. I’ve forgotten the exact words, but I think you recall what’s on the Japanese track. But I did his voice for the Japanese version of the film. Do you recall the words on that?

BH: I think, offhand, it’s something like, “What’s that, huh? Oh, it’s Godzilla!”

CH: It’s Gojira. I’m pretty sure of that because, although foreign people knew of it because of the Raymond Burr additions to Godzilla, which they called it, they knew that, and for Japanese people, it was Gojira. So I’m pretty sure I did say “Gojira” for the name of the monster. I don’t remember the words, but (they were something like,) “What’s that?” Then they look down at the iceberg, comes back to us, and that’s what I said, I don’t think we’re looking quite in the same direction because nobody put up an object for us to both look at, as I recall. Then the iceberg cracks open, and Godzilla comes out, which was filmed from some distance because he’s moving, and the monster stood at least, I think, close to six feet, something like that. It’s quite a ways down.

It looks to me like it was shot in the tank that was often used in scenes of boats and stuff in the pictures, the pictures in the publications were shot in the Toho tank. It had a background, and they’d fill it with water. It looks like it could have been done at night. I never knew what the helicopter looked like. I might have seen some of the movie, but I don’t recall seeing it in a theater. I was watching television a couple of years back. There was a TV documentary on movie monsters. For some reason, I turned it on. I think it was AMC.

I saw the submarine scene, and I recognized faces, and one was Johnny Yusef, also his real name is Osman, and he got screen credit, I believe. Osman Yusef (was in) the submarine scene, and there was another fellow in it.

BH: Harold Conway, maybe?

CH: Conway, yeah. I recognized him because I think I had worked with him once, and I knew of him, and I’d seen him around. He was in the submarine scene, and I said, “Oh, my golly!” I thought, “(If the) next scene is the helicopter, I’m in it.” And the next scene was the helicopter, and it had a number of windows, looking like you could have passengers in it. I didn’t know that when it was being made because all we had was the cockpit, more or less, and they filmed us, as you saw, close-up. It was Tohoscope, so it was widescreen. I didn’t know what was supposedly behind me. (laughs) I was seeing that for the first time, as I recall, at least in more recent years, the fact that there was more behind us, and the miniature was being filmed, supposedly we were up front and maybe the other people were supposed to be in back. I don’t know. Anyhow, I was thinking about Eiji Tsuburaya. Have you ever heard of the Japanese word sensei?

BH: Yes.

CH: Well, it’s difficult to translate, and it can mean “master” or “learned person” or something like (that). My wife even said “sir,” but it’s given to people of certain authority or responsibility over groups of people. So I think the word sensei could be applied to Eiji Tsuburaya, and watching him, as I recall, at work, he was the master of the group. His men all worked diligently, and they had great respect for him. I don’t recall him ever getting excited or anything like that, the way some Americans or European people might do. He was a very interesting guy, and he was very nice to me. One day I was able to write for the American Cinematographer magazine what I learned about him. Of course, I think his son took over those things in later years if I’m not mistaken.

BH: He took over Tsuburaya Productions.

CH: Yeah, I think so. Because then Eiji Tsuburaya was working for Toho Studios, it was my understanding, but later they must have started that company.

BH: Yes, he later started Tsuburaya Productions and did television. Well, you talked a little about Osman Yusef and Harold Conway, so I just wanted to have you share your memories of those two gentlemen as well as Robert Dunham.

CH: Well, Yusef was a very nice guy. And he would work in films, too, and I worked for him. I was living in the YMCA, which was a pre-World War II building. He would telephone in the evening or late afternoon and tell us where to go the next day. He was fair, and he spoke English very nicely. I think he spoke Japanese fluently because, I’m not sure, but I think he was born there. There was a Turkish community that lived in Japan and before World War II. They were Caucasian to the Japanese eyes, so some of them worked in movies.

(The) fellow who asked me when I first went to that studio when I was still in the army was a Turk also. He was the fellow who asked me (to) cooperate and fill in; he needed one more person. I guess somebody didn’t show up. But Yusef was a nice man; he’d call up and find the jobs, and they paid more money than a Filipino fellow whose wife was Japanese. I remember him only as Pedro. He’d pay 2,500 yen or 2,700 yen, but Johnny Yusef(’s company was) Kokusai Engisha Asenjo. Kokusai is “international.” I don’t know the translation of that name. But they paid more money, and if we could get around 3,000 or so yen, the YMCA hotel was 500 yen a day, breakfast was 100 yen, and then I would be out working or something, and eat at the commissary over at the studios or that kind of thing. You’d get lunch for 100 yen, and then in the evening I’d be out with my friends. One fellow was a British guy, Ron Self. He and I worked in movies together. I don’t know where he is today.

Now Conway I didn’t really know him, but he was there, and I recognized him, and I think I worked with him one time. You know the way you would film a car with a background of a screen?

BH: Right.

CH: And that was done in Hollywood a lot, and they had that at Toho. We did that, traveling in the car, and then we were filmed on location, so I got a couple of days’ work out of it. Another young guy who’d gone to the Antarctic with me on the whaling fleet was about high school age. I said, “Come on, we’re going to go see this movie.” He said, “Why?” “Oh, you’ll see.” And I had been cut out! They only had, I believe it was Conway, but one shot of a car going by, and he rushes out to look at it, as I recall. (laughs) My young friend said, “Why did we go to that movie?” “Well,” I said, “I was in that movie, but I was cut out of it!” (laughs) That’s what I thought had happened to me at Boy Culture that was made here. (laughs) But I wasn’t cut out! Anyhow, that brought back that little memory when I was cut out! But I got paid, of course. That was my main objective, but I liked to be around the cameramen because of my interest in movie photography. So Conway I didn’t know really, but Yusef, we talked sometimes, and he’d be working with us, and he would be out at the studio if there was a large crowd.

I worked a lot at Nikkatsu, and Daiei was somewhere down the street near the river, most studios were. Nikkatsu was built on rice paddies, and at least some of the soundstages had dirt floors. If they wanted to make a little pond or something, they would just dig down. I remember the Nikkatsu studios. I worked there quite a lot with my friend Ron Self from England because they were always filming Yujiro Ishihara movies.

He was a Nikkatsu star, and his brother was a writer who wrote books, and the books were made into movies, so he insisted that his brother, Yujiro Ishihara, be the star, and he was known for that. Shintaro Ishihara is the governor of Tokyo and has been for a long time, and he’s very well known politically, too. He’s still living, but Yujiro Ishihara, the actor, died in his 40s. I think it was lung cancer. But we worked on sets that were nightclubs and things that were in Yokohama because ships brought in a lot of foreigners to Yokohama, who would come ashore, and they could stay on the ship, but they could have entertainment and nightclubs and stuff. Some of the clubs were actually used, as I recall, during the day, and we’d be hired as extras to fill in among the Japanese.We’d be sitting at tables. Yujiro Ishihara sometimes, out at the studio, at supper he’d manage to get a bottle or two of beer, and then he wouldn’t be able to (act properly). As long as we got by six o’clock, we were on extra time, and we’d get paid, but sometimes we didn’t shoot because he wasn’t up to it! (laughs) And I remember that! (laughs)

Mr. Harrington speaks with Nikkatsu star Yujiro Ishihara in the early 1960s. Photo © CliffEhnGee

Oh, Bobby Dunham! I met him and worked with him, and we did a lot of talking and everything, and then I had (a) 35mm Arriflex camera because I had delusions of grandeur, and I wanted to make a movie. Anyhow, then I bought the camera from Birns and Sawyer, which is still in business in Hollywood, and I had my mother mail it to me at the army, but as I recall, it got there a little late, but I went back, and they let me take it, and I had my Arriflex camera, magazines, and battery holder, and everything. Then I bought a tripod from a guy who worked in Hong Kong, and he didn’t need the tripod for his camera, so I bought it from him. So I had tripod, camera, and then I acquired lights that were called polecats that you could raise up to the ceiling and attach lights to. So anyhow, I wanted to make a monster movie or at least a scary one, and if we got one hour or so or a little less even on film, we had a chance of selling it. So I went to Bob Dunham, and he wasn’t interested in that because he wanted to make a movie of his own idea. So that’s what became Time Travelers. So I kind of instigated it and got him going, and then he wrote the script, and he was the director, and he was the star, and Linda Purl’s mother was the female lead. I can’t remember her first name.

Linda Purl’s mother, Marshelline, who appears in Time Travelers. Photo © CliffEhnGee.

I think I mentioned that (Linda Purl) has appeared in over 20 movies for TV. That is kind of her specialty. She is also singing. I remember reading some years back, Rex Reed had reviewed her performance in maybe a nightclub, and then my friend Burr (Middleton), the movie actor, showed me a place where she sang for older people. Anyhow, she’s now I think starring, he told me, in a road company of Man of La Mancha. I thought it was going to come to Seattle, but I checked it out today, and it’s not. But I’d certainly like to see it and say hello.

Robert Dunham during the making of Time Travelers (1966). Photo © CliffEhnGee.

So anyhow, we were recording things for Bill Ross, but we were able to shoot because I was teaching at night, and Bob Dunham had lived in the house that we show in our movie, and we filmed it there in this house and on the streets of Tokyo early Sunday morning, about six o’clock, and there was very little traffic in the streets, so we were able to shoot the car scenes where Bob Dunham is driving around, looking for something in some kind of strange situation. If you look closely, you can see the reflection of a car passing by, but I didn’t notice it until about the fourth time I looked at the movie! (laughs)

Anyhow, we then went to report to the studio with Bill Ross to record at about nine o’clock, Sunday morning, because we did Friday night, all day Saturday, all day Sunday. So we went out and shot parts of our film because all it was was me and Bob. I had the camera, and he was driving the car. We did a number of scenes like that. I mean, go to work for Bill Ross and record all day into the evening, and we shot on other days. So we finally finished our movie. Bill Ross had some tapes of music and let us use those tapes. We hired a sound man, and we hired an editor, and Bob Dunham, he showed the places where he wanted the music, so we had it, more or less, professionally edited, and the music from the tapes was professional music that Bill Ross had had to record because there was no music on some movies that he was dubbing. So we had a production, and that was it! That was Linda Purl’s first movie.

I have a copy of the movie. Bob Dunham passed away a couple of years back. He was living in Florida, as you might know, and he had a stroke as I understand it and passed away. I used to go to his house in Tokyo, he had it in a certain location because nearby was the American school, and he figured that his kids would be able to go easily to the American school, but the American school moved. (laughs) So his kids weren’t able to go to that. I think his daughter did, I’m not sure. But that was way, way back.

On the set of Time Travelers. Photo © CliffEhnGee.

Anyhow, my friend Burr Hoyle had run into Linda Purl at nostalgia shows that are run in Hollywood. He was asked to go to them because of his grandfather. He’d talk about his grandfather and sell pictures of his grandfather (who played Ming the Merciless in the Flash Gordon serials from the 1930s). Then he began to have a record of his own, so he began selling his own things, and then he would go, I think, once a year to these shows and tell me about the people around him, names like John Agar and John Saxon, the guy who was in the Bruce Lee movie Enter the Dragon. He was there, various people, names I knew. Mickey Rooney and his wife, Richard Chamberlain, Howard Keel. Burr sent me pictures of him with these people. I’m dying to go down there and see one of these shows because some of the people, maybe one or two, I’ve actually worked with, I don’t know!

Linda Purl on the set of Time Travelers. Photo © CliffEhnGee.

Anyhow, Linda Purl had not seen the movie. I have a friend who runs a little studio — he’s a radio man — and I went to him because he had copying equipment. He copied the video of our movie, Time Travelers, and I sent it to my friend Burr. Then he passed it on to Linda Purl, and she was delighted. She had never seen the movie. Then of course her mother was there, the female star. I believe he said her mother and father are still living. They were in the social world in Tokyo, so Linda Purl grew up in a rather favored position. I wasn’t aware that she has an older sister who is in theatrics and that kind of thing, too. But anyhow, I was hoping she’d come to Seattle, so I could go and see her on the stage in Man of La Mancha, but I discovered today that maybe it’s not coming here, unfortunately. So that’s how she got the copy, and through my friend she sent her thanks that I could get it to her. I was happy to do it.

BH: So did you actually serve as the cinematographer on Time Travelers? Was that your duty on it?

CH: Oh, yes. Time Travelers was because I had the camera. I was going to make my own movie, and I asked Bob to star in it, but he wanted to do his own story. So he wrote the story, and then I went along with him. That became Time Travelers, but I instigated it because I had the 35mm movie camera. Some of the film I bought straight and others we got short rolls, you know, when you have a thousand-foot magazine, sometimes you don’t use all the film, but you keep the film and sell the ends. Of course, you had to be careful of the sensitivity of the film, what the rating was. Then one guy I knew who was still in the army, he managed to give me a few hundred-foot rolls of film, and I’d crank those into the magazine. So we were using 400-foot lengths, 150-, maybe 300-foot lengths, and maybe 100-foot lengths to make our movie. We had all kinds of ends and stuff. Sometimes we worked with 400 feet, but never a thousand. The Arriflex only held 400 feet.

Shooting Robert Dunham during the making of Time Travelers. Photo © CliffEhnGee.

BH: To change the subject, do you have any memories of working with Ishiro Honda?

CH: No, not particularly. I’m sure he was there to direct, but I don’t think he directed our little sequence in the helicopter scene. It could have been, but I don’t know because I was not aware particularly of the director in those movies because often, when I worked, I didn’t have a speaking part. In King Kong vs. Godzilla, I did not have a speaking part. But in effect, I did do recording because the other guy couldn’t make it back to the recording session.

Nikkatsu actress Reiko Sasamori in the early 1960s. Photo © CliffEhnGee.

(In Mothra,) there were the Ito sisters. I forgot their given names. If you look at the credits, you’ll see so-and-so Ito, so-and-so Ito, and “Jelly” Ito.

BH: (laughs)

CH: That’s Jerry Ito. And you know about him, I think.

BH: Yes, I do.

CH: His father was a choreographer on Broadway and a famous dancer. Jerry Ito was in, I think, the Flower Drum Song, I‘m not sure, but he appeared, and then he moved to Japan, and because of his father, he was known. He worked in movies. I think it was for the movie of the famous director, (Akira) Kurosawa. Kurosawa was looking for people to appear in the train scenes of a Mifune film where there was a kidnapping (High and Low). When there was smoke coming up from a factory, they switched to color because that was the signal to get the kid back, the kidnapped kid. Anyhow, Jerry Ito was at that audition. He might have gotten the speaking part or something somewhere because he was well-known, and he appeared, I think, in clubs, and he appeared in movies and had parts and everything. I ran into him occasionally, and I interviewed him one time. First, I took pictures of him at some place. He was doing some work, then I interviewed him by telephone later, but I already knew a lot about him at that time.

He was in (Mothra), of course. We were taken, or required to go out to Tachikawa, which was a U.S. Air Force base in the outskirts of the Tokyo area. We went into the military club (for) family, husbands, and wives and so forth. The two girls, the Peanuts, were there to attract attention of people in the club because the studio would give so much money for each person who would come out on the runway to appear in the movie as people in some foreign city. They would then use these Caucasians or Americans, and they would pay so much for each person who went out. The Peanuts were there to kind of encourage them to come out. Of course, they couldn’t speak English. I remember the club manager wanted to entertain them, so he was wondering what they would like. Well, they said, through an interpreter, I suppose, some ice cream. Of course, he gave each one a huge ice cream sundae. (laughs) They couldn’t finish it! They’d never eaten so much ice cream like that in their lives! (That was) the American way.

Then we went out, and not very many people came, so if you look at the scene, the still, showing the moth, and I think I have it in my magazine article, you will not see a crowd of people; you will see a line of people. So I appeared as an extra in that and got paid extra because I was brought out by the studio. That was a good idea for them, but it didn’t work out too well. So I suppose about 30 or 40 people did that, as I recall, something like that. Of course, I think I did go to see the movie, and the girls were singing a song, “Moth-u-ra, Moth-u-ra!” (laughs) I remember that! (Of) course, there’s no T-H in Japanese, as you might know. So it’s “Mosura.” But I think it was three three syllables because after consonants there is a vowel sound in Japanese. So it was three syllables — Mo-su-ra, Mo-su-ra — but in English, it’s Moth-ra, two syllables, as I recall. (laughs)

Robert Dunham appears in both Mothra and The Green Slime. Photo © CliffEhnGee.

I did work on other movies, but we never knew what we were working on because we were just there. The rest of it, I would just be an extra in those movies, although I did have speaking parts in other films, Toei, for example.

I did have something to do with the movie The Green Slime. We did some recording, and I might have appeared in it. Anyhow, we went to the set where it was being filmed. I think maybe Bob Dunham might have had a line or two or speaking part. I’m not sure. But anything I did would have been as an extra. I believe that was Toei. The monsters, little things, I never did see the movie, but there were little creatures. Have you seen the film, The Green Slime?

BH: Yes, I did see it.

CH: Do you remember the little creatures?

BH: Yes, that’s the kind of monsters that were in it.

CH: Okay. Now those were children that were hired to be inside those outfits. They didn’t hire midgets, although there are midgets and dwarves in Japan. But they just hired kids. I remember seeing that! (laughs) There were children in there, you know, eight or nine years old, something of that sort. They would be about, what, three and a half, four feet tall, maybe three and a half feet tall. So it was children inside those creatures that were around.

We dubbed a lot of that. (Robert Horton) was used to the Hollywood way of looping it, doing a small segment, looping it again and again and again, and only have a line or two of dialogue, whereas we were used to doing two or three pages of dialogue in dubbing! So we were able to do our dubbing, and that was no problem, we could (do) two pages of dialogue, we could go ahead and do it. But he wasn’t used to doing it that way. He had to have little portions, and then really concentrate on those. I think there was some comment from him, “How do you do that?” He was treated the Hollywood way, which is to dub cuts almost, I think. But we were doing scene after scene in dubbing TV programs and movies into English. Of course, the quality might not have been there. So I had something to do there, maybe I just went out to the set and watched them a while, but at least I did recording. I remember that. That was, to my recollection, Toei.

Chico Lourant during filming. Photo © CliffEhnGee.

BH: Did you do that with Bill Ross?

CH: Most likely, yes. I think so. Yeah, I think that was beyond the Johnny Yusef days because we had kind of a parting because there were different guys calling me up, and one time I said I could go, then I had to back out, and I didn’t realize it, but I was called to try out for a part, as I recall. He didn’t tell me exactly what he was doing, and there he is with his group, and there I am with the other guy, and he had called me first. I didn’t realize that he was taking people out for parts. I just thought it was extra, or the reverse, I’ve forgotten.

Anyhow, then he didn’t call me anymore, and I felt badly because I didn’t mean to deceive him. One guy had one thing, and one guy had a different thing, I understood, and one was a guarantee of some work, I think that was it, and the other was an audition. I needed the money, and I didn’t care about the audition. That was, I think, the controversy there. So from that point on, I didn’t work for Johnny Yusef. Then not too much later, I didn’t work in movies very much. But I had a speaking part, as I mentioned, (in) Flight from Ashiya, and my part is with Richard Widmark, and then my voice was dubbed because (they recorded sound on location, but the sound must not have been good). It was at the airport, and it may have been a conflict of sound or something.

So I went on from there, but I was always recording, and then I had to take a break because my wife — I wasn’t home for certain things on the weekends and then she got upset, understandably. So I had to withdraw from recording for a while. Finally, I said, “Look, if we need the money, I better go back to it,” so I went back to recording for Bill Ross. Also, there was another fellow named George Reed who did recording, too, and we worked for both of them. I think Flight from Ashiya was Bill Ross and Ed Keane. I’m pretty sure that was correct. The other movie, Robert Mitchum movie, that might have been Ed Keane, too, Bill Ross, getting people to work on it.

A cameraman’s job is never easy. Photo © CliffEhnGee.

BH: For my last question, I was just going to ask you about Bill Ross, and any memories of him.

CH: Well, he was always there. He was, I understand, one time I went to Shintoho, up the street from Toho, and I think the story there was there was labor unrest at Toho, and there was another studio up the street, and they were able to keep going up at Shintoho. If you check with Donald Richie’s books, I think that the U.S. Army tanks came toward Toho because the unions were pretty leftist and pretty strong! I think army tanks came to quell the excitement there.

Anyhow, by the time I got there, Bill Ross, as I remember, was under contract to Shintoho if I’m not mistaken. Anyhow, I ran into him perhaps there, and maybe I already knew of him because he worked, and I worked. Somehow, I’ve forgotten exactly when we met, but anyhow, then I got into recording for him. I worked and worked for him, and guys from the military radio worked for him. That was Burr Hoyle Middleton. Others could get off Friday nights, and Saturdays, and Sundays because Burr Hoyle, I remember, we used to go out in the fresh air in one place, and he would check with his radio because he would tape his show with records and everything. Then he could be (at) work Friday night, Saturday, and Sunday. So we would be recording like crazy, take a break, and maybe we weren’t needed; that’s how I got acquainted with Burr pretty well.

Bill Ross was always in the recording room where the board was and checking everything. His door often was open because he would be listening, but the door was open because there was no air-conditioning in those studios. We worked in all different places around town. I recorded, one place, in a closet for some people. They had equipment, but no room for the microphone and everything! So I recorded in a closet. That was another job I did somewhere, which wasn’t for the people that you have heard of. But I worked and worked on recordings and so forth.

So Bill Ross, we’ve been friends for, goodness, I think 40-some years. He’s been over there for a long, long time. He was there in the military, and his wife was a young actress, and she was in the movie Stopover Tokyo. I didn’t know which one she was, but I remember seeing it because there was kind of an introductory part, and then a guy said, because somebody’s passport (had trouble), “You must make stopover Tokyo.” On came the titles! She was in that movie.

When we worked in Kyoto, her family I think was down there, and her brother worked (on) The Yakuza because Bill Ross and I, he had a car, we were chosen to go out and pick up Jimmy Shigeta, who was brought in because — I think it was Tetsuro Tamba — couldn’t record properly to get the right breaks in the voice so that it could be re-recorded in English. So they kind of eased him out with some consideration and delicacy, and brought in Jimmy Shigeta to fill in, and we went out to the airport to pick him up. I got to go in and wait for him and bring him out. Then later, when he was in the makeup chair, and he was getting touched up here and there for makeup, then suddenly he (did) look like Jimmy Shigeta because at the airport we were a little confused because it was all Japanese faces. Bill Ross said, “You go in and get him.” He wasn’t sure. I said, “That’s him!” He said, “Why don’t you go?” It was him. We brought him back to the hotel, and he was worried about, the next day, having to do Japanese because his Japanese was a little rusty, but I think we reassured him. “No, there are other scenes until you get settled down, then you’ll have your lines.” That was The Yakuza.

An actor during the filming of The Yakuza (1974). Photo © CliffEhnGee.

My friend Eiji Okada was working in that. I had coached him in English for The Ugly American with Marlon Brando. He came to my first wedding, and I think I maybe mentioned it, in complete drag, you know, (haori hakama), formal kimono, men’s kimono, which had created a bit of a stir because people knew who he was. I said, “I’m getting married.” He said, “Oh, could I come?” Well, then he came! (laughs)

Always armed with a camera. Photo © CliffEhnGee.

He was a freelance actor. I think he passed away some years ago. I remember we were working at the International House, and across the street was a girls’ school, and I was teaching there at night. That’s why we met at the International House, and we went over and sat on the lawn behind the school building. He was looking across the valley, and there was Keio University. He was telling me about how he’d been a student over there years before because he was probably his 40s or something like that. This was a man who’s known internationally, and I was coaching him not as an actor, but coaching him with pronunciation and so forth, parts of his script, and things like that. Anyhow, so finally he came to my wedding and then he went on and did the movie with Marlon Brando. So he believed in that style of acting that Marlon Brando, of course, made famous.

Special thanks to Allan Murphy and FineLine Press for providing the photos (taken by Mr. Harrington during his time in Japan) that accompany this article.