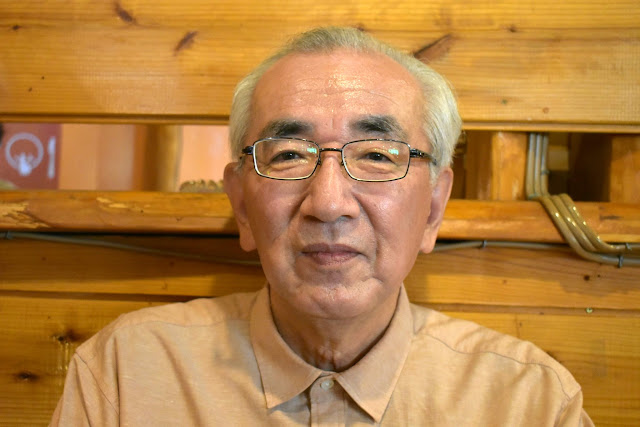

Born on May 9, 1950, Keiichi Sakurai grew up in Hokkaido and became enthralled by tokusatsu movies at a young age. He got his start in special effects as an assistant cameraman apprentice on the Toho TV series Zone Fighter (1973), which eventually led to numerous other Toho films, including Submersion of Japan (1973), Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla (1974), Zero Pilot (1976), Deathquake (1980), Sayonara Jupiter (1984), Godzilla vs. King Ghidorah (1991), Godzilla vs. Mothra (1992), Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla II (1993), Rebirth of Mothra III (1998), and Shin Godzilla (2016), on which Mr. Sakurai served as tokusatsu cinematographer (alongside Keizo Suzuki). In April 2022, Mr. Sakurai spoke to Brett Homenick about his decades-long journey to becoming a tokusatsu cinematographer in an interview translated by Maho Harada.

Brett Homenick: Please tell me about your early life, such as your hobbies and interests.

Keiichi Sakurai: As a boy, I was interested in toys and built [plastic] models. I liked handicrafts and often made things in elementary school.

BH: Did you watch tokusatsu movies when you were young?

KS: The first tokusatsu movie I saw was The Mysterians (1957) when I was seven years old. Back then, I had no idea what tokusatsu was or what was real or imaginary; I just thought it was an amazing movie. An older boy in my neighborhood said, “The tanks in that movie were this big,” and showed me the size with his hands.

I wondered why the tanks would be so small and didn’t understand what he was saying. I understood that they weren’t real, but I couldn’t grasp the concept of filming tokusatsu with miniature models. Anyway, The Mysterians was ingrained in my memory – it was a kind of trauma in a way. I’m in this line of work because I saw that movie. Back then, I was the same as any other kid and loved tokusatsu movies, so I went to see them often.

BH: How did you get interested in cameras and photography?

KS: I watched a lot of tokusatsu movies like The Mysterians and Varan the Unbelievable (1958) and wondered how they were filmed. I went to the library during lunchtime and looked up the word “movie” in the encyclopedia. Among the descriptions of how movies were made, it mentioned how tokusatsu movies were made. It even showed photos of airplanes hanging from wires. For me, wires were something that were very thick, so I wondered how they were able to erase such thick wires so they wouldn’t be visible on the screen. Was there such a thing as invisible wires?

The more I learned about these things, the more I wanted to make movies like that myself. I wanted to film in 8mm, but we didn’t have an 8mm camera. The only thing we had was a normal camera. Normal cameras were rare in those days, so kids weren’t allowed to use them. But I wanted to film in 8mm really badly. When I was in elementary school, I didn’t have enough money to buy an 8mm camera, so the best I could do was to imagine how I would film something.

When I was in junior high school, I got a part-time job so I could make my own money. I saved up and bought a used 8mm camera, and I bought film with my pocket money. During spring break after graduation, I could spend my time however I wanted, and my parents were lenient because I had already passed my high school entrance exams.

I got my friends together, and we made a kaiju movie. We made a kaiju costume and [miniature] houses. That was the beginning [of my career]. The movie was a black and white movie called “Daikaiju Rarugo.” When I watch it now, it looks shoddy, but it was a fun memory because I made it with my junior high friends.

I thought I’d have to study hard in high school. But, when I started high school, the kids whose desks were close to mine asked me what I’d done in junior high. I told them that I’d made a kaiju movie and showed them photos of the shoot. Everyone was interested and wanted to make one, too. So I made 8mm movies during my three years in high school, too.

BH: Did you go to college?

KS: Yes, I did. When I was in high school, I wrote a letter to director Eiji Tsuburaya. In the letter, I wrote, “Mr. Tsuburaya, when I grow up, I want to make kaiju movies, so I hope you can help me.” Mr. Tsuburaya wrote back and said, “If you want to work with me, I suggest you go to university before you join us.” So I decided to go to a university in Tokyo.

A year or two after I started university, Mr. Tsuburaya passed away. But, before he passed away, there was a tokusatsu movie called Battle of the Japan Sea (1969), and I visited the studio where they were using the Big Pool to recreate Sasebo Bay. All the staff members were veterans. To a 20-year-old student, they all looked like old guys. I was impressed by how professional everyone was and thought it would be very difficult for me to work with them.

I think it was the year after Battle of the Japan Sea that Mr. Tsuburaya passed away. After he passed away, I went to visit Toho Studios again, this time during the Godzilla. vs. the Smog Monster (1971) shoot. Return of Ultraman (1971-72) had been released at about the same time as Godzilla. vs. the Smog Monster.

At the time, Toho Bijutsu, which was part of Tsuburaya Productions, had subcontracted the Toho tokusatsu team to make six episodes of Return of Ultraman. Watching this shoot, I realized all the crew members were young. They were the same age as me or even younger than me. Before that, the crew making tokusatsu were all old guys, but now they were the same age as me. I thought, “Hey, even young guys can make tokusatsu movies. That means I can work in the tokusatsu industry, too!”

BH: How did you become a professional cameraman?

KS: I asked the crew how I could join the tokusatsu team. They said, “You could go to a photography school or film school.” So I thought, “All right, if I go to a photography school or film school, I might be able to join the filming team.”

I then went to see the tokusatsu section chief of Toho and asked him, “If I went to a photography school or film school, would I be accepted to join Toho?” He said, “Sure, if you graduate from a photography school or film school, you’ll have a good chance of being accepted.” So I quit university and went to a photography school.

At the time, there weren’t that many photography schools. I was already 20, and the program at Nihon University was four years, so that seemed like a risk. On the other hand, a school specializing in photography would only be two years, so I would graduate at the same age as if I continued going to university.

So I decided that it would be better for me to go to photography school. After I graduated, I went to see the tokusatsu section chief again. I told him that I’d graduated from photography school and asked if he could hire me, and he did!

BH: How did you join the TV series Zone Fighter (1973)?

KS: The first [project] I worked on after joining Toho was Zone Fighter.

BH: What work did you do on Zone Fighter?

KS: I started out as an assistant cameraman apprentice. Then I got an official contract – not as a full-time employee of Toho, but as a freelance crew member. My first job on Zone Fighter was to erase piano wires. I wondered, “Why does an assistant cameraman have to erase piano wires?”

When I joined the team, the crew gave me a present – a three-item, piano-wire-erasing kit! Toho had always erased the piano wires with three kinds of lacquer spray – white lacquer spray, black lacquer spray, and matting [de-glossing] lacquer spray. They handed me this kit and said, “This is your first present.” So, for Zone Fighter, all I did was erase piano wires.

In the latter half of the shoot, I was promoted from apprentice to official crew member and did things like adjust the focus. I learned different techniques for shooting tokusatsu scenes. During the shoot for Zone Fighter, the tokusatsu crew was split into two teams. I was assigned to the team that worked on the storm scene for The Human Revolution (1973), and we shot the scene of a storm at sea using the studio pool. I loved my job and loved working on such a large-scale shoot.

Zone Fighter was a TV show about a hero, so most of the scenes were fight scenes. I preferred the world of miniature models and shooting scenes in which models were destroyed. I wasn’t interested in fight scenes for a TV show about a hero fighting kaiju. They just looked like professional wrestlers. I liked it when it was just the hero without the kaiju, or just the kaiju without the hero, in scenes where they’re surrounded by buildings, and they’re interacting with people and society. But I wasn’t interested in the fight scenes because all you see is the action, and the scale isn’t very big, either. So I was very happy to work on the shoot of the stormy sea.

BH: Do you have any stories from the set of Zone Fighter?

KS: I had a hard time just keeping up with the shoot. It was one mistake after another. I don’t remember any particular stories from Zone Fighter. All I can say is that I made all the mistakes that an assistant cameraman apprentice is expected to make, like opening the camera lid without checking to see if there’s film inside. (laughs)

Luckily, the light in the darkroom was directly above me, so, when I opened the lid, the lid made a shadow over the film, and I immediately closed the lid. Because film in those days was wrapped very tightly, only the end was exposed to the light, so the film from the shoot wasn’t affected. I was saved! It’s something that everyone does at least once.

We often worked throughout the night during the shoot, so I was half asleep when I was changing the film. I had to turn the lights on and off in the darkroom to change the film, so I mistakenly turned the light on when I meant to turn it off. I left the unexposed film outside when I was supposed to take it into the darkroom. I made these kinds of mistakes, but there were no major disasters, luckily. Imagine if I had messed up the film for the entire day. I would have been fired on the spot! (laughs)

Otherwise, on Zone Fighter, I was constantly erasing piano wires. We would spray the piano wires to erase them, then diffuse them with lighting [as in softening the hardness of the wires]. But it was so hard! I almost gave up. Even if you spray a piano wire completely white, it looks black because, if there’s not enough light from the front side, you can see a silhouette on the piano wire, so it looks black. But, if you spray the piano wire too much, it gets thicker and becomes more visible. It took me a long time to learn the right technique.

BH: Which episodes of Zone Fighter did you work on?

KS: I think I joined from episode 5. The episode with Gigan was shot at the same time as The Human Revolution, so I didn’t work on that one. I rejoined Zone Fighter after the Gigan episode and continued until the last episode. The Ultraman Taro (1973-74) set was next to the Zone Fighter set. Zone Fighter was in [Stage] No. 3, and Ultraman Taro was in [Stage] No. 4.

When I carried the camera equipment from the camera storage area to the set in No. 3, I passed in front of No. 4. Sometimes, the doors would be open, and I could see the Ultraman Taro set, which was extravagant, with lots of high-rises. I was jealous. When I arrived at the Zone Fighter set at No. 3, it was just a field – just grass and mountains made with Styrofoam. There were hardly any miniatures. At the time, I’d never worked on a set with high-rises, so seeing the Ultraman Taro set made me want to work on a set with high-rises.

After Zone Fighter, I worked on Submersion of Japan (1973). It was so exciting because I finally got to work on a high-rise set! Submersion of Japan was an epic film with extravagant sets, so I got to taste the thrill of working on a Toho movie during the golden era. I’ve never seen such extravagant sets since that movie.

Next, I worked on Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla (1974), but I had a month or two before the shoot started, so they asked me to come “indoors,” which meant doing composite work. I was an optical printer assistant. I worked under Takeshi Miyanishi, who was the optical printer technician, doing things like aerial image mounting [as in mounting film on reels] and beam splitter mounting. There were different ways to mount the film depending on the type of film it was. I cleaned the film as I mounted it onto the Oxberry optical printer. That’s how I learned the composite techniques.

For this movie [Mechagodzilla], I just wanted to work on the tokusatsu. I wasn’t interested in the drama part at all, but I was told that I had to learn how to shoot human drama, too. So I was assigned to the drama part and went to Okinawa for the shoot. After the shoot for the drama part was over, I joined the tokusatsu team and shot the tokusatsu scenes.

The day I came back from Okinawa, there had been heavy snowfall in Tokyo. Because of the snow, I was late for the shoot. So I wasn’t there for the scene with Angilas. I arrived after the Angilas scene was done.

In this movie, Godzilla looked cute, so honestly I didn’t enjoy working on this Godzilla [movie]. When I look back on it now, I don’t think he looks cute, but that’s what I thought then. The first Godzilla I saw was King Kong vs. Godzilla (1962), and that was my image of Godzilla, with that scary-looking, upside-down-triangle face. But, in this movie, he was just bouncing around. It was the same for Zone Fighter. Godzilla joins forces with Zone [Fighter] and fights [alongside] him, but it wasn’t the image I had of Godzilla. Now I think Godzilla looks fine. Maybe I’m more laid-back now. (laughs) After Mechagodzilla, I worked on the Submersion of Japan (1974-75) TV series.

I think the Submersion of Japan [movie] shoot started about a month after Zone Fighter. I started working as an assistant cameraman on Submersion of Japan. The first shoot I worked on was the scene at the bottom of the ocean. The island sinks, the Wadatsumi [submarine] is launched, and it discovers patterns in the sand that look like a slug.

I remember having difficulty erasing the piano wires in this scene, too! The piano wires looked black against the bottom of the ocean, so we had to spray them white and diffuse them with lighting. I asked the lighting technicians to light the piano wires from the front with very weak lighting. I explained that, because the wires are sprayed white, they would appear gray with this lighting and become invisible. But the lighting technicians said they didn’t have any lights they could use for the piano wires. I remember having a very difficult time arguing with them about whether the piano wires were visible or not! (laughs)

After the scene at the bottom of the ocean, we shot the scene with the globe where they explain the theory about the Earth’s splitting up. After that, we shot the scene of the massive earthquake in Tokyo. For this scene, we had a huge area of high-rises, and there were lots of props. There was a miniature streetcar, which looked a lot like the streetcar they used in the Korakuen scene in King Kong vs. Godzilla.

There were cars that looked familiar, too, so they were probably from other shoots. It wasn’t just the miniatures – they also used some of the same artwork and horizons [backdrops]. I really enjoyed looking at these things. They used some of the same high-rises from [other] TV series, as well as high-rises that were made for this movie. So we were shooting on a huge set with tons of miniatures and props. It was the happiest moment of my life.

BH: Please talk about The Last Days of Planet Earth [a.k.a. Prophecies of Nostradamus (1974)].

KS: For Last Days, the tokusatsu was more sporadic. The nuclear plant explodes. The SST [jet] explodes. During one day of shooting, there would only be one or two tokusatsu scenes. We would arrive at 9:00 a.m. Of course, the [tokusatsu] art team would be decorating the set before we started, but the filming crew arrived at 9:00 a.m.

The explosion would take place at 3:00 p.m., and we would be done after that. That’s what our schedule was like. But I would have preferred to see more of a story take place before and after the explosion. For example, have more buildup to the explosion to explain why the explosion was going to happen. I think that would have been more interesting. Or, as another example, after the nuclear plant explodes, have radioactive winds pollute the air or something.

There was a director who wanted to shoot that kind of thing – an assistant director named Mr. [Koichi] Kawakita. In both the script and the storyboards, the nuclear plant explodes, and that was it. That’s all they had in the script. But Mr. Kawakita would say, “It’s only 3:00 p.m. We have until 5:00 p.m., so let’s shoot some radioactive smoke!” I think Mr. [Teruyoshi] Nakano was the [tokusatsu] director, and he said, “No, we don’t need that.” Mr. Kawakita had no choice but to step back. It was very much like him to want to shoot whatever we could shoot. Mr. Kawakita was hot-blooded back then. (laughs)

There was also the ocean of ice in Last Days. Oh, and there were the composite shots. There’s a flurry of shots: It’s snowing on the [Egyptian] pyramids, the roof of a farmhouse is ablaze with fire, and high-rises explode. [In the scene where the high-rises explode,] they placed debris on the ground and shot them against a black background so that they would fit the shape of actual buildings and blew the debris into the air with gunpowder.

The assistant cameraman who was at the shoot said that there was so much smoke that the blue sky immediately turned black the instant the gunpowder went off. There were only four or five shots in the explosion scene, so they could have just masked the pieces of debris and cut them out by hand. That way, they would have a shot with debris blowing up into a blue sky. That’s what I thought of back then, so I did that for the building explosions in Rebirth of Mothra III (1998).

There was a fire in Stage 7 during the Last Days shoot. In the scene, there was a forest that was dry, and the dry trees catch fire. The shoot wrapped just after noon, and the fire was put out. Because of the set we were using, we were in Stage 7 instead of Stages 8 or 9. Stage 7 was an old studio that had been used as a sound stage. And, in those days, tatami was used as sound insulation for the walls. Tatami is basically straw, and it was covered with slate.

The studio was very old, so the walls were worn out, and there were cracks in the slate. They used himuro cedar for the forest, which they dried so it would burn well. The sparks from the burning trees entered the cracks in the wall, and, like a futon fire, it smoldered very slowly. After a while, a fire broke out. The fire commotion started about an hour after the shoot had wrapped. We were taking out film and doing maintenance on our equipment when suddenly there was a blackout. We wondered what happened, and someone said, “No. 7 is on fire!”

Then all these fire trucks arrived – Toho Studios was full of fire trucks! The Toho Fire Station came first, but their fire truck was so small. (laughs) It’s funny to think of it now, although it wasn’t funny back then. Then the real fire trucks arrived, which were called Snorkel fire trucks, which had ladders could be extended by remote control.

They could do the firefighting by extending the ladders by remote control using cameras attached to the ladder. They were giving live commentary: “Right now, we are using remote Snorkel fire trucks to discharge water. However, it is taking longer than expected to extinguish the fire.” I remember watching this and thinking, “Who ever heard of live commentary during firefighting?” Now I can laugh about it as I tell you about it, but at the time it was quite dramatic.

BH: Please talk about what you remember from [Conflagration (1975)].

KS: We built a seven-meter tanker for this movie and did the shoot in the Big Pool. There was very little budget for movies at this time, so there wasn’t enough money to repaint the horizon [backdrop] behind the pool, which was a sky with clouds.

Until then, horizons were mainly used for commercials. Only parts of the horizon would be painted, like half of it, or one third. So, if we were to shoot the entire horizon, there would be dark clouds in the middle and a sunrise on the left side, for example. That’s why there are hardly any movies shot during this time that used the horizon behind the Big Pool. You would have a boat without the sky, for example.

For Conflagration, the sky was painted on only one third of the horizon. When the tanker sailed, it was only shot against the width of the painted sky. They didn’t paint the entire horizon behind the Big Pool until The Imperial Navy (1981). Until then, we had to use a dirty sky, basically.

In Conflagration, there’s a scene of an explosion of an industrial complex with gasoline storage tanks. I was in charge of the focusing for this scene, and we were on a crane above the burning tanks, which moved through the flames. We had to wear firefighting uniforms, but my hand had to be bare to do the focusing. As the crane approached the napalm explosions, which were going off in succession, blasts of heat from the napalm came rushing toward us.

We didn’t get any flames, just blasts of heat. It was so hot that all the hair on my fingers were burned off! I didn’t get burned, but I lost all the hair on my fingers. That’s how hot it was! It made me realize how dangerous napalm was. (laughs) Until then, I didn’t really feel anything during the filming of explosions. Sometimes, it got a bit hot, but that was it. But, during this shoot, I realized how dangerous it was.

BH: How did you get hired to work on Zero Pilot (1976)?

KS: I was on an annual contract with Toho, which was called Toho Eizo back then. At the time, I was working on most Toho movies, unless they overlapped with another movie I was working on.

This was the first movie directed by director Kawakita, so he was very excited. We did test shots of Zero fighter planes using radio control, U-cons [U-controlled planes], and rubber. I remember transporting a crane, 1/10-scale Zero fighters, and a full-size Zero fighter windscreen to an area that’s now called Tama Center. We did test shots of Zero fighter air combat scenes through the windscreen, from the perspective of the pilot.

We also went to Izu for a test shoot of the radio-controlled Zero fighters, but the wind was so strong. The radio-controlled Zero fighters had just been built, and the engines had never been used, so we were going to break them in during this test shoot. But the engines kept stalling mid-flight, and some fell into the sea. Some flew too high, so the radio waves from the remote controls couldn’t reach the Zero fighters, and they ended up flying far away.

We were able to shoot the air combat very well. But what’s difficult about shooting the air combat of radio-controlled planes is that you have to be quite close to them; otherwise, they won’t be in frame. With the naked eye, you can see the Zero fighter’s flying over here, and the [other] Zero fighter’s flying over there. But, if you frame the camera so that you shoot both of them at the same time, they just look like dots. And, if you do a close-up of one, the other one is out of frame. So for us cameramen it was a challenge.

We used 16mm [film] for the last scene where the Isshikirikko [bomber] is hit, and as it’s burning it ascends as high as it can. Then it does a somersault before it explodes. We used a 50mm lens with an anamorphic lens on a camera called Photo-Sonics. I think that scene was shot very well.

But, when we were watching the rushes, Mr. Kawakita got angry at Mr. [Motoyoshi] Tomioka, who was the cameraman. After the Isshikirikko [bomber] does a somersault, the camera pans as debris flies from the Isshikirikko. Mr. Tomioka continued to follow the debris after the explosion, but Mr. Kawakita was very angry because he thought Mr. Tomioka should have stopped panning at the moment of the explosion so that we could see the aftermath of the explosion. But Mr. Tomioka was filming at 10 times high speed, so it would have been impossible to stop panning when the explosion happened. Listening to their heated discussion in the staff room, I thought to myself, “It doesn’t really matter.” I guess I was still young at the time. (laughs)

We shot on a set with big Zero fighters. I don’t know what scale they were – maybe 1/3 or 1/4. They were about 2.5 meters, which would mean they were 1/4 scale. To create a sense of depth, there were 1/10-scale fighters behind the ones at 1/4 scale, and behind them were 1/20-scale fighters, then 1/50-scale fighters, and then 1/100-scale fighters. They were placed that way to create depth. When they flew in formation, the large ones had pitch, which meant that they generated wind when the motors were turned [on]. That meant that the wind would reach the smaller fighters in the back, which made them waver.

When we started shooting, the propellers were turning, and the wind made all the fighters in the back waver. We thought, “Oh, no! What should we do?” There was a special effects guy named Tadaaki Watanabe. He immediately ran onto the set and attached boards behind the propellers using black duct tape so that the boards wouldn’t be visible. By doing this, he eliminated the rotational pitch. In other words, he attached boards to the twisted propellers so that they wouldn’t generate wind when they turned.

Koji Matsumoto, the [wire operation] director, was a very impatient person, so he would yell, “Nabe! Get out of there! We won’t notice the difference!” But Mr. Nabe [Tadaaki Watanabe] didn’t budge and kept going until they all were fixed. Thanks to him, none of the fighters in the back wavered while the whole formation flew. I thought, “Mr. Watanabe is amazing. I respect him.” (laughs)

There was another interesting episode when we were shooting on location. In addition to radio-controlled planes, we used planes called U-cons. Before we had radio control, they attached two piano wires to the wings in a U-shape and made the fighter fly by twirling it around. That’s why they were called U-controlled planes, or U-cons. The U-cons flew in circles, so they were easy to shoot, so we used them for the air combat scenes.

The camera would shoot them from head-on or off to the side, following the U-cons. When we were shooting two of them, we needed them to be as close as possible. One time, they got too close and rammed into each other. Both of them broke into pieces. I was a camera assistant at the time, and I was on the camera that was right beneath them. Because I was in charge of the focus, I was right next to the lens, and the cameraman was behind me. And behind the cameraman was the third [assistant].

When the fighters crashed into each other, the engine-driven propellers, which were basically lumps of metal, came crashing down toward us while the propellers were turning. I thought, “Oh, no! It’s coming directly toward me!” The cameraman was fine because he could use the camera to shield himself. The third [assistant] could use the cameraman as a shield, so he was fine, too. That meant that I was in the most dangerous spot.

When the engine-driven propellers came crashing toward me, I ran away. (laughs) Well, I couldn’t run, so I kind of twisted my body. When I twisted my body, the engines went in a completely different direction. Everyone was very cold toward me and said, “What kind of guy are you? You didn’t think of protecting the others.” But, if that engine had hit me, I would have died! (laughs)

In those days, Mr. Kawakita had a lot of things he wanted to do. He was a bit reckless. But there was a good ambience during the shoots. We were able to shoot everything we wanted to shoot, and we made a very interesting movie.

BH: What about The War in Space (1977)?

KS: As you know, this was a movie that we wanted to get out before Star Wars (1977) came out [in Japan]. Some crew members had gone to the U.S. to see Star Wars, and they came back with some 8mm film to use as a reference. Everyone was saying how amazing it was, so I was curious. The image I had of space movies was 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), so I wondered if Star Wars was even better than 2001: A Space Odyssey. But, when I saw it [Star Wars], I didn’t think the effects were that great. I thought that 2001: A Space Odyssey was much better. I think most of the filming crew back then felt the same way.

So we started shooting The War in Space. In this movie, outer space was blue. I thought, “Not another blue outer space! Isn’t space supposed to be black?” But I guess, when you use blue as the color for outer space, the wires are easier to remove. And the audience isn’t used to space being black. But I thought, “Isn’t it outdated to make movies where outer space is blue?” That’s what I thought, but I was young back then.

The Gohten had a drill. Its tip was roundish, and the back was squarish. When it spews out the Space Fighters, it turns into a revolver. It was supposed to be realistic, but it seemed more like a space opera. If it was going to be a space opera, there could have been more drama to the story. The actual drama side was a bit dark, wasn’t it? Again, I was young, so that’s what I thought back then. When I see it now, I think it’s interesting as it is.

The piano wires were a problem in this movie, too. Both the Gohten and the Daimakan were huge and heavy. We had to use three piano wires for the Gohten, and four piano wires for the Daimakan. We used thick piano wires – they were more like cylinders, actually. If they were lit from the right, the right side [of the wires] looked white, but the left side looked black because it was in shadow. No matter how white we painted the wires, it made no difference. We just couldn’t make the piano wires disappear.

So we said to Mr. Matsumoto, who was hanging the warships by piano wire, “No matter what we do, we can’t make the wires disappear. If we use thinner wire, we could make the wires disappear. Is there any way we could use thinner piano wire and just use more wires?” He said, “If we use thin piano wire, and one of them breaks, they all will break.” And we thought, “Right, of course.”

But he said, “I’ll show you. I’ll use thin piano wire, and they all will break. Just watch.” He changed the piano wires to thinner ones and then started pushing down on the warship. He said, “Watch carefully because these thin piano wires are going to break.” But they didn’t break. So he kept pushing down on the warship, and he pushed even harder. Eventually, he was pushing with all his might, and the warship actually fell. Then the [tokusatsu] art team became furious. They said, “Matchan! That’s enough!” (laughs)

At the time, what troubled the filming crew most was the piano wires. We just couldn’t make the wires disappear. Nowadays, in digitalizing these old movies, they’re debating whether they should erase the wires or not. I think they should erase them because they shouldn’t be visible.

With film, the brightness was adjusted during the final stage. For example, if the screen is too white because there was too much dust, we would burn the film a bit so that the brightness matches the film before and after the shot. If we had made the film a bit darker, sometimes the piano wires became more visible. If this was the case, it would be better to have the shot be brighter rather than have the piano wires visible.

With digital, you can adjust many more things like the contrast. In digital, if you adjust the contrast, color, or brightness, sometimes the piano wires become more visible than they were in film. There is a risk that color correction will be done without considering that the piano wires would become visible.

Whenever I watch an old movie that’s been digitalized where they’ve intentionally left the piano wires visible, I get frustrated because I know that we adjusted that shot to be brighter so we wouldn’t see the piano wires, or this shot was darker.

There was something called rushes, which were film that was developed as soon as it was shot and printed without any processing. During the editing process, they sometimes had two rolls of film. If one roll was brighter than the other, the exposure of one of the rolls would have to be adjusted, so they would burn it a bit. When they did this, sometimes the piano wires became very prominent. This happened in Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla.

During the close-up shot in this scene when Godzilla is magnetized and pulls [the flying] Mechagodzilla toward him, there were piano wires that we couldn’t see in the rushes. But, when we adjusted the brightness in the print, the piano wires became visible, so we undid the adjustment to the original brightness so the piano wires wouldn’t be visible.

This happened even with film, so, whether you’re converting it onto video or digitalizing it, you have to be careful and check things like gradation and the details, like the piano wires. So, if they’re digitalizing these movies, and the wires become apparent, it’s not because the resolution is better! They shouldn’t leave the piano wires in. Those wires are not meant to be seen, so please erase them!

BH: What was working with director Nakano like?

KS: Director Nakano worked at Toho, then for Mr. Tsuburaya. He was Mr. Tsuburaya’s assistant director for many years. Whenever he got drunk, Mr. Nakano would always say, “You should never be an assistant director for eight years! Everyone thinks I’m an idiot for being an assistant director for eight years.” Mr. Nakano often said he wanted to make comedies. When Mr. Nakano started directing, he had to work with very small budgets, which meant that he faced a lot of difficulties. He had a hard time trying to make things work on such tight budgets and very little time. Back then, I was young, so I questioned the way he did things. But now I look back on it and think about how hard it must have been for him.

He constantly strives to make his work different from Mr. Tsuburaya’s. He also tends to include Japanese culture, like Noh. His colors tend to be more Japanese, as well. He has a unique style. Sometimes, I had trouble understanding what he wanted. (laughs) But he’s a very good man.

During The War in Space, there were three different sizes of the Hell Fighters. The small Hell Fighters, which were about five centimeters, were originally supposed to have light bulbs inside them. But, when it arrived [on the set], it was a solid piece of plastic, so we couldn’t place light bulbs inside them. The art team suggested we attach light bulbs to the outside with paper tape. Mr. Nakano said, “I guess that’s what we’ll have to do.” Seeing that, Mr. Kawakita said, “Director Nakano is so nice. If it were me, I would get mad!”

BH: What about Deathquake (1980)?

KS: On Deathquake, there was the destruction of a high-rise building and the subway. There was also a plane crash because the ground cracks open when the plane is about to land. We used miniatures and a system called front projection to shoot the scene of the plane’s crashing into the maintenance hangar when it was about to land. We took the film that had been shot and projected it, and we had black smoke rising in front of the projection to create atmosphere.

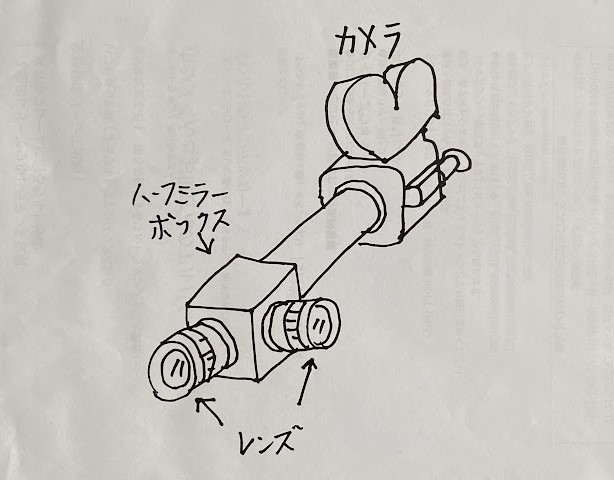

Sometimes, we had actors act in front of the projection. Mr. Nakano was very good at that kind of thing. The front projection system started being used for tokusatsu scenes in Zero Pilot. We also had trouble erasing the wires for that film. Anyway, the front projection system was revolutionary at the time. We had equipment for the front projection system before then, but it was too big and difficult to maneuver. Then we got new front projection equipment that was easy to maneuver, so we started using it because it was easier to use. Mr. Kawakita’s Sayonara Jupiter (1984) was the first movie to use the front projection system, which was easier to maneuver.

BH: What was your work on Sayonara Jupiter?

KS: For Sayonara Jupiter, I was the head camera assistant. I was also in charge of the B-camera. We used a Snorkel Camera for this film. While Mr. [Kenichi] Eguchi and Mr. Kawakita were shooting, I was in the corner of the set with a Snorkel Camera. They gave me a spaceship and told me to take random shots of it. So I shot the spaceship with the Snorkel Camera, taking shots sliding off the body, and rotating around the gravity generator. All day, I was by myself in the corner of the set doing this. Continuing with what I was saying about front projection, Mr. Kawakita liked what we called “cut screen.”

Basically, we placed a smaller screen in front of the main front projection screen and had miniatures on sticks sticking out from the smaller screen in such a way that the sticks couldn’t be seen from the camera. We also hid the mechanics behind this smaller screen, which was sometimes set on a dolly, which allowed us to move it around. Mr. Kawakita liked using this cut screen system. We used this system to shoot the Mars scene at the beginning of Sayonara Jupiter. That was also novel and fun. We also used a “biphenomenal” lens in Sayonara Jupiter, which has two lenses with different focal lengths. We used this lens to shoot the cockpit and the miniatures at the same time.

Sayonara Jupiter was a space movie that Mr. Kawakita did after he did Zero Pilot, so he put even more effort into the composite shots for this film. This time, outer space was black, not blue. Most of the scenes didn’t use piano wires to suspend the spaceships, and the stars had to be put in with composite shots. Mr. Kawakita’s biggest concern was whether he should use a blue background to put in the stars with composite shots, or if he should use another technique. Back then, we did a lot of tests, but it was hard to remove the blue background cleanly.

We tried using fluorescent lights and the transparent light method [tokakoshiki], but we couldn’t remove the blue background very cleanly. In the end, Mr. Kawakita decided to use the black-and-white method and the shape-masking method. Using these methods, we were able to remove the blue background very cleanly, and the stars looked real. For the stars, Mr. Kawakita got us to try all sorts of things, including high-contrast film, which isn’t easy to use because it has very little latitude. But it was really interesting to try all sorts of different things.

BH: What was your relation like with special effects director Koichi Kawakita?

KS: Both Mr. Kawakita and I shared a love for The Mysterians. I watched it when I was in the first grade, and Mr. Kawakita watched it when he was in junior high school. Despite the difference in our age – we were eight years apart – we both fell in love with tokusatsu through The Mysterians. When I started [at Toho], Mr. Kawakita often took me out for drinks, and we also had drinks in the staff room. All Mr. Kawakita ever talked about was tokusatsu. I loved these discussions and learned a lot from them.

He always talked about special effects techniques, like blue background composite shots, what “separating” meant, or how we would do a specific composite shot. He often talked about composite shots. It was really interesting to hear him talk about these things, and I learned so much from him. But we were young, so we were quite reckless! (laughs)

We would finish at 5:00 p.m., and I would say to myself, “I should go home and do laundry because I haven’t done laundry in a while.” Then Mr. Kawakita would be at the back entrance of the studio. I tried to avoid eye contact with him because I knew he would ask me to go out with him. He would say, “Come with me,” and I would have to go drinking with him until the last train. Looking back on it, these are wonderful memories.

BH: Do you have any [other] memories from the production of Sayonara Jupiter?

KS: One of the highlights of Sayonara Jupiter was rebuilding the industrial motion control [system] so it was usable. At the time, using computers was rare, and I didn’t know anything about computers. I didn’t even know what the Enter key was! (laughs) I had no idea how to input the settings for the motion control [system] using a computer. One time, I had put in the settings, but none of the settings had been saved. Back then, there were no safety mechanisms on motion control devices. When the camera turned around, the arm of the motion control moved with so much force that it crushed the motor of the camera! I couldn’t believe how strong it was. I realized then that I needed to learn how to use computers; otherwise, I wouldn’t be able to keep up with the times.

BH: Please talk about Kenichi Eguchi.

KS: Mr. Eguchi joined Toho from Tsuburaya Productions around the time of Last Days. I heard that he came to Toho because he quit Tsuburaya Productions after a dispute about piano wires. Mr. Eguchi graduated from a railroad school, so we were curious why he wasn’t working for a railroad company. When we asked him, he said, “I attended railroad school because I wanted to drive steam locomotives. But they stopped using steam locomotives, so I quit because it was meaningless for me.” When I heard that story, I remember thinking, “What an amazing person!”

I have more stories about Mr. Eguchi, but he’s still alive, so I can’t say anything bad about him! (laughs) That was the kind of person Mr. Eguchi was. Just like when he quit the railroad company because they stopped using steam locomotives, when he quit tokusatsu, he said, “If they’re not going to make tokusatsu movies anymore, I’m going to quit.” He’s a farmer now. When he quit tokusatsu, he threw away all his tokusatsu equipment and anything that had to do with tokusatsu. If he gets asked for an interview about tokusatsu, he refuses. That’s the kind of person he is. So I can’t really say anything about him.

BH: Did you meet Sakyo Komatsu? What was he like?

KS: I saw Mr. Komatsu because he came to the set often, but I never was very close to him. The only time I spoke to him was not on the set, but at the Tanegashima [Space] Center. I was there to film a rocket launch. Mr. Komatsu was there for a different project, but had also come to see the launch. I knew of Mr. Komatsu, but he didn’t know me. I went up to him to say hello. I said, “It was a pleasure working with you on Sayonara Jupiter. I’m Sakurai from the tokusatsu team.” I happened to be wearing a Godzilla T-shirt, and he said, “That’s a great shirt. Give it to me.” I said, “I’m sorry, but this is the only T-shirt I brought with me.” That was the only conversation I had with him. (laughs)

BH: How did Mr. Komatsu and director Koji Hashimoto work together?

KS: That involves the drama side, so I have no idea.

BH: How did you get hired to work on Godzilla vs. King Ghidorah (1991)?

KS: I was asked to join part way through the shoot. At Toho Studios, there’s a place for landscaping where they have lots of trees planted, which they use for shoots. If they need a tree, they dig it up. That’s where the scene with Godzillasaurus was shot. I was in the office, and they asked me to go to the shoot and help. That was how I joined Godzilla vs. King Ghidorah.

BH: What [else] do you remember about filming Godzilla vs. King Ghidorah?

KS: I helped out on the shoot and also drew storyboards. There were three people drawing storyboards: Ryu Hariken [Hurricane Ryu], Mr. [Kunio] Aoi, and me. We were told to go to a back room, and they gave us the script and told the three of us to draw the storyboards. At first, I wasn’t sure why they asked me to draw the storyboards. But I thought about it and understood it was because I had experience working on shoots, while the other two didn’t. So I could tell them if what they had drawn would be possible to shoot or not.

I was in charge of drawing the storyboards of the scenes where Godzilla appeared alone. The other two drew the storyboards of the fight scenes. The director would look at the storyboards and say, “That’s interesting; we can use that.” He would take out a pair of scissors and cut out the scenes he liked, and we would have to reorganize the rest.

When the shoot started, Mr. Eguchi and Mr. [Toshimitsu] Oneda were the cameramen. I was the third cameraman and shot whatever the other two were unable to shoot. I also shot some minor shots on my own in the corner of the studio. For the fight scenes and the major scenes, they needed three cameras, so I would also shoot [those scenes].

For King Ghidorah, the shoot never seemed to end. We couldn’t build big sets because of budget constraints, but we also had to finish the shoot by a specific date. But, after the shoot, there were still shots that hadn’t been shot. So Mr. Eguchi, who was an employee, myself, and one or two assistant directors stayed on and shot the remaining shots. We shot scenes like KIDS’ turning around and flying away and close-up shots.

At the time, Toho was closed during the Obon holiday. We went to the deserted studio and asked the guard in the special effects art team to open the studio door for us. We took out all the equipment like bicycles for rotation and dollies. Because it was during the Obon holiday, they didn’t even turn the air conditioning on. So we went to the camera maintenance room, which was a small room, where we hung a black backdrop and set up the contraption in front of the backdrop.

Just when I thought we were done, we were told to go to the Tokyo Laboratory to help out with the composite shots. So Mr. Eguchi, myself, and the assistant director went to the Tokyo Laboratory and helped with mask-cutting for the composite shots. I did the mask-cutting of the Atomic Bomb Dome [in Hiroshima] for the scene where King Ghidorah flies in and the grassy hill in the scene where Godzillasaurus leaves.

Mr. Kawakita did the animation for the last scene of the red beam emitted towards the camera. He wanted a sharp beam like in Star Wars, but there were too many frames, so it ended up looking a bit elongated. So I even helped out with the mask-cutting! For this movie, I got to work on many aspects of movie-making – I drew storyboards, did the shooting, and worked on composite shots. I learned a lot, so I have a lot of good memories about this movie.

BH: Please talk about working with Mr. Eguchi and Toshimitsu Oneda.

KS: Mr. Eguchi did the wide shots, and Mr. Oneda shot the closeups. That’s how they divided the work between the two of them. Mr. Eguchi shot the really wide shots, and Mr. Oneda shot the closeups using a telephoto lens. If Mr. Oneda wasn’t able to use a telephoto lens for the closeups, he would hide his camera between the buildings on the set, or wherever he couldn’t be seen from the other camera, and shoot from there.

Mr. Eguchi’s shots, which were generally the wide shots, served as the basis for the movie. From these shots, you understood what Godzilla and [King] Ghidorah were doing and the situation they were in, and Mr. Oneda’s shots supplemented Mr. Eguchi’s shots. I operated the third camera and took supplementary shots. So my job was to provide shots from unusual angles and other shots that hadn’t been taken.

In comparison to Mr. Eguchi’s wide shots, Mr. Oneda’s shots were taken with a telephoto lens, so they had a unique style. If he were using a 250mm lens, for example, he would compose his shot within the 250mm frame. He almost had to penetrate the set and go beyond it to make his composition, which gave the impression that they were compressed. Mr. Eguchi was great at taking action shots.

Around the time that Mr. Kawakita shot Godzilla vs. King Ghidorah, he liked to shake the camera, like he did in Godzilla vs. Biollante (1989). He thought that it made the scene even more impressive. So we made a shaking stand that we used to shake the camera whenever Godzilla or another kaiju fell. But it was really hard to get the timing of the shaking right! It was especially hard for Mr. Eguchi’s wide shots because he was shooting with a full frame. If he shot too tightly, the camera would lose sight of the kaiju during the shaking, so it was really difficult.

BH: What do you remember about filming Godzilla vs. Mothra (1992)?

KS: Like for Godzilla vs. King Ghidorah, I also had to draw the storyboards for Godzilla vs. Mothra. I worked with the same people. For King Ghidorah, we didn’t have enough time, but, for Godzilla vs. Mothra, we started working on the storyboards a bit earlier. For the scene of the destruction of the Nagoya Castle, I wanted to include both the destruction of the miniature and the actors in the same frame, so I drew the storyboards so that there would be a composite shot of the miniature and the actors in the same frame.

It didn’t have to be super accurate because it was a shot of the destruction of the miniature, so I wrote in the storyboard that the miniature didn’t have to be perfect. But the art team made the miniature perfectly! All we needed was a shot of the castle falling apart, and we were going to add composite shots to it. I got someone to make a mask for the castle that was falling apart by hand, and we were able to depict pieces of rubble falling onto some actors. I don’t remember which ones, but I drew the storyboards for two or three other shots where I used similar tricks.

You know the scene where Mothra’s egg hatches on a cargo ship, and the cargo ship gets attacked by Godzilla? The egg hatches, and the Mothra larva crawls out of the shell. I shot that scene with a separate team in the corner of the studio while the director was filming the main shoot. We debated how Mothra’s egg should hatch, and how fast the egg should crack open. We decided that it should hatch like the original Mothra and burst open.

Mr. [Masahiko] Shiraishi agreed that we should do it that way, so we decided to start the shoot. Just as we started shooting, the director came over, and saw the egg burst open. He said, “What was that?” So I said, “We thought the Mothra egg should burst open.” He said, “That’s not the image I had. I imagined Mothra’s egg would crack open before the larva crawls out.” I said, “Why didn’t you tell us before we started?” He smiled bitterly and said, “Forget it! I give up.” (laughs)

I also shot the scene with the Maser weapons, which I shot with the props team. We shot the helicopters’ banking and shook the camera. We thought it would be boring if the helicopters just flew straight, so we decided that it would look cool if we shot them while they were banking. Then the director came over and said, “Why are you always shaking the camera whenever you shoot the helicopters?” He used that shot, anyway. (laughs)

BH: What do you remember about filming Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla II (1993)?

KS: For Mechagodzilla, the overall structure was pretty much the same. By this time, I wasn’t drawing storyboards anymore and was mainly working on the shoots. The shoots were done in the same format, with me in the corner of the studio, shooting scenes like the one at the dock where Mechagodzilla is being welded, and sparks are flying.

The strongest memory I have of Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla II is shooting nonstop for 35 hours on the last day of the shoot. On the last day, the first team was shooting at the Big Pool. It was summer, so it was tiring to do anything. We were filming from above, so we had to lay the rails above the set.

We had to move all the equipment and the rails to a place that was 11 meters above the ground, which was about three stories high. We were coming and going many times to move the equipment, so we were all exhausted. It took us all day, so we thought they would call it a day. But it was the last day, and they started the shoot. We were shooting all kinds of shots for the composite shots.

When morning came, we thought, “It’s morning, so they have to stop.” But they kept going. Mr. Eguchi’s team and Mr. Oneda’s team were shooting, and I was on the open set shooting the scene of the laboratory’s being destroyed. Finally, after 36 hours, the shoot was over. But, on the positive side, we didn’t have to continue shooting afterward like we did for King Ghidorah. That has nothing to do with the actual shoot, but that’s my strongest memory of Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla II.

In terms of the actual shoot, I shot the scene where Rodan comes to Tokyo and picks up the freight container. We shot the scene of Rodan’s destroying a bridge of the Yurikamome monorail track. We set up a miniature of a portion of the bridge in front of the backdrop and shot Rodan’s destroying the bridge. The backdrop was a photo of Odaiba, which we photographed ourselves. Odaiba was still under construction, and the area by the sea was all private property, so we couldn’t go near the sea to get a good shot.

We had to ask for permission to take photos, but we went at the last minute, so we were refused permission everywhere we asked. But, finally, we found a warehouse that allowed us take photos, and we took photos from the top of the warehouse. We finally got the right shot, which was enlarged and served as the backdrop. We set up the miniature of the bridge in front of this photo and shot the scene of Rodan’s destroying the bridge. So, in addition to creating the set, we had to prepare all kinds of materials ourselves, like the photo for the backdrop.

We also did aerial photography for Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla II. We used a white background because we were going to add in the shadow [of the kaiju] to the aerial photography with composite shots. I remember using a lot of different tricks like that for this movie. Nowadays, it’s easy to add in a shadow with computer graphics. But back then it was much more difficult. We had a lot of trouble trying to make the shadow change shape when it was flying over buildings.

BH: Did director Kawakita change over time?

KS: Yes, he changed quite a bit. When he was young, he established himself as a director very quickly. But, gradually, he started incorporating elements as a producer. In the latter half of his career, he attached importance to creating a structure with each movie he made and became more involved in the planning stage as a producer.

But what didn’t change is that, on top of being a producer, he still wanted to direct. And he rarely left anything up to others. I often thought that he should entrust some of the work to the younger generation, but he always insisted on doing things himself. In the latter half of his career, he started his own company and became the president. He could have focused on being the president, but he still wanted to direct. I guess he loved directing and shooting movies. Thinking back on it, I think he should have handed over the reins to the younger generation.

BH: What are some of your [other] memories of director Kawakita?

KS: There’s too many. There are ones I can talk about, and others I can’t. (laughs) I’ve mentioned quite a few already. In the latter half of his career, Mr. Kawakita started his own company. He was going to make a new TV series called [Chouseishin] Gransazer (2003-04) and invited me to join the crew.

A lot of things happened around then, but, in short, I quit Toho Eizo Bijutsu, became independent, and worked on Gransazer with Mr. Kawakita. That’s when I thought he should hand over the reins to the younger generation. It was understandable that he was still directing the first year after he had started his company, but from the second year onward he could have let someone younger direct.

After work, we often gathered in director Kawakita’s staff room. Under the pretense of reviewing our work, we would hold drinking parties, which were a lot of fun. If Mr. Kawakita was in a bad mood, we would all be relieved when he left. We would jokingly say, “The Kawakita team is best without Mr. Kawakita.” (laughs) Mr. Kawakita often got worked up, so it was difficult.

BH: Why didn’t you work on Godzilla vs. SpaceGodzilla (1994) or Godzilla vs. Destoroyah (1995)?

KS: I had other work during this time. I wanted to work on these movies, but I think Mr. Kawakita wanted to change the staff. I’m not really sure why I didn’t work on these movies.

BH: What did you learn about filming tokusatsu in the Godzilla series in the 1990s?

KS: In the 1990s, the tokusatsu staff were all very young and not very experienced. But, with each movie – Godzilla 1985 (1984), Biollante, King Ghidorah, Mothra, Mechagodzilla – we gained more experience. We matured and improved our skills. I think you can say that the Godzilla series helped develop the tokusatsu staff.

BH: How did you get hired to work on Rebirth of Mothra III (1998)?

KS: Rebirth of Mothra III was the first tokusatsu movie directed by [tokusatsu] director Kenji Suzuki, and he invited me to join the crew. I hadn’t worked on a movie in a while, so I was able to do a lot of things I had wanted to do, like the destruction of the city of Nagoya and the collapse of Nagoya [TV] Tower. For the collapse of Nagoya [TV] Tower, we went to the warehouse and found the top of Nagoya [TV] Tower left over from the scene in [Godzilla] vs. Mothra where Battra destroys it. So we decided to use it.

In the movie, we incorporated a scene where the top of Nagoya [TV] Tower gets bent. I went location scouting in Nagoya and drew a detailed storyboard for this scene. There was also a scene where a new tower building in front of Nagoya Station gets destroyed. Around this time, the Mothra series didn’t have much of a budget compared to the Godzilla series, so we couldn’t build miniatures.

I decided to get around this by building plaster models and adding composite shots over the plaster models to create scenes of buildings’ collapsing. I liked the effect of adding composite shots over white models. So I drew the storyboards for these scenes and shot them. I was grateful that director Suzuki let me do what I wanted.

BH: You and Mr. Eguchi worked together as tokusatsu cameramen on Rebirth of Mothra III. Please talk about this experience.

KS: It was like all the other movies we did together. I don’t think there was anything different in this movie. As usual, Mr. Eguchi took the main shots, and I took the shots for the composite shots, like the destruction of the city of Nagoya. I came up with ideas of how we could shoot these shots, drew the storyboards, and shot them. For Rebirth of Mothra III, I also did the aerial photography, shooting over a sea of trees and shots like that for the composite shots.

It was a lot of work to do the aerial photography. Director Suzuki asked me to take photos for the backdrops of the air combat scene between Mothra and [King] Ghidorah. My notebook was full of all the shots I needed to shoot: looking down from the top, looking up from the bottom, attaching the camera to Mothra, ascending rapidly, etc. It was a lot of work!

We didn’t use that many miniatures in Rebirth of Mothra III. There were a lot of mass destruction scenes in this movie, but the script didn’t include any mass destruction scenes. Originally, Rodan was supposed to be in the movie, but they decided that he was too weak, so they replaced him with King Ghidorah. The story is about King Ghidorah’s kidnapping children. But, if King Ghidorah is flying in the sky over Nagoya, it would be weird if he doesn’t destroy anything. So I decided to include some destruction scenes and drew them in the storyboards.

I was told, “We don’t have the budget to make miniatures of buildings or towers.” I said, “I know. I’ve thought about how we could shoot these destruction scenes without them, so please let me do this.” I made a demo reel, and they let me do these scenes. By then, we were able to use computers, so all I needed was to shoot the material for the demo reel.

BH: Please talk about special effects director Kenji Suzuki.

KS: When Kenji Suzuki asked me to work with him, I was very happy about his offer because it had been a long time. He let me do what I wanted. Director Suzuki had done the tokusatsu for Ultraman 80 (1980-81) and worked under Mr. Kawakita for several movies. Director Suzuki retired from the film industry at one point because of family circumstances. I think it was around King Ghidorah – Mr. Kawakita bumped into Kenji Suzuki and invited him to work with him.

After that, Kenji Suzuki worked as assistant director for King Ghidorah and Mothra. I said to Mr. Suzuki, “It must be tough directing for the first time.” He said, “Actually, directing is so much easier. It’s much more difficult being an assistant director!” (laughs) That tells you how tough it was to work as an assistant director for Mr. Kawakita. Just watching [the assistant directors], I could tell that it was tough because they were always caught between two fires [a rock and a hard place].

BH: What techniques are used to film tokusatsu?

KS: I was part of the filming team and worked as a cameraman, so my job was to use cameras and lenses to create special effects. With the camera, we would use techniques like time-lapse and high-speed filming. In terms of lenses, we used a range between wide lenses and telephoto lenses. We used different lenses depending on the scene, and my job was to use the right technique to make the miniatures appear to be the size they were supposed to be. In my case, I wasn’t expected to make the miniatures look real. I was expected to make the miniatures look big.

As long as they appeared to be the right size, I was doing my job right. And it was even better if I could give the appearance of more impact. Nowadays, they make things look very real using CG. Sometimes, you can’t even tell the difference between CG and the real thing. But I find that boring. It’s amazing but boring! I guess we expect things to look perfect with CG, but I’m sure it’s difficult to do. But that’s boring. It’s difficult to do tokusatsu with miniatures, but it’s more interesting. I still find it more attractive to shoot with cameras and lenses.

BH: What was it like to work at Toho in the 1990s? How was it different from the 1970s?

KS: Toho disappeared in the 1970s, so I think it’s more the 1960s than the 1970s. In the 1960s, Eiji Tsuburaya was still alive, and there was a team called the special effects techniques team, which specialized in tokusatsu. Within the special effects techniques team, there were teams like the special effects art team and the composite shots team. They made many, many movies, and with each movie they improved their techniques. They also had good budgets.

Eiji Tsuburaya died in 1970, and they dissolved the special effects techniques team that same year. Toho was divided into three companies. The special effects techniques team became Toho Eizo, the special effects art team became Toho Bijutsu and included the regular art team, and the movie section became Toho Pictures. So the foundation for making tokusatsu pretty much disappeared. Yuko [Tomoyuki] Tanaka was the president of Toho Eizo, and he brought a lot of tokusatsu work to the company. This allowed the special effects techniques team, the tokusatsu filming team, and the painting team to survive.

I’m not sure of the exact year, but in the late 1970s Yuko [Tomoyuki] Tanaka became the president of Toho Pictures and was no longer the president of Toho Eizo. From that point on, the special effects techniques team and the other tokusatsu teams were broken up and diminished. So, in the 1990s, Toho no longer had a special effects techniques team and employed freelancers to make tokusatsu movies. That meant that Toho lost the tokusatsu experience it had accumulated.

BH: Why didn’t you work on the Millennium Godzilla series?

KS: I was an employee of Toho Eizo Bijutsu. Until Rebirth of Mothra III, Toho Pictures and Toho Eizo Bijutsu worked together. In other words, Toho Pictures contracted Toho Eizo Bijutsu for the art and tokusatsu work. But, from [Godzilla 2000] Millennium (1999) on, Toho Pictures took over everything, and all the Toho Eizo Bijutsu employees were fired. At the time, Mr. Eguchi was a Toho Pictures employee, which meant that he was transferred to Toho Pictures. From Millennium on, Toho Eizo Bijutsu no longer made any Godzilla series or any other tokusatsu movies. Both Mr. Suzuki and I had been invited to work on the Millennium Godzilla series. But that’s why I wasn’t able to work on the series, which is really regrettable.

BH: How did you join Shin Godzilla (2016)?

KS: When Hideaki Anno and Shinji Higuchi held their Tokusatsu Museum [Tokusatsu: Special Effects Museum] exhibition in 2012, they asked me to film the exhibition. They wanted to archive the tokusatsu event using the old analog techniques. I was the last employee at Toho Eizo Bijutsu to film with the old analog techniques. There were no employees who joined after me. So you could say that I’m the last survivor of tokusatsu. After I filmed the exhibit at the Museum of Contemporary Art [in Tokyo], I was invited to work on the Attack on Titan (2015) movies, and Shin Godzilla came right after that with the same members. That’s how I joined Shin Godzilla.

BH: Please talk about your work on Shin Godzilla.

KS: We used miniatures for Attack on Titan. We didn’t use a horizon [backdrop]; we just used a blue background. For Shin Godzilla, we didn’t even use miniatures. We did use a big puppet for the upper half of Godzilla. There was a person inside who moved the puppet around, but none of those shots were used in the final movie. We filmed everything without Godzilla, who was the main character. We hardly used any miniatures for the destruction scenes, so it was almost entirely done with CG. It was a very unsatisfying experience. I thought, “The time has come when a Godzilla movie is made with CG,” and felt a bit sad. The movie itself is impressive and interesting, but I still felt sad.

BH: Please talk about the Godzilla puppet. Why was it rejected?

KS: I don’t know. I think director Hideaki Anno didn’t want to use it.

BH: What techniques were used to shoot tokusatsu in Shin Godzilla?

KS: In one word, CG. (laughs) There was very little analog shooting. It felt like we were mostly shooting material for composite shots. With Shin Godzilla, I felt that the tokusatsu era was over, which made me a bit sad. It was a good movie, but I still felt sad.

BH: What was director Shinji Higuchi like to work with?

KS: Mr. Higuchi often came to Toho Studios to hang out with Mr. Kawakita and Mr. Nakano. I remember him as a young man who loved tokusatsu. When he came to Toho, we would talk about tokusatsu. He knew so much about tokusatsu and was very interesting to talk to, so I enjoyed our conversations. He came to Toho to work on the 1984 Godzilla movie, then left Toho to shoot Yamata no Orochi Strikes Back (1985).

When we were working on the presentation for Space World in Kitakyushu, we needed someone to draw the storyboards for the presentation. I remembered that Mr. Higuchi was very good at drawing, so I invited him to the staff room, and director Nakano asked Mr. Higuchi to draw some of the illustrations for the Space World presentation. After that, Mr. Higuchi told me he was going to shoot Mikadroid (1991) with Mr. [Tomoo] Haraguchi, and he asked me to shoot the tokusatsu scenes. So I worked on Mikadoroid with him. People at Tsuburaya Eizo saw the rushes and told me how impressed they were. Mr. Higuchi’s career took off after that. Mr. Higuchi came to my home sometimes, so we were close.

BH: Please talk about director Hideaki Anno.

I never really spoke to Mr. Anno. He’s a bit difficult to approach, Mr. Anno. Tokusatsu ended before I really got to know him. One time, when Mr. Higuchi was working on the first Gamera [movie, Gamera: Guardian of the Universe (1995)], I went to Nikkatsu Studios. I was leaving by taxi. I don’t remember why, but Mr. Higuchi was in the same taxi, and Mr. Anno happened to walk in front of the taxi. Mr. Higuchi said, “That’s Mr. Anno.” He wasn’t famous yet, but I knew of him from his anime work. I think he was working on [Neon Genesis] Evangelion (1995-96) at the time.

Mr. Higuchi said, “Mr. Anno also loves tokusatsu. I think you two would get along. I’ll introduce you to him.” We followed him in the taxi, but then Mr. Anno turned into an alley, and we couldn’t follow him anymore. Mr. Higuchi said he would introduce him to him some other time, but that never happened. I think it would have been interesting if we had been able to talk then.

BH: Please talk about working with [tokusatsu cinematographer] Keizo Suzuki.

KS: I worked with Mr. Suzuki on the Tokusatsu Museum, Attack on Titan, and Shin Godzilla. Whenever we worked together, he was very considerate of me. Thanks to him, he made my work as a cameraman a lot easier. He was a Tokusatsu Kenkyujo [a company founded in 1965 by Nobuo Yajima that does special effects for movies and TV] cameraman and loved tokusatsu. He was always thinking about tokusatsu techniques and the future of tokusatsu. I think he’s going to be a very successful cameraman.

BH: Which was the most difficult tokusatsu work?

KS: There were so many! (laughs) There were many movies that were difficult but a worthwhile experience, which made me forget about the difficult times. Whereas the movies that were a bad experience, I only have bad memories of them. In all the movies I worked on, there was always at least one or two difficult moments, but it’s tough to choose the most difficult one. Actually, even if things were difficult at the time, once the movie is done, things don’t seem difficult anymore.

BH: Which was your best tokusatsu work?

KS: Of the movies I was worked on, my favorite is Submersion of Japan. Of the movies I worked on, my best work as a cameraman was the movie version of Gransazer [Super Fleet Sazer-X the Movie (2005)]. It was a tokusatsu movie shot on film. There are others, but they’re drama movies and not tokusatsu. For tokusatsu, I’m going to say the movie version of Gransazer. I still haven’t done my best tokusatsu work yet! I think my next movie will be my best work.