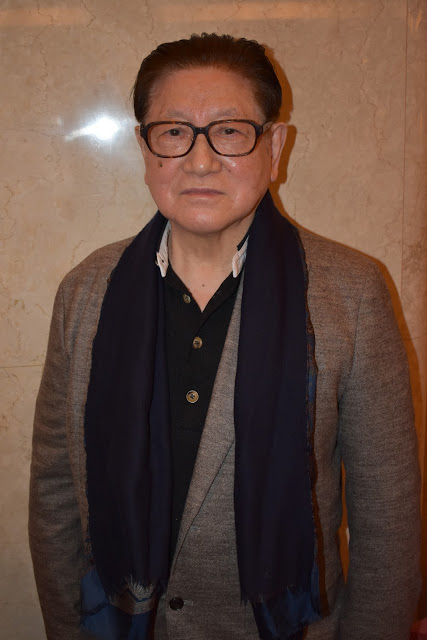

Born on July 31, 1931, screenwriter Fumio Ishimori’s work has touched just about every facet of Japanese entertainment. Hailing from from Haboro, Hokkaido, he joined Nikkatsu as a screenwriter in 1963 and later signed with Shochiku in 1969. In total, Mr. Ishimori has written more than 70 movie screenplays. Mr. Ishimori wrote the screenplays for the films Fearless Comrades (1966), A Warm Misty Night (1967), Toshio Masuda’s Monument to the Girl’s Corps (1968), The Rendezvous (1972), Journey into Solitude (1972), Toho’s Horror of the Wolf (1973), Galaxy Express 999 (1979), and Nobuhiko Obayashi’s The Rocking Horsemen (1992). In terms of TV tokusatsu, he wrote Kamen Rider (1971-73) episodes 47, 50, 76, 83, 89, and 90, Ultraman Ace (1972-73) episodes 37 and 44, and Zone Fighter (1973) episode 20 (under the pen name Shiro Ishimori). But his tokusatsu connections run even deeper — his maternal cousin was famed manga artist Shotaro Ishinomori. In November 2020, Mr. Ishimori spoke to Brett Homenick about his lengthy screenwriting career in an interview translated by Maho Harada.

Brett Homenick: Please talk about your early life in Hokkaido. Talk about what it was like to grow up back then.

Fumio Ishimori: I was born on July 31, 1931. [Next] year, I turn 90. My father was a principal of an elementary school in the mountains, and I was the eldest son. After the war, the only thing that there was to do was watch films. So I just watched a lot of movies because I was living in the countryside. I watched Japanese as well as foreign films.

In the morning, I would go to class. In the afternoon, there were two screenings. There was one at 1:00 p.m. and another at 7:00 p.m. There were only two theaters in town, and they only had two screenings. But, in the afternoon, the classes were really boring, so I wouldn’t go to school. I’d skip class and just go watch movies. But I was getting good grades, and I was at the head of my class. However, I was still skipping class to go watch movies.

One day, the principal of my high school said, “Come to my office.” He said, “You’re skipping class and watching movies.” So I said, “One day, I’m going to be involved in films and become famous. So I’m doing this because I want to get closer to my dream. I’m doing this for my future.” The principal was an idiot, so he said, “Don’t come to school anymore; you’re expelled.” My father was also a principal of an elementary school, so my high school principal called my father and told him that he kicked me out of school. My father didn’t say anything about this to me when he got home. So I went to class the next Monday, and the teacher got angry. He said, “You’ve been kicked out of school! Why are you here?” So I said, “Just pretend I’m not here.”

I used to sit at the front of the class, but I decided to sit at the back of the class. I said, “Don’t worry, I’m only here until noon, anyway. Then I’m going to go watch a movie.” So I was always kind of a rebel.

The war ended on August 15, 1945, and I started junior high school in April 1944. Back then, Japan was considered the land of the gods, and we didn’t believe that we would be defeated in the war. Basically, people said that it wasn’t important to study academically; what was important was to train to become a good soldier. So nobody considered that Japan would lose the war. But I thought we would definitely lose the war.

Every morning at 7:00, we would do exercises in the school courtyard, and they would play music during the exercise. But, one day, they didn’t play the usual exercise music. Instead, they played the news that Japan was now at war with the U.S. and England [after the attack on Pearl Harbor]. At the time, I was probably in the fourth or fifth grade. I decided to take out a world map. I looked at the map, and I saw how Japan was shaped like a little chili [pepper]; it was so small. Then there was the Pacific Ocean, and the United States was very, very big. I said, “How is it possible for Japan to win against such a big country?”

My father said there was no way we were going to win the war. I was very surprised because my father was a school principal, and, in my heart, I wanted my father to say, “Don’t worry, we’re going to win.” But my father said, “There’s no way we’re going to win.” So I was very surprised. Then my father said, “Idiot!” I thought my father said “idiot” to me, but he was actually saying that to Hideki Tojo, who was the most idiotic prime minister in the history of Japan. As a child, I was quite surprised.

I remember in my childhood that things were very abundant. I could go to the store and buy whatever I wanted. But then, over the next two or three years, the rationing system was introduced where sugar, rice, and everything else was rationed. Things disappeared from the store, and you couldn’t buy anything. So I sensed that the country was getting poorer and poorer, and I thought, “There’s just no way Japan could win.” So, when my father said “idiot,” I was so surprised that I almost fell over.

Anyway, my father went to the school where he was the principal the next Monday, and I learned about how adults have to behave. At home, he was saying there was no way we could win. But then at school he was saying, “We have to be very Japanese, and we are going to win the war.” So I sensed that adults had a different way of living. I also sensed that I was not quite like ordinary people. My belly button is not in the same place as everyone else’s belly button. I couldn’t accept what others perceived as common sense. I always have my own thoughts and have to try try them out before I’m satisfied. Then I form my own opinions. I think, as a child, I was not the cutest; I was not very obedient.

BH: What were some of the movies that you watched at the time that you enjoyed?

FI: I have something I’d like to add. Back then, they weren’t called eiga [movies]. They were called motion pictures. So I loved going to the theaters, and because my father was a principal, he would get invitations to go watch films. But I would get motion sickness because of the flickering, so I would bring a cushion with me to the theater. I would get motion sickness and feel sleepy, so I would fall asleep. Thus, I would only see the first scene and last scene. But I still loved films, and I would go see them all the time.

I remember in high school that the teacher would say that only bad students would go see movies. I was always going to the movies, and the teacher would grab me and say, “You want to watch a movie; you’re such a bad student!” I would actually be made to go onstage in front of the whole school, and the principal would lecture me and say, “This is an example of a bad student who goes to watch films. You should not be a bad student like him.” So going to watch a movie was the equivalent of being a bad student.

But then, one day, the teacher said, “Tomorrow at 9:00, the entire class will go to the theater to watch a movie,” because it was a war movie. I thought that was so illogical; it didn’t make sense that if you go to watch a movie by yourself, you’re considered a bad student. But, if you go to watch one in a group, it’s fine. That didn’t make sense at all. So I just pretended to have a headache that day and didn’t go because I thought that films are something that you enjoy alone. I just did not agree with the idea that it was fine if you went in a group but not alone.

However, these kinds of teachers’ attitudes changed after the war. There were posters for American films, and their catch phrase was, “The source of culture.” I thought it was unbelievable that a person could change what he was saying so much. So I decided that I wouldn’t just be a somewhat bad student; I’d be a full-on bad student. I’d go to school in the morning and then go watch films in the afternoon.

One day, when I was watching a movie, I had a vision. During the movie, a red ball came flying toward me from the other side of the screen, and I caught it. I remember getting this message that one day my name would appear on the screen as a staff member. So I thought about these things when I was watching films. My father, grandfather, and uncles had all gone to school to become schoolteachers and eventually principals, and it was expected that I would also become a schoolteacher like my father. But, in my heart, I had decided to go to Nihon University College of Art and study film. I decided to do that because I knew my name would appear onscreen.

One day at school, at the end of October, when everyone was preparing to take college entrance exams, the principal called me and my teacher to his office. He handed me an envelope and said, “Take this to your father and get him to sign and seal it.” It was basically a recommendation for Keio University. Because the principal of my high school had gone to Keio University, he was allowed one student whom he could recommend, and that student would get accepted. It’s a very prestigious university, and I wouldn’t even have had to go to Tokyo to take the entrance exam.

I had very good grades, so I could have gotten into Keio University on his recommendation. But I handed the envelope back to the principal and said, “I don’t need this. I’m going to the Nihon University College of Art to study film.” When we went back to the classroom, my teacher said to me, “You idiot! You don’t even have money. What a stupid idea to study film!” He said that to me in front of the class, so he embarrassed me in front of the whole class. I got very angry and just lost it, so I said, “You’re only able to become a schoolteacher in this countryside school! How can you know my future?” My classmates said, “You must have really been angry to say that kind of thing!” But how could some countryside schoolteacher know what I was capable of doing?

So I was obsessed with films, and I was convinced that I would be involved with films, and that I would get there on my own merits. It was something I dreamed about, and I really wanted to jump into this world. My father said, “It’s not that easy.” When I was graduating, because my father had a lot of connections as a principal, he found me a job at a bank. But I said, “I’m very sorry, but I’m not going to work in the countryside after university. I’m going to realize my dream on my own and be recognized for my efforts.” So I remember when I was going to Tokyo for university, my mother took me to the station and said, “Fumio, we don’t have money in this family to allow you just to enjoy your hobby at university.” That really stung my heart; those words are carved into my heart forever. Actually, it was a source of courage for me.

When I got into university, I wrote my first screenplay. It was 280 pages, and it was my first screenplay ever. It was called “Evening Bell.” This script actually won an award with the Japan Writers Guild. I applied for their script contest and won an award with honorable mention. Because it won an award, it was published in a magazine. So, at 19, I had my first screenplay appear in a magazine. For me, it was a message to my mother that I wasn’t in Tokyo just to have fun; I was there to realize my dream. Even if I was invited, I didn’t go drinking, and I didn’t play mahjong, like all the other students. I was there to make my dream come true.

After graduating, I went to Nikkatsu, but it didn’t go as I planned. It took time to gain recognition. When I graduated, my professor said, “It will take 10 years for your name to appear onscreen, so just be prepared.” At the graduation party, all the students said what their dreams were, and I said to my classmates, “Please remember my name, Fumio Ishimori. You can expect to see my name onscreen in 10 years.” It actually took nine years to happen. My first film was The Rumored Wanderer (1964).

BH: What movies [did] you watch at the time that you were interested in?

FI: This particular film I remember watching when I was in the fourth or fifth grade was called Navy (1943). It was based on a novel written by Bunroku Shishi, whose real name was Toyoo Iwata. It was a beautiful film. I remember being very moved by it and understanding how to structure a story and drama. It’s not just about the characters but also their internal conflicts and the things that they go through in the drama and how to move people. I felt this in the fourth or fifth grade. I’ll never forget this movie. I think it was made by Shochiku, and the director [Tomotaka Tasaka] was somebody who was in Hiroshima at the time of the bombing. The screenplay was by Tsutomu Sawamura. Mr. Sawamura was actually recognized as a screenwriter when he was still a student at Tokyo University. I happened to see this film when I was still in Hokkaido. When I won the award for “Evening Bell,” Mr. Sawamura recognized my talent, and I became his student. So, while I was still a [university] student, I studied under Mr. Sawamura. So it’s very interesting how thing happened.

It was because my script for “Evening Bell” was published in a magazine called Scenario. That’s how my teacher Mr. Sawamura learned about me.

While I was still in university, I went back to Hokkaido during summer or winter break. But, after I graduated, I didn’t go back. I didn’t want to go back, even if my father found me work, and it would have been an easy life. I didn’t have money; I just had my dream and the determination to make it on my own. I had this connection with Nikkatsu that didn’t go as planned, but in the ninth year, I saw my name appear onscreen. I did everything I could to make it day-to-day until then. But my dream was just to make it in the film industry.

In film, there are two pillars. One is the melodrama pillar. Kogo Noda, a Shochiku melodrama writer, was one of my professors at university. I really learned how to write screenplays for entertainment melodramas from him. The other pillar is for realism. It was a contrast from Mr. Noda, and I learned that from Yasutaro Yagi, with whom I worked at Nikkatsu. His name has been carved into the history of Japanese film.

Mr. Yagi was a very, very scary teacher. He would say, “This is a terrible script! That’s because you’re a student and haven’t seen much of life yet!” He was really criticizing “Evening Bell,” my script. My classmates said, “It’s amazing you didn’t commit suicide because he was being really harsh on you.” Any ordinary person would feel that they weren’t talented and would be in despair, but I’m not an ordinary person. I just wondered why he was being so harsh on me and made such a big deal out of something that a student had written. But it ended up winning an award and being published in a magazine. Basically, what Mr. Yagi was trying to teach me was the importance of being humble and not to think that I was being arrogant. I worked on Monument to the Girl’s Corps (1968) with Mr. Yagi at Nikkatsu. It featured Sayuri Yoshinaga and became a very popular film.

BH: Do you have any memories of the war and the hardships in Hokkaido?

FI: During the war, I was a student and just skipping class and getting kicked out of school. I was just obsessed with films; I couldn’t see anything else. I was pretty much blind to everything else. If I had worked at the bank job my father had found for me, I probably would have gotten the most beautiful woman who worked there, and I would have had access to all this money that wasn’t even mine. I probably would have used it all! Because it was other people’s money, I would have used it as my own money; I know myself. You know yourself better than anyone else. So I basically would have been tempted by a woman and money. So I would have spent all the money. If you had all this money in front of you, wouldn’t you spend it all, too? So I know I would have been tempted by a woman and money. That’s why I didn’t work there.

BH: What did you have to do to join Nikkatsu?

FI: There were two ways. You could write a screenplay and then be recognized. Or you could write a plot. There were these meetings that happened every Friday. At the time, they released two movies every week. So they had to make lots of movies — one short and one long feature film. So they had to make many movies. The second method was writing a plot and having it get recognized, and then you would get a two-year contract. There were a lot of writers who wrote one screenplay and then got a contract. But, if you don’t write a screenplay in two years that was used, then you would get fired. I wasn’t interested in doing that. I wanted to be working for 10, 20, 30, 40 years. It’s still the case now, even though I’m 90.

I got the formula in terms of how to structure the story and how to write a plot that would be approved or that would get used. After I graduated, I was teaching at university. One of my students said that he received one of my plots to study how to write a plot that would get used. So that’s how much I was able to write plots that would get used.

BH: How long would a short movie be?

FI: The short one would be 4,000 feet of film, and the long one would be 7,500 feet of film.

BH: Who were your friends at Nikkatsu?

FI: One was my fellow screenwriter Iwao Yamazaki [the real name of Gan Yamazaki, who co-wrote 1967’s Monster from a Prehistoric Planet, a.k.a. Gappa the Triphibian Monster]. He wrote the Rambler [movie] series with Akira Kobayashi and Ruriko Asaoka. Nikkatsu would put us up at a Japanese inn where the scriptwriters would work overnight, writing scripts. It became legendary because both Mr. Yamazaki and I would be writing really fast on a writing pad that everybody used. When we finished a page, we’d tear it from the pad and place it on a pile. The others wouldn’t be able to write as quickly as we could and said they were troubled by the sound of pages being torn coming from Mr. Yamazaki and me. The two of us could finish a script in three or four days. We competed with one another to see who could write faster.

There are 200 characters to a page, which goes very quickly. It makes a really good sound when you tear the sheet from the pad. It’s a really good sound; I really enjoyed that.

BH: You would be in the same room?

FI: We were in different rooms, but we could hear this sound at night. The other screenwriters wouldn’t be able to write at all, so they would just hear the sound of pages being torn out from both of us. (laughs) We would all be in our own rooms, and the rooms were next to one another, so the others could hear this sound. Nobody else would be able to write; they would just be stuck with ideas. But Mr. Yamazaki and I would be writing [by hand]. I wanted to go home, so I would write as fast as I could. (laughs) So I would just go at ripping speed.

BH: When you said that you wanted to go home, was that just you or both?

FI: Mr. Yamazaki had this [makes the gesture for having a mistress or girlfriend]. Mr. Yamazaki went to Korea and had a relationship with an actress. This actress actually showed up at Nikkatsu, so I was the one who had to turn her away and say, “He doesn’t love you. He’s not a responsible guy.” Mr. Yamazaki was very fast with women, so he had a lot of girlfriends. I’m too scared of the consequences of having an affair; I couldn’t have had one!

BH: So this would be at Nikkatsu Studios with the offices of all the writers.

FI: No, they would put us up at an inn and give us each a room. They were producing so many films, so we had to work overnight. They just gave you a room, and basically you just had to keep producing scripts.

BH: Would the writers be able to come up with their own ideas?

FI: Every Friday, there would be a plot meeting to decide which ones would get used. We would write the plots ourselves and then write the script if the plot was approved. Because I’d already written the plot, the story was already in my head. I would write them starring Yujiro [Ishihara] or Sayuri [Yoshinaga]. That’s why I was able to write them very quickly. Because we all worked exclusively for the same studio, we had a contract. So we were involved from the writing of the plot, and then we would write the screenplay for the ones that got approved. Because we had written the plot, we knew exactly what’s going into the story, so that’s why we were able to write the script so fast.

BH: Next, let’s talk about A Warm Misty Night (1967) with Yujiro Ishihara. Please talk about writing this script. Were there any requirements since Mr. Ishihara was a big star?

FI: Not at all. Mr. Ishihara was a very humble person. In terms of the script, there were no limitations at all. I remember at lunchtime each actor would be sitting with his team. There would be Yujiro Ishihara and Akira Kobayashi. It’s not that they didn’t get along; they just had their own teams, their attendees, manager, or staff members, and they would eat at their own table. Because A Warm Misty Night was my first script [for Mr. Ishihara], someone took me to Mr. Ishihara’s table and said, “This is the new guy. He wrote the script for A Warm Misty Night.” He was very humble, so he stood up right away. He was very tall, and he said, “Thank you for writing the script for this movie.”

He invited me to go on his yacht, but because I’m so susceptible, I got seasick in about three seconds. So I started vomiting and couldn’t really enjoy it. Mr. Ishihara had been boating since he was a kid. I don’t drink, and I don’t smoke, so if I could have gone on the yacht without throwing up, maybe I could have met many beautiful women. But I just ended up vomiting.

I remember the screening for Monument to the Girl’s Corps. I was sitting behind Mr. Yagi. Mr. Yagi was just livid because the story was supposed to be a home drama. It was originally about a family that was leading a simple, peaceful life and how they became victims of the war. It was supposed to be about the sense of futility surrounding that family. The director was supposed to be Kenjiro Morinaga, but at some point, Toshio Masuda became the director. Mr. Masuda took this family drama and somehow turned it into a war movie.

Mr. Yagi was very angry about that. He left the screening room, and he was waiting for Toshio Masuda and the assistant directors to come out. As soon as they came out, he yelled, “You idiots! What were you thinking? How dare you turn this into a war movie!” Mr. Yagi was livid; it was quite a sight. He had written the script for Kenjiro Morinaga, who was an incredible home drama director. That’s why Mr. Yagi yelled, “How dare you turn this into a war movie! You idiot!” at Mr. Masuda. I was impressed.

Mr. Yagi and I wrote the film together. It wasn’t at all the ending that we had written in the script. We actually went to Okinawa to the cave where the 30 girls had committed suicide with grenades in their hands. Next to the cave, there is the Himeyuri Monument with all the names of the victims. The last name you see is Ken-chan [the name of a boy]. We don’t know for sure why he was with female students — maybe he had lost his parents. But, for some reason, he was with these female students, and he ended up dying with them. So, in the last scene that we wrote, the vice principal writes down the names of the students who were in the cave to commit suicide, and the last name he writes in the notebook is Ken-chan. Then the vice principal also dies. That was the story we had written because we wanted to write about ordinary people and how unfair it was for them to die because of the war.

But it really depends on the director. It’s a lot of work to write a script from scratch. You start with nothing, but you create the story, and you have a message. That was our message. But the director cut all that out and created his own ending. The story suddenly begins with the war, and the girls are nurses. They knew nothing about being a nurse, but he suddenly turned them into nurses. They look after injured soldiers and go to the cave with the soldiers, then end up committing suicide there. It doesn’t make sense, and the ending was very dull. That’s why Mr. Yagi was livid and yelled, “You idiots! You turned it into a war movie!” at the screening. The message we wanted to give through the movie was the importance of peace and how war tramples over it. But our efforts went to waste.

BH: Did you have any dealings with director Toshio Masuda?

FI: I hate him. He was not able to depict people. It’s all just about style. He cannot depict the inner conflict that human beings have. His work was quite rough [unrefined].

BH: On a lighter note, there’s Fearless Comrades (1966). Please talk about working on this movie and with Mr. Kobayashi.

FI: He’s all talk. Once, when he came to see Mr. Yagi, he said, “Ishimori’s scripts aren’t interesting. He needs to have more fun with women. Then he’ll write better scripts!” So he asked Mr. Yagi if he could take me to Kobe to have fun with women. Mr. Yagi said, “Good idea!” But Mr. Kobayashi never fulfilled this promise, so I’m still asking him to take me to Kobe to have fun with women! It still hasn’t happened, and I reminded him the other day about that. He said, “You’re still talking about that?” That idiot. He’s all talk. No wonder he’s only been in superficial movies.

Until we worked together on Fearless Comrades, Mr. Kobayashi was often in these action movies with guns and pistols. But it doesn’t make sense because in Japan it’s illegal to have a weapon. How would you get a gun? You would immediately be arrested. Mr. Kobayashi was in all these action movies with guns, but Nikkatsu decided that people didn’t want to see these kinds of movies anymore and asked me to write an action movie with Akira Kobayashi that didn’t involve guns. However, in the last scene, it was unavoidable; he picks up a pistol that was on the floor that belongs to his opponent. But he doesn’t shoot him, he just shoots the gun out of his opponent’s hand, and peace is restored in the neighborhood. He leaves, and there’s guitar music. Basically, I’ve never seen a gun in my life, so it’s hard to write about something I don’t know. In Japan, it’s illegal.

The Invincible One (a.k.a. The Man with Nine Lives, 1967) was written by another screenwriter [Hisataka Kai] and me. But the other screenwriter never worked because he was completely obsessed by stocks. So he would always leave, going to buy stocks. That was his last film; he never worked as a screenwriter after that. I think he became addicted and eventually disappeared.

I believe that you have to work alone to write a proper script. Eventually, I was handpicked by Shochiku, and I started working for Shochiku. After that, I worked alone. You’ve probably seen The Rendezvous (1972) and Journey into Solitude (1972). I worked with director [Nobuhiko] Obayashi on The Rocking Horsemen (1992) and wrote Galaxy Express 999 (1979). I wrote those scripts alone. You have to write scripts on your own and not depend on other people. The worst ones are those who take off for a drink in the middle of the day and don’t work!

BH: At Nikkatsu, how long would it take you to write a script? How many rewrites would there usually be?

FI: It was about five to six days. Because I was on a contract, it was very cheap; it didn’t pay very well. It was 400,000 yen per script.

BH: Would there be a rewrite?

FI: No. It would be printed as soon as I handed it to them. Because they were always in a rush, they would just start filming right away. They didn’t have time for rewrites. Everyone was on a contract, even the actors. The studios like Nikkatsu and Shochiku would cast it right away. There was no time for rewrites.

BH: For Monument to the Girl’s Corps, how long did it take the two of you to write the script?

FI: One month. We went to a Japanese inn in Izu and stayed there until it was done.

BH: Was that the longest [it took to write a] script?

FI: It was the longest. We would first think about the structure of the story. There’s something called hakogaki — box memo. It’s a small piece of paper that describes one scene, the theme, who does what, and the acting for that scene. The movie was about two hours long and had about 200 scenes. So we made 200 of these box memos. We had a very big table, and we would spread them out on the table. We might move a scene around if it fit better somewhere else, or we might combine two scenes into one if they were very similar.

So, before we actually started writing the script, we went through this process. Once we started writing, it was very quick, and it only took about 10 days. The rest of the time, we were writing the box memos.

BH: So that would be 20 days, basically.

FI: Yes. We would write the box memos from scene 1 to scene 200. Because we went through this process first, the screenwriting was done very quickly. In film, I had a lot of experience writing the box memos and preparing the story. But, for TV, I just had the character names to write the script, nothing else. For the TV series Hissatsu Shigotonin (1979-81), I wrote about 80 episodes. The writing process for this series was about six hours for one episode. It was about 100 sheets of paper with 200 characters on each page. I would stay in a Japanese inn in Kyoto. I would start at 10:00 a.m. and had to finish by 4:30 p.m. because the printer would come to pick it up. Once I finished, I would head back to Tokyo.

By 9:00 p.m., they would finish printing, and by 9:00 a.m. the next day, they would start filming. So, after I gave the script to the printer at 4:30 p.m., I would come back to Tokyo, and then I had more work for TV. So I did 80 of those episodes. They still show the reruns of these period dramas on TV, so even when I see them now, I find them very interesting. I had this momentum when I was writing them. I had a lot of fun. Sometimes, there would be consecutive episodes with my scripts broadcast on TV.

BH: Let’s talk about the end of Nikkatsu and your relationship [with the studio]. How did that end?

FI: At the time, Shochiku had fired a lot of its contract writers because they were not very talented. They went through a restructuring and got rid of people who weren’t producing good work. So they had a lack of writers. They were looking for somebody to write youth-oriented dramas. A young producer found that I was talented and asked, “Would you like to work for us? How much are you making now with Nikkatsu?” I said, “Four hundred thousand.” He replied, “We could offer you 500,000 yen per film.” Eventually, the contract was worked out so that I would make one million yen per film, and the contract stipulated that I would make two films per year. So that meant that I would make two million yen per year. Then they calculated how much that would be per month, and they paid me a salary that was deposited into my bank account on the 25th of every month. So life became much more stable, and my wife was relieved. Shochiku also promised that if I made three movies a year, I would make three million yen per year.

So, once I joined Shochiku, my life was more stable, and I was emotionally more stable, too. Shochiku as a company was a good fit for my personality, so I was able to concentrate and produce good work. This kind of structure doesn’t exist anymore; now it’s done on a production basis where they offer 10 million yen per film. But I really wanted to make melodramas because all the classics like Gone with the Wind (1939) are melodramas. That’s the kind of film I wanted to write. So that’s what I did at Shochiku because they invited me to do that kind of thing.

When I got bored of melodramas, I started to do other things. For example, when somebody said, “Mr. Ishimori, there are too many lines in your films,” I turned it around, and I wrote a film called The Rendezvous. In that script, there are no lines until page 25. The film Journey into Solitude was the first road movie. It was about this girl [played by Yoko Takahashi] who goes on a road trip by herself. Usually, screenwriters are very quiet. I’m the only talkative screenwriter, so people always comment about how I’m the only talkative screenwriter. I love talking to people, so I want to know about people, what they’ve experienced, what their hobbies are, and what they’re thinking. To do that, you can’t communicate with your eyes; you have to talk, you have to use words. But other screenwriters are quiet; I’m the only talkative screenwriter.

BH: Let’s talk about tokusatsu, and let’s talk about Kamen Rider (1971-73). How did you get hired to write Kamen Rider episodes?

FI: My son used to watch Kamen Rider, which was on Sunday nights at 6:00. At the time, Kamen Rider was an idol for all the kids. When my son was in the fourth grade, he was bullied at school, and they said, “Hey, your father is a scriptwriter; why isn’t he writing scripts for Kamen Rider?” I was writing scripts for more serious adult dramas that would be shown at 8:00 with Toshiro Mifune. But, for kids, it was all about Kamen Rider. I thought, “Oh, my goodness, I have to do something for my son.” Because I was being paid more per script, I was overqualified to write scripts for children’s TV shows.

Luckily, a university classmate, Katsuhiko Taguchi, worked for Channel 12 [now TV Tokyo] and was a director for Kamen Rider. So I went to Mr. Taguchi and said, “My son is being bullied, so I really need to do this. Can you help me?” At the time, a lot of scriptwriters my age had kids who were in elementary school, and they all wanted to write scripts for Kamen Rider. But none of them worked out because they only knew how to write scripts for adult dramas. Mr. Taguchi said, “It’s very unique. It’s for kids, it’s for 30 minutes, and you need a monster. So you need ideas. It’s quite different from other work.” And it was true. Screenwriters who wrote scripts for children’s TV shows could come up with one idea after another. He told me, “You probably won’t be able to do it.” But I said, “Look, my kid is being bullied at school. I have to do something.” So Mr. Taguchi said, “OK, come up with two or three stories, and we’ll see.”

I wrote three 30-minute episodes. It wasn’t that hard; I just had to write 40 to 45 pages [of 200 characters per page]. I went to Mr. Taguchi’s company at 9:00 a.m. the next morning, and Mr. Taguchi was very surprised. He said, “That was really quick!” He was expecting it would take about a week. I said, “Look, it’s for my son. I’ll do anything for him.” Mr. Taguchi read the scripts in front of me and said, “This is actually very interesting.” He brought in a producer who said, “We’ll use these.”

They started shooting the first episode right away, and I did about seven or eight episodes. By the seventh or eighth episode, my son was in the sixth grade. It was Sunday night, and my son was at his desk, studying. At 6:00, I said, “Hey, Kamen Rider’s going to be on TV!” My son said, “You’re still writing that?” He had stopped watching Kamen Rider and was studying for his junior high school entrance exam. So I started for my son, and then I quit because my son wasn’t interested anymore. It’s all about my kids; I’m a stereotypical father who’s crazy about his kids.

Mr. Taguchi, the director who helped me out in this situation, recently passed away because of the coronavirus. He saved my life. He was going for monthly check-ups and went for his usual check-up by bicycle. At the hospital, they said that something was wrong. He got transferred to the Red Cross Medical Center, and he died that night. His wife was not even able to see his body. He was cremated the same day, and she was given his remains. Ken Shimura is another close person to me who died due to the coronavirus.

BH: When you were writing Kamen Rider, what approach did you have to the material since it was so different?

FI: I took three scripts that were already written for Kamen Rider and figured out the formula. Basically, you have a monster [that belongs to] Shocker, and you just need to decide how you’re going to fight it. You just have to come up with an interesting idea, and you can write one episode in 15 minutes. Maybe I’m exaggerating. But I could write an episode in an hour. Normally, for an hour-long TV show, you would need three climaxes. But Kamen Rider is only 30 minutes, so you only need two climaxes, one before the commercial break and another after the commercial break. It’s very easy; it’s like a walk in the park. Once you figure out the formula, you don’t have to think too hard. You just have to figure out the monster, how Kamen Rider is going to fight it, and the monster’s weakness. For the first episode I wrote [episode 47], the monster was Todogiller (a.k.a. Sealioller). He lives in icebergs and threatens to turn Tokyo into an iceberg. With a single breath, he could freeze anything.

BH: How did you get inspired to come up with monsters?

FI: It’s for kids, so you just need to come up with characters that kids would find interesting. Todogiller came to freeze Tokyo over, so you freeze the main character. Then you figure out how to unfreeze him, and then you decide how you’re going to fight the monster. You only have two climaxes, so it’s pretty easy. But it’s fun. I had a lot of fun.

BH: What about your relationship with Shotaro Ishimori? Please talk about your relationship and connection with him.

FI: He’s a maternal cousin. His actual name is Shotaro Onodera. He became a very important person, and everybody called him shacho [“boss,” “CEO”]. But I just called him Shotaro. He lived in a house with a pool. He passed away quite young of cancer.

BH: What was he like as a person? What kind of a relationship did you have?

FI: He was crafty. Just like me, he was very positive, optimistic, and interested in lots of things. We come from the Sendai clan that was based in Sendai, which was historically quite well-off. My family was the karo [chief retainers of a feudal lord] and were given 1,200 koku [units of rice given to a feudal family]. But Shotaro’s family were farmers. He was from the Onodera family, which was part of the Date Clan.

There was a small castle in a town called Ishinomori in Miyagi Prefecture. But, when there was a merger of small towns, the town of Ishinomori was about to disappear. So Shotaro asked our family if he could use the name Ishinomori because he wanted to preserve this piece of history. My family said it was fine to use the family name because he was from the maternal side. Historically, it was actually pronounced “Ishinomori.” My elder uncles called themselves Ishinomori, not Ishimori, because they had a fortune teller look at the name, and the fortune teller said, “You should change it to Ishimori. Ishinomori is bad luck.” He probably died early because he used a name that brought on bad luck. But I called him Shotaro, and he called me Fumio. We were on a first-name basis.

My name is pronounced “Fumio,” but most people thought it was pronounced “Shiro.” So assistant directors and everyone else called me “Shiro.” I didn’t have a choice, so I just answered to “Shiro.” But I asked the women I slept with to call me “Fumio.” There’s a world-famous Shakespeare researcher named Yui Odajima, and I told him about this policy. One time, there was a very famous stage actress, and she inadvertently called me “Fumio” [in front of him]. I fell out of my chair!

BH: Did you really sleep [with her]? Was that just an accident?

FI: I really did sleep with her; it was not by accident! (laughs) Everyone found out about us, so I was like, “Oh, no!” She was a famous actress who was the star of a theater group.

BH: Going back to Kamen Rider, there’s also [directors] Issaku Uchida and [Masahiro] Tsukada. Did you work very much with them? Do you have any memories?

FI: Mr. Uchida made a lot of films. He graduated from Waseda University. Mr. Uchida’s younger brother was a very famous producer [Yusaku Uchida] who worked on Kamen Rider at Toei’s number-two studio. He was also the president of the company that created Kamen Rider and made a lot of money for the company because he was very good at selling Kamen Rider merchandise. They worked together with Bandai to sell the merchandise.

BH: What’s your favorite episode of Kamen Rider?

FI: The very first one [that I wrote].

BH: Let’s talk about Ultraman Ace (1972-73).

FI: I wrote two episodes of Ultraman Ace. I shouldn’t have done that because Toho made Ultraman, and Toei makes Kamen Rider, and they’re rivals. I kind of broke a rule that shouldn’t have been broken. But somebody asked me to do it, and I said, “Sure, sure.” That’s how it happened. But, in the end, I’m glad I wrote it because a student of mine said there was one episode of Ultraman Ace he could not forget that he watched as a child [episode 44, “Setsubun Ghost Story! The Shining Bean”]. In February, we have this tradition of Setsubun [during which we throw red beans to ward off evil spirits and protect the home] where you eat the same number of red beans as your age to stay healthy. The story was that there was one red bean that would turn you into an evil monster if you ate it.

So my student watched this episode as a kid, and because kids are naive and can’t make the distinction between reality and TV, he thought it was real and couldn’t eat any beans on Setsubun. To this day, he can’t eat beans on Setsubun. So this episode instilled this kind of fear in my student, but it also drove him to become a scriptwriter. He writes scripts for Ultraman now. So the red bean episode became an inspiration for him. He also studied under me. This made me very happy because you can write hundreds of scripts that leave no impression. But you can write one script, and it can leave a lasting impression on somebody.

My favorite food is umeboshi. You don’t have that in the States, but I think it’s the best food in Japan. So this student’s grandmother would send me homemade umeboshi every umeboshi season. I was very grateful for that. That’s another thing that came from that episode. I think it’s the best food in the world.

BH: Was there ever a concern that the Setsubun story might be too scary?

FI: I think it’s too scary. But I didn’t think much about it when I wrote it.

BH: What inspired you to write it?

FI: I was requested to write a story that was related to Setsubun, so I just decided to base the story on the tradition of throwing beans, which my father used to do. You wish for the evil monsters to leave the house and for good fortune to come in. That’s what you say when you throw the beans. It’s one of the traditions that represent the four seasons and life in Japan, so I thought it would be interesting to use that tradition. Even though it was too scary, I liked the idea of there being one red bean that would turn you into a monster if you ate it. The American equivalent would be Halloween, and you’d have a red candy that would turn you into a monster if you ate it. Like that, you could turn anything into a story. I can think of an infinite number of ideas like that. Trick-or-treating is scary, as well, because all these different candies come from different people. Someone would eat the red candy because they thought it would taste good. The idea would be something scary like that.

BH: What about director Masanori Kakei on Ultraman Ace?

FI: I’ve never worked with him. I only wrote two episodes of Ultraman Ace because I was also doing Kamen Rider. Toho and Toei were rival companies. (laughs) They were competing for ratings. They [Toei] said, “What were you thinking, writing for the rival company?”

BH: Do you remember who contacted you from Tsuburaya Productions or Toho to write that?

FI: I’m part of the [All Nippon] Producers Association. Every year, they have a party, and I go there every year because there are people I only see at this party. I might not be alive next year, or another member might not be alive next year, so I make it a point to go every year. I don’t drink, but I love to talk and see familiar faces. At one of the parties, an Ultraman producer came to me and said, “Could you please write an episode or two for Ultraman because it’s becoming the same old thing, and we want something unique.” So I said, “Oh, no problem.”

BH: Also, at Toho, you wrote for Zone Fighter (1973). How did you get that job? Talk about the process of writing that script.

FI: I wrote under a different name — Shiro Ishimori. But I used a different character for shi [in Shiro]. Instead of the character “history,” I used the character “poem.” I used a different name.

BH: Why did you change [your name]?

FI: Because it was for a rival company, I decided to use a different name. Also, it was because a fellow producer told me, “Don’t write for every company out there and cheapen your name.” So I decided to use a different name and chose the character for “poem” because I really like that character.

Do you know who Heine is? He was a Jewish poet [from Germany]. When I was a child, I was very impressed by a poem written called “Around Maytime.” I was very impressed by this poem and can still recite it today; it’s an unforgettable poem. I’ve always loved poetry, so that’s why I used this character in my pen name.

BH: Please talk about how you got hired to do Zone Fighter and the process of writing it.

FI: At one producer meeting, a producer asked me if I could write a script, so I said, “No problem,” as I always do. The producer said, “The scripts that are coming out are not the stories that I want. It’s the same old thing, and it’s getting boring. Can you come up with something?” There were a total of 13 episodes – I think it only ran for one season. I told him that I would write two episodes. I agreed to do it but decided to write under a pen name using the character “poem.” It was a henshin [transforming superhero] show, but a different kind of henshin show.

I can’t remember his name, but the director [Masao Minowa] was also a graduate of Nihon University College of Art in film studies. After graduating from university, he started working for a production company as an assistant and had just become a director. I thought, “For somebody that young, he’s quite deep.” I think he experienced a lot of difficulties as an assistant director. So this director wanted to make a different kind of henshin show. I can’t remember his name, but I wonder how he’s doing. When I found out that we had graduated from the same university, I said, “Sure, sure, no problem!”

It was a very interesting and unique henshin series. But, because it was too different, it wasn’t very popular. So the ratings weren’t very high, and it only lasted one season, but there was something very impressive about it. It was different from Kamen Rider and Ultraman. I thought it was good, but it didn’t last.

BH: Do you have any other memories about Zone Fighter? Is there anything else you could share about it?

FI: I just remember that it only lasted one season and that I did it because the director was a graduate of the same university as I did. But I do have another memory about Kamen Rider. Everything would wrap up at 5:00, and at 4:30 there would be this foreign car — an expensive, luxurious car — that would come to the studio. It belonged to the Hatoyama family [a famous Japanese political family]. I was very good friends with the younger Hatoyama brother [Kunio]. He would come to pick up Emily [Takami], who eventually became his wife. She was still in high school and was a child actor in Kamen Rider.

Kunio Hatoyama was a very famous politician, a member of the [Diet’s Lower] House. He would come in this expensive car every day to pick up Emily, who doesn’t look Japanese. The Hatoyamas are a very well-known political family. I was very close with the Hatoyama family, and they had a rose garden party every year that I would attend. I can’t drink alcohol, only juice, but I went, anyway.

BH: Let’s talk about Horror of the Wolf (a.k.a. Crest of the Wolf, 1973). Please talk about the process of writing [it].

FI: I was really good friends with the producer, whom I saw at the Producers Association. He said, “There is no one at Toho who can write this script. Ishimori, you can write anything. Do you think you come up with a script?” The original book was written by Mr. [Kazumasa] Hirai, and it was about the wolf legend in Japan, which I loved. It’s based on the fact that there are no more wolves in Japan. Wolves usually travel in packs, but Japanese wolves traveled alone. I think they all died of an infectious disease or something because they’re very sensitive animals. But, in Mr. Hirai’s novel, one wolf survived. I loved the idea of one wolf’s surviving and felt inspired to write the script. I had never written this genre before, so I thought it would be a good challenge. It was difficult to write a script about a legend that was based on something that had actually happened. It’s so mysterious to think that, at one time, there were wolves in Japan.

The main character was somebody who had become very popular and become a star, playing [Minamoto no] Yoshitsune in an NHK drama, Taro Shigaki. So the casting had already been decided. I was intrigued by the story when I read the original book. It was about a wolf’s transforming into a human being. This was exactly the kind of story I would have written. I had worked on so many scripts, but this was the first time I had the chance to write something like this. So I definitely wanted to do this.

I wrote the first draft, which I thought was really interesting. But the producers and director made a mess of it and changed the ending, so the story didn’t make sense anymore. So, in the end, I’m not proud of this script; I think it was a failure. But one good thing that came out of this movie was the lead actor, Yusaku Matsuda, who took up the challenge of playing a wolf that turns into a man. I saw this actor at the theater group Bungakuza. I went during a rehearsal, and there was one guy doing stretches in front of the mirror. He had arrived early, before anybody else. He was stretching and his T-shirt was covered in sweat. You could tell by its color that he only had one T-shirt. It would get covered in sweat, then he would go home and wash it and wear it the next day. This actor turned out to be Yusaku Matsuda. I said, “That’s the guy.” He went on to become an amazing actor in Japanese films. He even acted opposite Michael Douglas in Black Rain (1989). But he became very sick and died of cancer, coughing up blood, which was a shame.

He was of Korean descent, so he was always bullied at school because he wasn’t Japanese. But he became very strong; he was good at fighting. My previous wife who has since passed away had heard about Mr. Matsuda and how he was always in fights to defend fellow Korean kids. They were from the same area. She didn’t know him directly, but she had heard of him because he was known for defending Koreans who were bullied by Japanese. He would show up and fight whoever was doing the bullying. So he had the reputation of being scary, but he was also known for looking after others. It wasn’t like he took money from the person after he beat him up. But he might have; you never know!

BH: What was the original ending that you wrote?

FI: It was the story of a human being who becomes a wolf. It wasn’t just about a guy who philanders with a woman and fights some guys. I read up a lot about wolves and their characteristics and used that in the script. When there’s a full moon, and the Moon is very bright, he has a lot of power and is able to transform. He can win fights because he’s strong. But, when there’s no Moon, he’s very weak. Apparently, that’s how wolves are — when there’s no Moon, they hide in a cave and don’t fight at all. So, the only way you could defeat him is to attack him on a dark night. Yusaku lived in a mansion because his father was known as “the Prime Minister of the Underworld” because he controlled the financial world. But you can’t let this happen in a democratic society, having one man control everything. So the main character has to fight everyone, including the father.

The director [Masashi Matsumoto] was in love with an actress named Wakako Sakai. He even declared publicly that she was the only person he would ever marry. So he wanted her to be the lead actress, but she had only played innocent roles until then. She would have had to play a woman who gets stripped naked and gets attacked by a wolf in this film, so her agency refused. So they chose a different actress [Yoko Ichiji] for the role. She wasn’t bad; she was very courageous and showed her breasts in the film. But she just didn’t have the charisma — the sexiness or innocence that could drive a man insane. She didn’t get the nuance right of portraying the purity of a virgin. So, unfortunately, the climax lacked thrills because it wasn’t well-developed.

The enemy figures out that the best time to launch an attack on the wolf is on a dark night and drives the wolf into a basement where he can’t see the Moon. For the wolf to have power, he needs something that would replace the Moon, something that would shine like the Moon. [In my original script,] I came up with something that was not in the original story. I thought hard about what could replace the Moon to give the wolf power. After a long time, I realized that a round fluorescent light would be perfect because it’s round, and it gives off a bluish light like the Moon sometimes does. Last night was such an example of that; the Moon actually had this bluish light. With that light, the wolf would be able to gain power and fight off Yusaku Matsuda and everything he represents.

The wolf is an innocent youth who can only live a pure life. The real climax was his defeating evil — those who abuse their power to do as much evil as possible and control the financial world. But we don’t need any of that in this world, do we? So the wolf destroys everything, including the mansion. But they changed the ending; it’s not the ending I wrote. After the screening, the producer said, “This is not what I had in mind. What a shame.”

BH: The co-writer of the script is Jun Fukuda. Did you have any dealings with Mr. Fukuda as a co-writer of the script?

FI: Jun Fukuda was my senior at university and a director at Toho. He asked me to participate, so that’s how we became co-writers. But his intentions were different from mine. This is why the ending was changed. It was basically the same situation as Monument to the Girl’s Corps. Once the shooting starts, the story is under the reigns of the director. Once the script leaves the hands of the writer, it’s up to the director. The film will be in the director’s name, and he makes the film he wants to make. I still regret those two films because the last scenes were completely changed. For any film, the last scene is what really makes a film. Whether it’s an action film or if there’s a lot of killing in the story, if you’re moved by the last scene, then the audience will think, “I’m so glad I watched this film.” It’s the only way you can give back to the audience who pay to see your film. I’ve always had this intention of giving back to the audience, and writing a moving ending is the only way a screenwriter could do that.

The ending I had in mind was the wolf’s disappearing into the darkness. That would have been the last scene. Even if there was no Moon, that would have really left an impression on the audience. They would’ve thought, “We’re only human beings; we cannot control nature because it has its own order. You can’t fight it.” So this wolf that doesn’t need to exist in the world stills exists, and you see the ruins of this once-amazing mansion. You see the wolf’s walking quietly away, disappearing into the darkness. But the director changed it to the ending he wanted. As a screenwriter, I have certain themes I want to work with, and I want to depict characters and their inner conflict. You have to give back to the audience because they’ve paid money to see the film. Films are all about entertainment.

As a child, I loved going to see motion pictures, and all the ones I was enthralled by had a moving ending. That’s what I wanted to do — write stories that would be moving and leave a lasting impression, and have my name appear at the end in the end credits. If the ending is amazing, then the movie itself is amazing, isn’t it?

BH: What was your working relationship with Mr. Fukuda like, writing the script?

FI: Mr. Fukuda didn’t write anything. I wrote the script, and Mr. Fukuda would just give his opinion of what I had written. He would say, “Change this,” or, “This should be like this,” because he was a director. He eventually did write his own screenplays for his own films. But what I felt then was that Toho, Nikkatsu, Shochiku — each company had its own way of writing scripts. At Shochiku, I would write out every single detail. You could basically shoot each scene exactly as it was written in the script. But, at Toho, the director would make all the decisions in the shoot, so they didn’t need to write out the details in the script. So the scripts were very rough and quite dry.

Each studio had its own way of doing things, and that was also reflected in the way the scripts were written. For me, the Shochiku way of writing screenplays suited me very well. Everything was very detailed in my scripts, including the acting, so you could shoot each scene just by reading the script. So I really enjoyed this work.

BH: On this movie, the director was Mr. Matsumoto. Do you remember working with Mr. Matsumoto at all as the director on this film?

FI: This movie was originally Mr. Matsumoto’s idea. He had actually wanted to make this film for a long time, and he wanted to use Wakako Sakai. I think he should have just written the script on his own and not involved me. When Toho makes films, they end up being action films. So they wanted to involve me is because I’m very good at melodrama, and they wanted to add a sort of sweetness to the film because otherwise it doesn’t leave a lasting impression. They didn’t just want to have action because nobody is moved by action. They wanted it to be a love story — a man falling in love with a woman and being willing to die for her. And, in this case, it’s about a wolf, so there’s even more depth to the story. It had to be a melodrama, and Mr. Fukuda thought so, as well. That’s why they asked me to write the script. Mr. Fukuda and I had the same intention, but it was the director who had something else in mind.

BH: What do you think is the best movie that you’ve written?

FI: The best film that I wrote is The Rocking Horsemen, except for the last scene. I was very disappointed because if you know rock music from that era [the 1960s], the last song that they used didn’t exist at that time. There’s [‘60s] rock, like the song “Pipeline” [by The Ventures], but then by the ‘80s, music is completely different. But, in the last scene, they used music from the ‘80s that didn’t exist when the story took place. So I went like this [makes a facepalm gesture] when I saw the screening. I thought, “This guy doesn’t know rock.”

In the script I wrote, rock started with “Pipeline.” When I first heard this music, I felt like I’d been struck by lightning. When men are moved, they don’t feel it in their hearts; they feel it in the most important body part to men. It’s not intellectual. When I first heard this music, that’s how I reacted. it’s more sort of primal – more animalistic. I didn’t know I was such a pervert! This isn’t just for music, but for any kind of emotion.

I like to walk around town and spot dandelions. In Tokyo, the dandelions are the Japanese type, and they’re very small. But [William S.] Clark, who said, “Boys, be ambitious!” brought the American variety of dandelions to Japan. They grow in colonies in Hokkaido, so when I go to Hokkaido, I look for them as soon as I arrive. They can grow anywhere. They’re very tall, strong, and very male. Do you know what they’re called in English? Dandelions — they’re lions! It’s my favorite flower. The dandelions in Hokkaido are exactly like the phrase, “Boys, be ambitious!” The dandelions in Tokyo – the Japanese kind – are really small, but the ones in Hokkaido are fierce. Also, I was born on July 31, so I’m a Leo. That’s why I feel like it’s my flower. I feel like dandelions flower just for me.

There’s a group from the U.S. of five or six members called The Ventures. When they came to Japan, the first thing they performed was “Pipeline.” It’s a very electric sound, and the sound of the electric guitar hits you. The sound is electric, and it passes through the mike and the speakers, so it’s really intense. It’s not at all like a Japanese guy just playing his guitar. It really makes your blood scream, and you feel the sound of the electric guitar. It really has punch when they’re strumming the guitar. Young guys who played the guitar were really impressed by this, so they started playing the electric guitar because the sound was completely different.

So many people wanted to make this movie [The Rocking Horsemen] in the States. American producers approached us so many times about making this movie in the States, but it never worked out. I think it’s impossible for Americans to make this film. It’s only possible in Japan because rock was born in States, so I don’t think it’s possible to make this movie in the States. They tried to make the film in the States three times. Each time they said, “This time it’s going to work.” But every time it failed because it’s not possible to do it in the States. [in English] I think so.