Photo © Perry Martin.

In September 1989, The Super Mario Bros. Super Show! debuted nationwide, marking the first time the Super Mario Bros. franchise had ever been adapted into a cartoon show. For American children who had been growing up on a steady diet of Nintendo video games, it was one of the most highly anticipated TV programs of the era. The cartoon show also proved to be an early break in the career of series scriptwriter Perry Martin, who at the time was trying to secure a foothold in the entertainment industry. Mr. Martin would also go on to write for sequel series The Adventures of Super Mario Bros. 3 (1990) and Super Mario World (1991). In September 2018, Mr. Martin answered Brett Homenick’s questions about his contributions to the Super Mario Bros. franchise, as well as a few monster-related topics. (Special note: The images accompanying this interview were kindly supplied by Mr. Martin from his personal collection.)

Brett Homenick: Please tell me about your background before you broke into the entertainment business.

Perry Martin: I was born in 1958 and raised in Yuba City, California — a small, semi-rural town just north of Sacramento. It was a nice, safe, wholesome time and place to grow up, not unlike the old Andy Griffith Show. Everyone seemed to know each other. Many people never bothered to lock their doors. You could easily ride your bike from one end of town to the other, and the rest of world seemed like a distant planet.

My father was an architect and my mother a teacher, so I had a happy, comfortable middle-class upbringing. I had a sister, friends, a pet beagle and a paper route. My dad loved movies and would take me out every Friday night to one of the two theaters in town — always the highlight of my week. That’s how I first became interested in film. Of course, there was also a whole universe of older movies and shows on TV, which I explored avidly. Growing up in a small town, before the Internet, TV and movies were your windows to the outside world — and that world seemed so much more interesting and exciting than the one I lived in.

BH: I understand you grew up as a “monster kid.” How do you define “monster kid”?

PM: The term “monster kid” refers to a generation of children that grew up in the late 1950s and early ’60s when the horror genre was booming. The whole “monster craze” started in 1957, when the classic Universal horror films were sold as a package called Shock Theater to local TV stations, which began running them, usually on Saturday nights, introduced by ghoulish hosts like Zacherley and Vampira. All across America, these decades-old monster movies started earning smash ratings — and their core audience turned out to be children.

Soon after, Famous Monsters of Filmland hit the newsstands, and that magazine became a rallying place for young horror fans. Suddenly, monsters new and old were everywhere. England’s Hammer Films was churning out their Technicolor remakes of Frankenstein, Dracula and The Mummy. Roger Corman was in full swing with his Edgar Allan Poe movies starring Vincent Price. Godzilla films were pouring out of Japan. Ray Harryhausen was blowing everybody’s minds with his stop-motion animated monsters. TV Shows like The Outer Limits, The Munsters, and Dark Shadows were all on the air and filled with monsters. You could find monster-themed toys, games, trading cards, comics, and paperbacks in the bedrooms of kids all across America — often well hidden from their parents.

BH: Why did some kids feel they needed to hide those things?

PM: It’s probably hard for younger fans to understand because horror, science fiction, and fantasy are now mainstream, but when I was growing up, those genres were sort of disreputable — actually, they were really frowned upon. Many adults believed that there had to be something seriously wrong with you if you liked those things. A lot of parents put monsters in the same category as cigarettes, drugs, and pornography, which only added to their allure.

I was lucky enough to have parents who encouraged and supported my interests. Every year, my mother would fly me down to Los Angeles to attend banquets at the Count Dracula Society, where I got to hobnob with guys like Fritz Lang and Lon Chaney, Jr. I also got to know Forry Ackerman, editor of Famous Monsters, who took me under his bat wing. The first play I ever wrote was an adaptation of Dracula, which I produced for my 6th grade class. I played Dracula, too.

Left: Perry (age 11) as Dracula in a school play. Right: Perry (age 13) on Creature Features with Bob Wilkins. Photos © Perry Martin.

Every week I used to write letters to Bob Wilkins, my local horror movie host, with information about the movies he was screening, and he would sometimes read them on the air. Then when I was 13, Bob even invited me to be a guest on his show. So I became pretty well known around town as the resident horror movie expert/nut, depending on how you felt about such things.

BH: How did you discover classic horror films, and which ones do you enjoy?

PM: My first encounter with classic horror movies came on Christmas Eve 1964 at the highly impressionable age of six. My parents had taken me out to do some last-minute shopping at the local Sears and dropped me off in the toy department where my wandering eyes eventually fell upon a display of Aurora monster models. Well, that incredible box art by James Bama just stopped me dead in my tracks. It was truly love at first sight. I stared at those boxes, transfixed and hyperventilating, until my parents finally came back and dragged me away.

Over the next few years, I saved enough dimes and nickels to buy all those kits and built them, but the films that inspired them eluded me. We only had three TV channels back then, and they apparently had no interest in monsters. I was really frustrated about that. Then, on Halloween night of 1968, I came home from trick-or-treating (dressed as Dracula) and found my Dad watching Bride of Frankenstein on TV. Cable television had just hit town, and one of the new stations was running the Shock Theater package. After that, I was glued to our TV every Saturday night and, in a few short years, could’ve obtained a doctorate in monster movies.

As I grew older, that obsession eventually led to a serious interest in the history, art and craft of motion pictures. My tastes have broadened and matured considerably, but I still enjoy most of the classic horror films and revisit them regularly to see how they’re holding up — like old friends.

BH: How did you become involved in the entertainment industry?

PM: Growing up, I thought I wanted to be an actor, and performed in a lot of school and community plays. Eventually, I studied theater at a community college and later at San Francisco State University. But after graduating, I realized that I really wanted to write and maybe direct movies. So I worked a soul-crushing retail job and started writing in my free time. Basically, I taught myself how to write. I was still living in San Francisco then.

After a year, I completed my first screenplay and submitted it to the American Film Institute, and was accepted into their MFA program. I moved to Los Angeles and studied screenwriting at the AFI, where I had instructors like Robert Wise and Edward Dmytryk. That was a great experience. Then I got my first job in the industry as a script reader/analyst for producer Sandy Howard (A Man Called Horse, Island of Dr. Moreau). I worked for Sandy for several years, reading scripts and eventually writing a couple for him, neither of which got made. It was a rather inauspicious beginning but at least I was earning a living.

Left: The American Film Institute’s Center for Advanced Film Studies in Los Angeles. Right: Perry during his time as an AFI screenwriter fellow (1983). Photos © Perry Martin.

BH: It’s interesting you worked closely with Sandy Howard. Japanese monster movie fans may know him as the director of the American inserts of Gammera the Invincible. What do you remember about working with Mr. Howard?

PM: Sandy was a brash, larger-than-life New Yorker who reminded me of an old-school movie mogul — the kind of guys who came from nothing and fought for everything they had. A big part of this business is salesmanship, and Sandy had a gift for the hard sell. I mean, that guy really knew how to fill a room. He could be very tough and abrasive. I’d never met anyone like him, and he actually scared the hell out of me. I also thought Sandy had terrible taste — but maybe I shouldn’t say that since he liked me and my work! The first script that I wrote for him was a mob comedy, a cross between The Godfather and It Happened One Night. Sandy really loved that script but was never able to raise the financing to make it. He was quite a guy — far more admirable than I understood back then.

BH: What led to your being hired on The Super Mario Bros. Super Show?

PM: After a couple of big flops like Meteor, Sandy Howard fell on hard times and finally had to let me go. So I was back pounding the pavement, a struggling writer looking for work. It’s no secret that it’s hard to make a living in this business, especially on the creative side. So I worked a lot of odd jobs to make ends meet, writing nights and weekends, and taking advantage of whatever opportunities came my way. Eventually, I learned that it was relatively easy to break into TV animation — it was non-union, so that door was a little more open than others.

To be honest, I had no particular interest in writing cartoons beyond the chance to get paid for it. So I learned the process. First, you contacted the story editors of a series in development and requested a show bible, which outlined the concept, characters, and types of stories they wanted to do. From that, you wrote a premise — a one-page story idea — and submitted that to the story editors. If they liked the premise, they’d hire you to turn it into an outline then a script.

So I contacted a number of animation companies and started submitting premises to them. I don’t know how many I cranked out, but it was a lot. None of them sold, and I started to get discouraged. Eventually, I got my hands on the bible for a show called C.O.P.S. — a futuristic take-off on The Untouchables being produced by DIC. I submitted a number of premises for that — one of which was “The Case of the Baby Badguy,” about a gang of criminal dwarves hiding out in an orphanage disguised as abandoned infants. Now, I thought that concept was so strong that if it didn’t sell, I’d just throw up my hands and quit trying to write cartoons.

But the next day I got a call from one of the story editors, Bruce Shelly, who loved the idea and wanted to buy it. So I wrote that script and it came out well. In fact, the producers liked it so much that they hired me to write a sequel, which was unusual. Eventually, DIC filled their order on C.O.P.S. and moved on to other projects, but I had a feeling something more was going to come of it. Sure enough, a few months later, I got a call from Bruce asking me if I’d like to write for their next show, Super Mario Bros. He and his writing partner Reed, who also happened to be his son, were already working on the first two episodes, and they wanted me to write the third.

BH: How familiar with Mario were you when you were hired?

PM: I’d heard about the game, which was hugely popular, but I’d never played it. I wasn’t into Nintendo and had no interest in it whatsoever.

BH: What sort of rules or guidelines did you have to follow when writing your scripts? Was there a series bible?

PM: The bible was written by Bruce and Reed Shelly. Reading it, you could tell that they were still struggling to get a handle on the show. I mean, the core problem was obvious: There are no real characters or stories in a Nintendo game, so how do you turn one into a TV series? The bible indicated that Mario and Luigi would have a jokey rivalry like Bob Hope and Bing Crosby from the old Road pictures, with Mario being the fun-loving adventurous type, and Luigi being timid and cowardly. The Koopa was described as a big, ugly, reptile with a personality like Don Rickles. Princess Toadstool and Toad were very thinly defined.

There was little indication about the kinds of adventures our heroes would have, and a lot of unanswered questions about how we would incorporate elements of the game. I had no clue how to solve those problem and didn’t see how that show was going to work at all! But DIC had an order for 52 episodes and deadlines were looming. We had to make some decisions fast or fall behind schedule, which would be a disaster. So at the beginning there was a lot of urgency to solve those problems and get on with it.

BH: Most of the episodes of the Super Show are movie parodies. What was behind the decision to take that approach?

PM: That angle was not part of the bible. I believe the decision to go in that direction finally came from Andy Heyward, president of DIC. It may not have been the most original answer to the question of what kind of stories we would tell, but it was a very practical one. At least it gave us a handle on the show. It was certainly better than spinning our wheels. All the game-related elements became incidental, which didn’t surprise me. Perhaps we should have made more effort to incorporate those things, but you can’t build 52 stories around guys chasing after magic coins. Anyway, the first story they gave me was a reworking of the King Arthur legend, which became “King Mario of Cramalot.” That was the first of the parodies.

Model sheet for “Mario Meets Koop-zilla.” Photo © DIC Entertainment.

BH: You wrote the episode “Mario Meets Koop-zilla.” As a lifelong Godzilla fan, I’m curious to know your inspiration for this particular episode. Where did your ideas come from?

PM: That was the second one I did, which I sold to DIC as a premise. Obviously, as an ex-monster-kid, I was very familiar with Godzilla, and thought a Godzilla parody would be a natural for the series — especially since our villain was an overgrown lizard. Before writing it, I re-watched a bunch of Toho movies to refresh my memory and see what ideas I could mine from them. I had a lot of fun writing that episode, and it’s probably my favorite of the ones I did.

I remember Andy Heyward loved my premise and script, and was very complimentary about both. He particularly liked the way I’d structured the story. In the first scene, our heroes arrive in a strange land and immediately encounter the Koopa, who’s up to his usual no-goodery. The rest of the episode is our heroes’ response to the Koopa’s shenanigans. That became a template for the episodes that followed — at least it was in my mind. Very simple and straightforward.

Model sheet for “Mario Meets Koop-zilla.” Photo © DIC Entertainment.

BH: Were you working on staff or as a freelancer?

PM: As I said, Bruce and Reed brought me in early to help iron out kinks in the show and write one of the first episodes. But I was still working as a freelancer — going through the usual process of submitting premises and hoping for a sale. At the same time, I was also holding down a nine-to-five job as an office clerk, so I’d get up at 3 o’clock every morning, write until dawn, then head off to my “real” job.

I’d tinker around with my scripts on my lunch breaks, then come home, eat dinner, go to bed around 8 p.m., then get up at 3 the next morning and do it all again. I wrote my first two Super Mario scripts that way. I think Bruce and Reed were auditioning me for a staff position but wanted to be sure I could deliver before bringing me on full-time. After I sold my third premise, “The Adventures of Sherlock Mario,” I got a call from Reed, who asked if I’d like to quit my day job and go to work for them.

Model sheet for “The Adventures of Sherlock Mario.” Photo © DIC Entertainment.

BH: Were you excited?

PM: You bet. That was a big break for me. A funny thing happened when I reported for work. I’d developed a good relationship with the staff administrative assistant, a real nice guy named Bill Ruiz, who was also responsible for assigning offices. When I showed up bright and early on my first day, Bill led me down the hall to a magnificent corner office. It was right next door to the office that Bruce and Reed shared, but much bigger and nicer than theirs — with a spectacular view of the San Fernando Valley. I couldn’t believe my eyes. I thought, “Holy shit! I’ve arrived!”

Well, that lasted about five minutes. Just as I was unpacking my computer, Bill came back, saying he’d made a mistake and had to move me to another office. I’m sure somebody’d got wind of what he’d done and told him, “You can’t put that kid in there!” And it would’ve been awkward if they’d needed that big office later for another story editor or producer. So Bill moved me a few doors down to a small windowless room — more like a closet — and that’s where I worked for the duration.

Losing that fabulous office was a letdown, but I didn’t really mind. I was thrilled to have that job and determined to do the best work I could. Besides, the only window that a writer needs is the one sitting on his desk.

Model sheet for “The Adventures of Sherlock Mario.” Photo © DIC Entertainment.

BH: You must have felt a lot of pressure to deliver.

PM: I did. The first script I wrote on staff was “The Adventures of Sherlock Mario,” based on the premise I’d sold to them. Again, I watched a bunch of Sherlock Holmes movies for inspiration. When I finished the script, I walked across the hall and gave it to Bruce, then went back to my office and waited. A couple minutes later, I could hear Bruce chuckling as he read it.

He even read one scene out loud to Reed — the bit in which Mario is tied-up by the Koopa, and escapes by eating a meatball sandwich, causing his stomach to bulge, breaking the ropes. Then I heard Bruce say that sequence was “really well thought out.” After he finished the script, he crossed the hall and told me how much he liked it, beaming like a proud father. I guess he felt like I’d rewarded his confidence in me. That’s one of the nicest memories I have associated with that show.

BH: Who would you say was overseeing the day-to-day production?

PM: The only people I really worked with were Bruce and Reed. Writing is a lonely business. You sit there in your office, hammering away on your computer, and often have little or no contact with the rest of the team. But I believe Robby London supervised the production. What little contact I had with him was always pleasant. I know that Andy Heyward read all of the scripts and had final approval on everything. Andy was a polished and charming guy, and always very gracious to me. The directors and artists worked on another floor and I never met any of them.

BH: Did you write the live action sequences with Mario and Luigi, or just the cartoons?

PM: I had nothing to do with those sequences and have no idea who wrote them.

BH: Did you have much interaction with the voice cast such as Lou Albano, Danny Wells, Jeannie Elias?

PM: No, I never met them. I wasn’t present for the recording sessions.

BH: How long would it take you to write a script?

PM: In all, a couple of weeks. After your premise was approved, you had to write a 4-page outline — usually, that’d take two days. Sometimes you had to revise it based on the notes you’d receive. That’d take another day or two. Once the outline was approved, you’d write the script. The average script was about 20-pages long and took about a week to write. Now, in a perfect world, you’d have a lot more time than that. But series television is not a perfect world. It’s a factory. So you do the best you can under those conditions. Writing those scripts, you’d often have to go with your first ideas, knowing you could come up with something much better if you had more time. But you never did. So you just got on with it, learned what you could, and hoped the next one would be better.

BH: What was your approach to the characters?

PM: As I said, the bible indicated Mario was the rambunctious one, and Luigi was the coward. Those characters didn’t run any deeper than that. Princess Toadstool was a stock fairy-tale princess, but she was plucky and could be useful for conveying exposition. Toad didn’t have much of a character, but his voice could add rhythm and humor to the banter. The Koopa was easily the most enjoyable character to write. He was such a big, pompous blowhard — and they’re always fun to set up and knock down.

But let’s face it, those characters were all stereotypes. Today, it’d be impossible to do some of the jokes we did back then, given the current political climate. On the other hand, there’s no time for nuance in a 13-minute cartoon — which means you often have to use stereotypes as shorthand. I plead guilty to adding all of the Italian food jokes, an idea I contributed and relied on heavily. Probably too heavily.

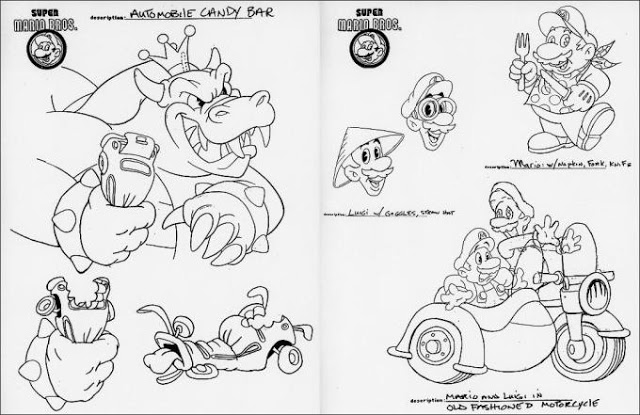

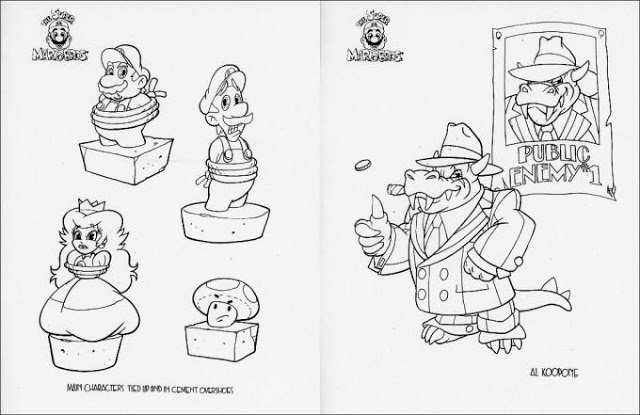

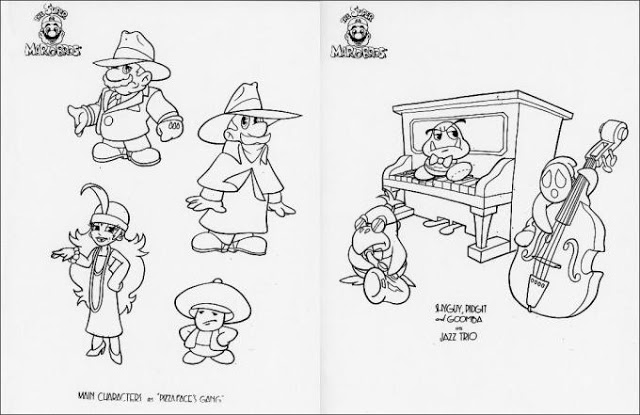

Model sheet for “The Unzappables.” Photo © DIC Entertainment.

BH: “The Unzappables” is one of my favorite episodes. Of course, it’s based on The Untouchables. What do you remember about writing the script?

PM: That one started with Andy Heyward. Early on, we had a meeting up at his house in Studio City — Bruce, Reed, Andy, and me. I believe it was on a weekend afternoon, and lunch was served. This was the meeting where we hashed out how to handle the show, and Andy settled on the idea of doing parodies. He came up with “The Unzappables,” and it was one of the ideas he was really keen on. Luckily, that script fell to me. I knew that premise would be an easy sale because Andy wanted to do it. And the script did turn out well. I’d really hit my stride by the time I wrote it, and everything seemed to fall right into place. It was a solid script.

Model sheet for “The Unzappables.” Photo © DIC Entertainment.

BH: That episode has a lot of clever lines, and the concept is really fun. What were your inspirations, and how did you come up with the idea of making King Koopa and his cronies “unzappable”?

PM: That idea came from Andy’s title — I had to come up with some way to justify it. Of course, the “unzappable” power had to belong to the villains, not Mario and Luigi; otherwise there wouldn’t have been any problem for our heroes to solve. As far as my other inspirations, I guess that’s one way all of my movie-watching paid off. Monster movies may have been my favorite genre as a kid, but I’ve always liked all kinds of movies. I’d seen all the classic gangster movies with Cagney, Bogart, and Robinson, so I knew all the tropes and had fun playing around with them.

Model sheet for “The Unzappables.” Photo © DIC Entertainment.

BH: Were any of your ideas or jokes rejected for any reason?

PM: Sure. That’s all part of the process. I did one premise called “Koop-Tut,” with the Koopa running amuck in ancient Egypt. That was a good story built around a clever plot device. The Koopa takes over Egypt, turns everyone into bricks, and uses them to build a colossal monument to himself, the Koopinx. I thought that idea was clever because it solved one of the biggest problems in animation: crowds. You can’t show thousands of mushroom people running around like some Cecil B. De Mille epic. Everything has to be simple because you don’t have the time or money to do anything else.

So I thought I’d solved that problem elegantly: all the mushroom people had already been turned into bricks at the beginning of the episode, so you never need to see them. I sent that premise upstairs with pride, and was really crestfallen when it came back rejected. Bruce broke the news to me, saying that the powers above might not have understood it because it was “too imaginative.” I thought that was no reason to reject something, so I did a few tweaks on the premise and resubmitted it as “The Ten Koopmandments” — remembering that The Ten Commandments was one of the movie parodies that Andy wanted to do. Well, lo and behold, this time they went for it!

Model sheet for “The Ten Koopmandments.” Photo © DIC Entertainment.

BH: Of course, there were occasionally errors in animation. What was the reaction to these mistakes among the staff?

PM: This may surprise you, but I learned right away that it was best not to look at the final product — and I rarely did. I came to that realization with the first cartoon I wrote, “The Case of the Baby Badguy.” I thought the animation was so bad that it just ruined everything I’d tried to do with that script. It wasn’t the fault of the art department guys at DIC. They did a good job with their designs and storyboards, but then it all got shipped overseas, which was where the animation was done — very quickly, cheaply and poorly.

Reed once told me a story about using the phrase “riding shotgun” in a script for another series, and when the show came back, that phrase had been taken literally, and his character was actually riding a shotgun. The show aired that way because nobody wanted to spend the money to fix it.

Anyway, when the first episode of Super Mario came in, Reed asked me if I wanted to watch it with him. We popped it into a VCR, hit “play,” and almost threw up. So looking at the final shows could be very demoralizing, and I avoided it. As far as I was concerned, my work was on a page. It was my responsibility to make that work as good as I possibly could. What happened to it afterwards was out of my hands.

BH: What was the production process?

PM: Once approved, the scripts went straight to the art department. There the artists would do conceptual drawings and work with the directors to transform that script into a storyboard, which would then be sent overseas for animation. Animated scripts are very different from live-action scripts. When you write a script for an animated TV show, you’re essentially directing on paper. You include all the camera angles and moves. That’s a big no-no in screenwriting, but it’s essential in animation because it helps the storyboard artists understand your intentions.

All modesty aside, I’ve always been skilled at thinking visually and conveying those ideas in writing. I think like a director and understand how films are shot and cut together. Even though I never met any of the storyboard artists at DIC, word filtered down to me that my scripts were consistently the best in that regard, and that the directors and artists vied to work on them. I’m proud of that.

BH: How many scripts did you end up writing for the show?

PM: About ten — it’s hard to say exactly because some of those scripts were re-writes that I did uncredited. We had some good writers working on that show, experienced guys who knew what they were doing, but some of the scripts that came in needed a lot of work. As story editors, Bruce and Reed had to get them into shape. I didn’t envy them because some of those scripts were just terrible. Sometimes, Bruce and Reed would get behind schedule and ask me to do one. Some of the rewrites I did were so extensive that Bruce told me he was going to add my name to their credits, but that never happened.

BH: Which episodes of the Super Show were you asked to rewrite? Why weren’t the original scripts accepted, and what did you bring to them?

PM: In fairness, those scripts had to be written fast, which meant that some of them were delivered to us before they were ready. Now, those weaker scripts might’ve had some good ideas rattling around inside them, but they needed refining. The original writers probably could’ve done that work in additional drafts, but we couldn’t wait. I don’t remember all the shows that I contributed to, but I know I did a polish on “Mario and Joliet” and a complete re-write of “On Her Majesty’s Sewer Service,” the James Bond parody. I was a big fan of the Bond films, so that was fun. I was particularly pleased with the “Wheel of Misfortune” sequence, the torture-themed game show with Vampa White.

Model sheet for “On Her Majesty’s Sewer Service.” Photo © DIC Entertainment.

BH: For “Raiders of the Lost Mushroom,” the character of Indiana Joe doesn’t have a face. It’s widely speculated that this was a mistake on the part of the animators, yet it’s hard to believe that such a mistake would make it to air. What’s the real story?

PM: All I can tell you is, that’s not how I wrote it. In my script, the character is described as “a dashing caricature of Harrison Ford in a leather jacket and a fedora hat.” But when the designs came in from the art department, the guy was faceless. At the time, I assumed that meant his face had not been finalized and the artists were still working on it. But if the show went out that way, then it was probably because of legal concerns.

Perhaps DIC was afraid of getting sued by Harrison Ford or George Lucas. I think they could have come up with a better solution, but again, that was out of my hands. By the way, that was the last script I wrote for the show — and the worst. I remember handing it in to Bruce with an apology, saying that I’d just run out of ideas for the series. He smiled and told me not to worry about it — that it happens to every writer, including him. He was very kind. I liked and respected him a lot.

Model sheet for “Raiders of the Lost Mushroom.” Photo © DIC Entertainment.

BH: How were the songs chosen for inclusion, and was there ever any concern that their use might inhibit future home video releases?

PM: That’s a good question, and I can’t answer it. From the beginning, it was determined that there would be a musical sequence in every episode. The songs were chosen in advance and their placement was to be called out in the scripts. The rights would have been cleared for television, but home video was in its infancy, so I wouldn’t be surprised if nobody gave it much thought.

BH: This might be too obscure, but would you happen to remember if you came up with any of the catch phrases, such as Koopa’s line, “He who koops and runs away lives to koop another day,” or the “Pat-a-cake, pat-a-cake, pasta man” song?

PM: “He who koops and runs away…” was one of my lines, which I wrote for “King Mario of Cramalot.” That’s a spin on a famous couplet by the Irish novelist, Oliver Goldsmith: “He that fights and runs away, may turn and fight another day; but he that is in battle slain, will never rise to fight again.” I think that line is used in the classic swashbuckler The Prisoner of Zenda, which is where I must’ve heard it. I don’t know who came up with the “Patty cake” song, but there’s a running gag in the Crosby-Hope Road pictures that’s very similar, so I suspect it originated there.

BH: Were there any differences between writing for the Super Show and Super Mario Bros. 3?

PM: After we wrapped on the Super Show, I was on my own again. To be honest, that came as a surprise — I thought DIC was planning to keep me on to work on other stuff. I sat in my little windowless office for another week, waiting for my phone to ring, until word about that reached Robby London. He came downstairs and told me I was done, apologizing for not letting me know sooner.

So I packed up and left, and went back to freelancing. I worked on some other shows after that, then Bruce called to let me know they were doing Super Mario 3. DIC had a much smaller order for episodes this time, so there was no need to hire a staff writer, but they wanted to give me a couple of assignments. Originally, “7 Continents for 7 Koopas” was going to be a two-parter. I wrote the outline with that in mind, then got word that it was to be one show only. Condensing that story down to a single script was a challenge, but I did the best I could with it. The other episode that I wrote, “Oh, Brother!,” was based on an idea of Reed’s. I thought that script turned out well, but I never saw what they did with it.

BH: Do you remember what else you planned to include with “7 Continents for 7 Koopas”?

PM: I had the seven Kooplings getting into trouble all over the world, each with their own relatively elaborate sequence. In most cases, those sequences had to be condensed down to one or two shots, and a line of dialogue. That was the only way to squeeze in all that action. But the concept was really too big for a single show.

BH: “Oh, Brother!” features an interesting concept in which the Mario Bros. have a fight. Did you draw upon any of your own childhood experiences growing up?

PM: Not consciously. I don’t have a brother, but I do have a sister. Like all siblings, we didn’t always get along growing up together, so perhaps that experience filtered into the show. I liked that story because it broke the formula. It wasn’t the usual routine of our heroes running around strange lands, fighting the Koopa. In that episode, the primary conflict was character-based — a silly argument between two brothers getting on each other’s nerves, kind of like The Odd Couple. In the end, Mario and Luigi realize that, despite their differences, they love and need each other. I wish we had done more shows like that. I had a good time writing it.

BH: Do you know why several different voice actors were used for many of the principal characters?

PM: Again, I had no involvement with that part of the production, so I can only speculate. Sometimes actors have scheduling conflicts that cause them to leave a production. Sometimes an actor just doesn’t work out and they replace them — and hope nobody notices!

Perry Martin’s script for “Mario Meets Koop-zilla.” Photo © DIC Entertainment.

BH: You only wrote one episode for Super Mario World. Why only one?

PM: DIC had a very small order for that show. I forget how many episodes, but it was just a handful. They were also in a hurry to get them done, so the process was streamlined. Phil Harnage was the story editor on that one. He wrote all of the premises and assigned them to writers from the original series. The show I did was “Ghosts R Us.” I think we skipped the outline stage and went straight to script — which, by the way, is never a good idea.

Now, I have another funny story about that one. I had a very hard time writing that script. I was really burned out on the Mario Bros. by then. I just had nothing more to say about those characters and their world, so I struggled to write it. I mean, I suffered over every word. I didn’t like what I was doing, and that’s torture for a writer. I slaved over that script and was never happier to get to the end of something in my life. I finished it around 2:00 on a Friday afternoon, and DIC wanted it by end-of-business that day. Now this was before you could send documents by e-mail. Everything had to be delivered by hand.

So I popped a disc into my computer to copy it over — and, to my horror, my software bombed. I lost the entire script. And I hadn’t backed it up either. Well, I wanted to blow my brains out right then and there. Instead, I did the only other thing I could do: I called up DIC and gave them the bad news — that I’d lost the script and would have to write it again. That meant I would miss their deadline, something I’d never done in my life. They were very unhappy, to put it mildly, and I was more upset than they were.

So I took a deep breath, rebooted my computer, and started again, from the beginning. But I soon realized that I’d agonized over that script so much that I’d actually memorized the entire thing! I hammered it out word-for-word exactly as I’d written it before, making a few improvements along the way. It took me about two hours. When I was done, I copied the thing to a disc, drove it over to DIC and dropped it off — just before they closed. So I made my deadline after all. But let me tell you, I learned the hard way how important it is to back up your work!

BH: Believe it or not, Phil Harnage has become something of an Internet cult figure among Nintendo fans in recent years, especially for his work on Super Mario World, which has resulted in numerous online memes. What was it like working with Mr. Harnage?

PM: Phil was a nice guy, very easy-going. Writing cartoons seemed to come naturally to him. He really seemed to enjoy what he was doing. Despite the constant pressure of writing against deadlines, I don’t remember ever seeing him stressed out. I also remember that Phil collected antique wristwatches. Every day, he showed-up wearing a different watch, all of them amazing.

BH: What did you think of the character Oogtar? At time time, I found the character annoying, though my views have softened over the years.

PM: Honestly, I have no memory of that character. To answer your question, I pulled out my script and can see that there’s no Oogtar in it. There is a character named Bartzan, who’s described as “a prehistoric cave kid resembling Bart Simpson” — and that character is also present in the premise Phil Harnage assigned to me. Perhaps the producers decided to go in another direction, again for legal reasons, and directed Phil to rework the character into what ultimately became Oogtar. I suspect that’s what happened, but I can’t say for sure.

BH: Overall, what did you think of the various Mario shows you worked on?

PM: I’m proud of the work that I did on the series, given what it was, but I can’t say that I think highly of the final product. That’s not unusual for a screenwriter. Nothing ever measures up to the show you see in your head when you’re writing it.

Many years ago, before I ever worked in TV, I met Doug Wildley, creator of Jonny Quest, my all-time favorite cartoon. When I told Doug how much I loved it, he frowned and said, “Christ, I wish I felt that way!” To him, that show was one painful compromise and disappointment after another. At the time, I couldn’t understand why he wasn’t prouder of it, but I do today. It’s the same with me and the Super Mario Bros. I’m really glad there are fans who like it, but I can’t watch the thing without cringing.

BH: Was the experience enjoyable?

PM: It was hard work, but I did enjoy it. Writing a dozen episodes of the Super Mario Bros. expanded my view of my own ability. I felt if I could write twelve episodes of that, then I could do just about anything. But I have to say, looking back on it now, that I don’t think I was a good fit for animated TV. I didn’t feel much connection to most of the shows that I worked on, which made writing them even harder than it should have been.

On top of that, I prefer to take my time and put a lot of thought into my work, and that’s not a luxury you have in cartoons. But I liked all of the people at DIC, from Andy Heyward on down. Robby London was always supportive, and Bruce and Reed Shelly were wonderful to me. That was a long time ago and I’ve moved on to other things. Since then, I’ve had a successful career as a DVD producer, and I’m writing and producing my own projects now. But I look back on those days fondly. And it’s really nice to know that there are people out there who remember some of the shows I did, like the Super Mario Bros., and have affection for them. That’s the best reward any writer can get.

When is it from?

LikeLike

This was a really awesome interview! I’m really happy we have new information for the Cartoons. Seeing these model sheets years later is something special. Too bad a lot of animation stuff was destroyed for the Mario Cartoons including stuff like model sheets for other episodes and animation cels. I have well over 200 animation pieces from the Mario Cartoons including some unused stuff in the show. I would really love to ask Perry Martin some question of my own, maybe it would be possible to set something up like a second interview? Also if you have anything about the Cartoons just ask me, I pretty much know everything. Hope you see this and maybe get something set up! Thanks!

LikeLike