The early 1990s saw Tsuburaya Productions, the creators of the long-running Ultraman franchise, bring the hero from M78 all the way to California for his Hollywood makeover. In the process, an aspiring screenwriter named Bud Robertson was tapped to help update Ultraman for a new generation. In total, Mr. Robertson penned three entries in the made-in-the-USA series Ultraman: The Ultimate Hero (1995), namely episode 5 “Monstrous Meltdown,” episode 9 “Tails from the Crypts,” and episode 10 “Deadly Starfish.“ In November 2025, Mr. Robertson answered Brett Homenick’s questions about his considerable contributions to the Ultraman universe.

Brett Homenick: Let’s start at the beginning. What can you tell us about your early life, such as where you grew up and what your interests were?

Bud Robertson: I grew up in San Jose, California, which is technically the south end of Silicon Valley but hardly a mecca for movie production. My father was a finance exec for a number of tech companies over the years, ranging from semiconductor firms to a short-lived video game start-up that made a splash with a game featuring the rock band Journey for the Atari 2600 game console. My mother was a stay-at-home mom who raised four kids and found time to write, and later publish, poetry. From my dad, I inherited discipline and perseverance; from my mother, I inherited whimsy and creativity. The mix has served me well over the years.

I’ve always been surrounded by technology; growing up, we didn’t take family vacations, but we were often the first on the block to have the latest new toys: a projection “big screen” television, a LaserDisc player, a video camera, and a video recorder are a few innovations that come to mind.

Before the technology boom of the ‘80s, I was a regular kid of the ‘70s. I played baseball and soccer, had a newspaper delivery job for a time, and played outside until the streetlights came on. I lived on a cul-de-sac with 22 kids, so afternoons and weekends were spent playing Capture the Flag and other community games. I loved watching the San Francisco Giants and the 49ers. Pretty standard stuff.

I’m the oldest of four, so I always had younger siblings for company. My sister and I are “Irish twins” born less than 12 months apart, so I’ve never known a time as an only child. My extended family was close-knit, with dozens of aunts, uncles, and cousins who gathered whenever possible. As my wife says, it was a Brady Bunch childhood.

BH: What led to your involvement in the film industry?

BR: In my early teen years, I became fascinated with movies. It probably started with Star Wars (1977), which was released the summer I turned 13. From then on, I would ride my bike to the dollar theater where I could see a double bill and sit through the first film twice if it was good and I had time to kill. I didn’t watch a lot of TV, but I certainly spent time at the cinema. I began collecting movie soundtracks at that time and became a huge fan of Jerry Goldsmith, John Williams, and James Horner.

I didn’t realize it at the time, but I was studying films more and more closely, focusing on editing, music, cinematography, and, most importantly, storytelling. In high school, I began outlining what I envisioned to be a science-fiction novel. I spent countless hours – without any training – fleshing out a story I planned to write. In my junior year of high school, that changed.

In English class, I sat next to a guy named John Ottman. In early 1981, I happened to mention that I had just ordered the soundtrack to Battle Beyond the Stars (1980) by James Horner from a mail-order record store – this was long before the days of online shopping. Turned out, John was a soundtrack fan, too. As we talked about movies, he told me he’d actually made a couple already using a Super 8 camera borrowed from a neighbor. We decided to make a sci-fi movie of our own the following summer between our junior and senior years.

We spent the next few months writing Ultimatum together in the afternoons, working part-time jobs to save money for film, sets, costumes, and other necessities. During Easter break – that’s what we used to call it back then – I spent a week with my grandfather, building a four-foot long spaceship model we would use during filming.

We had no idea how big the script we had written was, or how long it would take to film and edit. In June 1983, nearly two years later and months after we had graduated high school, we finally premiered Ultimatum. The high school welcomed us back as pseudo-celebrities – we had used faculty in our cast – and allowed us to use school’s main theater, which was filled to capacity for two back-to-back screenings. I was hooked on movie-making.

John and I went to De Anza College in Cupertino, California, to get our AA degrees with an emphasis in filmmaking. Then, in 1985, I moved to Los Angeles to attend UCLA and earn a BA in film and TV production, while John headed to USC for his film production degree. Although our schools were cross-town rivals, we continued to work on each other’s film projects and remain friends today.

John became a big-league film composer and editor, doing double duty on blockbuster films like X-Men [X2 (2003)] and Superman Returns (2006), among others. John later earned an Academy Award for his editing of Bohemian Rhapsody (2018), a biopic about the rock group Queen.

BH: Please talk about how you were hired to write three episodes of Ultraman: The Ultimate Hero (1995).

BR: While I was finishing my final film at UCLA in 1988, I landed a job in the accounting department of an independent movie production and distribution company called Noble Entertainment Group – I also inherited from my dad a good feel for numbers. Noble produced a bunch of crappy low-budget action films for the international market, such as Pale Blood (1990), Trapper County War (1989), and L.A. Bounty (1989).

Although those films were nothing to write home about, they did give me a very good working knowledge of how films are made, and how the money is spent. UCLA taught me how to make films, but Noble taught me the business of filmmaking. I crunched numbers for Noble while writing spec screenplays at night and submitting them to agents around Hollywood as I tried to get my big break.

At Noble, I worked with Aaron Griffith, who served as internal business affairs but also helped with casting. Like me, he was doing a day job while pursuing his dream of becoming a full-time casting director. And, like me, he dabbled in outside projects. Fortunately, one of them was Ultraman. Aaron knew that I was a fledgling writer; we had unofficially formed a company called Tower Entertainment together with a couple of my UCLA classmates – including Todd Gilbert and Kevin Hudson – in an effort to launch our own production and distribution company. We were attempting to obtain the rights to Speed Racer (1967-68) at the time, long before it became a Hollywood movie.

Although Tower Entertainment never got off the ground, Aaron landed the casting director role for Ultraman, to be produced by King Wilder and his companion Julie Avola. King would also write and direct all 13 episodes for Tsuburaya, the Japanese toy company that was also financing the new series. Kevin Hudson, a UCLA classmate and roommate of mine, was hired to create the Ultraman suit and all the monster costumes. Through them, I was aware that a fun show was “spinning up” right in my backyard.

By January 1993, pre-production for Ultraman was in full swing, and King Wilder realized he would not have time to write all 13 scripts while giving proper attention to casting, production design, location management, and all other critical aspects of filmmaking. With some reluctance, he decided to bring on outside writers, and Aaron recommended me.

I think I must have submitted one of my spec scripts as a sample, but I don’t remember for sure. After a brief interview with King and Julie, I was hired to write the Gabora episode. Quick script delivery on my part and an enthusiastic response from King landed me the Pestar and Aboras/Banila writing assignments.

BH: Were you at all familiar with Ultraman at the time you were hired?

BR: I grew up watching Speed Racer, Kimba the White Lion (1965-66), and other anime programs – before the word “anime” had entered our lexicon. Ultraman (1966-67) was one of those shows I would watch in the afternoons on a local UHF station – for those who remember VHF and UHF channels.

I can’t say I was a connoisseur of the show, but I was familiar with the primary characters and conflicts, and I enjoyed the rubber-suited monster battles. Before 1993, I had no idea there had been multiple iterations or a plan to make the first U.S.-produced version.

BH: You ultimately wrote three episodes, yet Todd Gilbert only wrote one. Do you have any idea why there was a difference?

BR: The answer is pretty simple: schedule. I became part of the Ultraman creative team early on, but production was looming, and there were still scripts to write. In April 1993, I was polishing the drafts of my scripts, and there was still at least one more episode to write, if not more. King was too busy, I was too busy, and principal photography was scheduled to start soon.

I recommended Todd Gilbert for the job. We had been classmates at UCLA, we worked together at Noble at the time, while also working evenings and weekends to secure funding for a feature script he had written. I knew he was a good writer. Todd came in near the tail end of the screenwriting process for Ultraman, or I’m sure he would have written more than a single episode.

BH: Do you have any memories of working with director King Wilder and producer Julie Avola? What were they like?

BR: Julie was producing, and my interactions with her were mostly limited to executing writer contracts and confirming that the scripts and rewrites were being delivered on schedule. I don’t think I had any real creative interaction with Julie, but I liked her on a personal level and was impressed that she had succeeded in doing something I had yet to do: obtain funding for a commercial production.

Most of my interaction was with King, who had a creative vision for the series. Along with Julie, his longtime girlfriend, he had secured the funding and promised to deliver a completed television series that satisfied Tsuburaya. King was soft-spoken and very easy-going, and I really enjoyed working with him. We remained friends and colleagues for many years after the series was released.

King gave good, constructive notes on each draft I submitted. This is about the best you can hope for as a writer; the worst is to get notes like, “This doesn’t work for me.” I always knew what King wanted and how to get there. Luckily, my first drafts were usually pretty much on the mark and did not require wholesale changes.

BH: How were your interactions with Japanese side, Tsuburaya Productions, at the time?

BR: I had no interactions with the Tsuburaya team at all. King was the intermediary through which all scripts were funneled, and he fought for acceptance of his vision as implemented by me. On one or two occasions, King told me that Tsuburaya had rejected part of the script and made certain recommendations, which I needed to follow. But, overall, King absorbed all those blows and made the experience very easy for me.

BH: Did you write the episodes in the same order in which they appear in the series?

BR: I did not write them in final series order. I’m not sure if there was a planned series order while we were in pre-production. If there was, I was not aware of it. The first script I wrote was “Monstrous Meltdown,” which became episode 5. The second script I wrote was “Deadly Starfish,” which became episode 10. The final script I wrote was “Tails from the Crypts,” which became episode 7.

BH: “Monstrous Meltdown” is a remake of “Lightning Operation” from the original Ultraman series. It features the monster Gabora and guest-stars Bill Mumy. Could you talk about writing this episode?

BR: First, let me say that it was a real joy to be writing something that I knew was going to be produced. Other than my student films, I had not had that experience. By 1993, I had written four or five spec features, none of which had gotten traction yet. I had written treatments for another half-dozen films, but none of those had been greenlit either. I had a lot of nice script binders on my bookshelf and no professional writing credits to show for it. Ultraman changed that for me.

The Gabora script – most if not all episode titles were assigned in post-production – was critical for me because it was the first paid writing assignment I’d ever been offered, and I knew it could open the door for more if I delivered a good product.

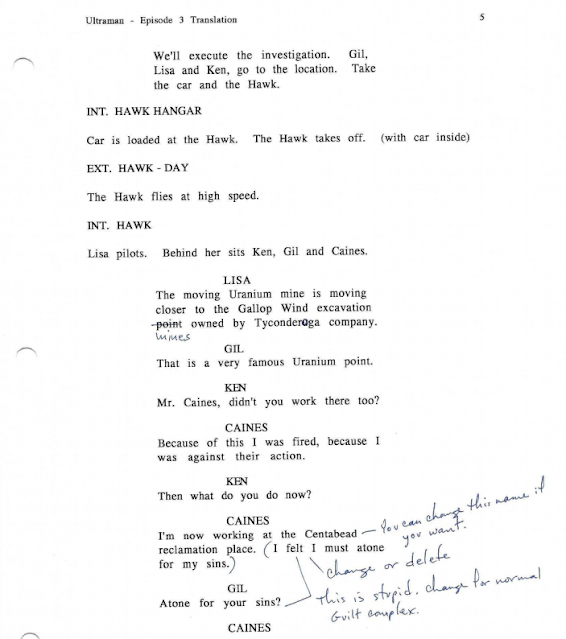

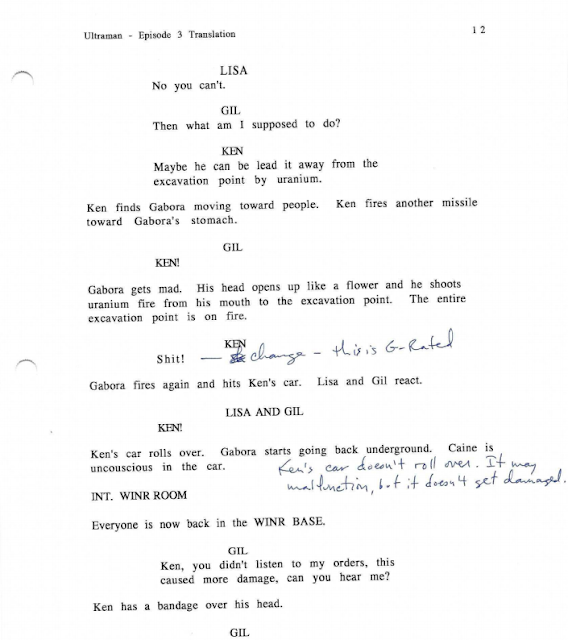

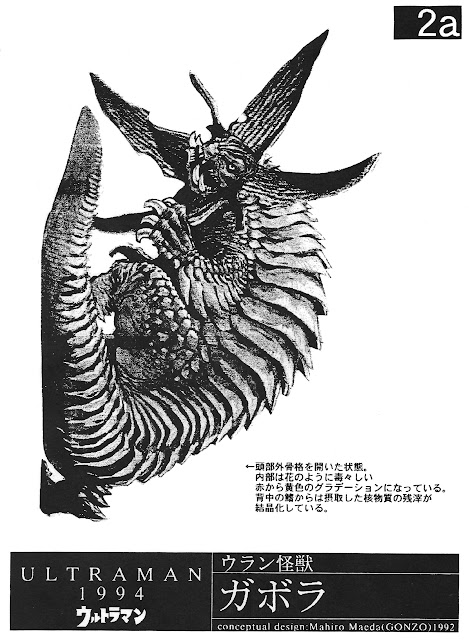

To get me started, I was given an English translation of the old Japanese episode Tsuburaya wanted to remake. I was also given two pages of monster illustrations so I’d know what the creature – and the toy product tie-in – looked like. The literal translation, dated January 9, 1993, had been done by Ken Iyadomi and King Wilder. King had also written notes in the margins to give me additional creative direction. The translated dialogue was stilted, and the story lacked pacing for a then-modern audience – I suppose those scripts are slow by today’s standards.

The first decision I made was that the humans in the story needed to have their own victory. Ultraman would defeat Gabora; that was a given. But people watch television, and people need to see human heroes, too, not just bystanders who applaud the superhero when the monster is dispatched. By creating two story lines with two threats and two sets of heroes, I could cross-cut between them and inject greater tension. It would also allow for compression or expansion of time within the story, one thing that scripts can do with great effect. So that was a conscious decision from the start.

I had great fun writing the script. The character names of the main cast were established already, but guest characters could have any name I wanted. It gave me a chance to give a nods to friends and family. Fenton, the truck driver who gets sucked into the ground in the opening scene, was an ode to my friend Roger Fenton, a UCLA classmate and assistant editor working with John Ottman on big-studio films. Windeler, the boss of the mining company, was named after my college roommate Bob Windeler, a chemical engineer who later garnered a gazillion patents. The name of the Malmori Mining Company was a nod to my all-time favorite low-budget movie, Battle Beyond the Stars, a remake of Seven Samurai (1954), produced by Roger “King of the Bs” Corman.

Since this was my first script for King and Julie’s Major Havoc Entertainment, I didn’t want to stray too far from the translated source script. As agreed, Kazunori Ito got story credit for the source material, and I got sole teleplay credit for adapting his work.

Writers have no input in the casting process, but I was really pleased to learn from Aaron Griffith that Billy Mumy had been cast as Fenton. In addition to watching countless hours of Japanese animation as a kid, I’d watched every episode of Lost in Space (1965-68) many, many times. Having a small connection there still makes me smile.

BH: “Deadly Starfish” is basically another remake – this time of “Oil S.O.S.” [from] Ultraman. It features a character named Mendez, who is a former classmate of Kai’s who at one time almost joined WINR. It’s an interesting premise for an episode. Please discuss your work on this episode.

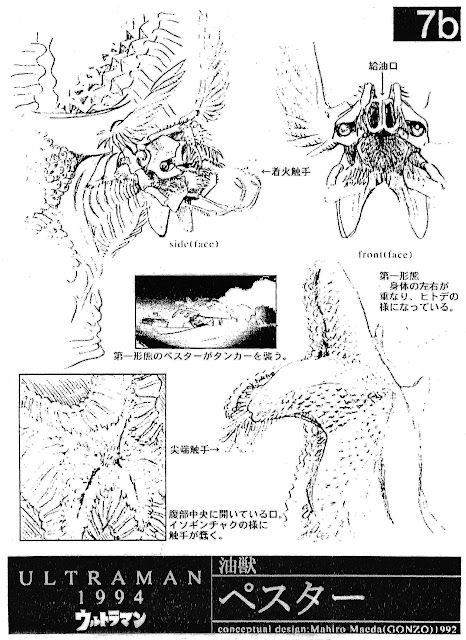

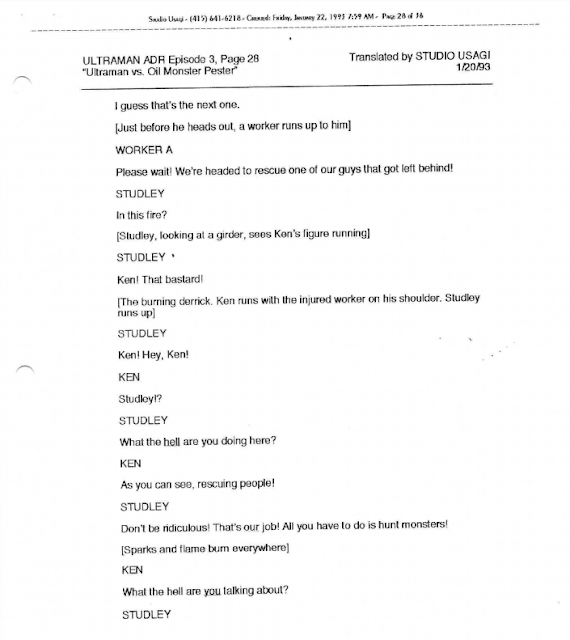

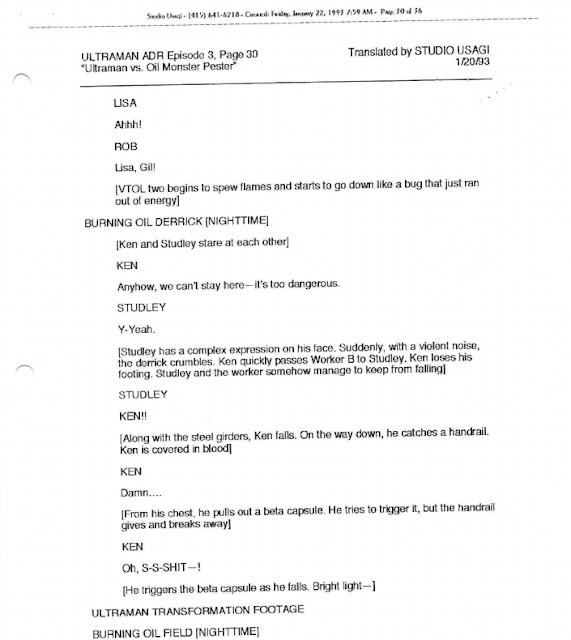

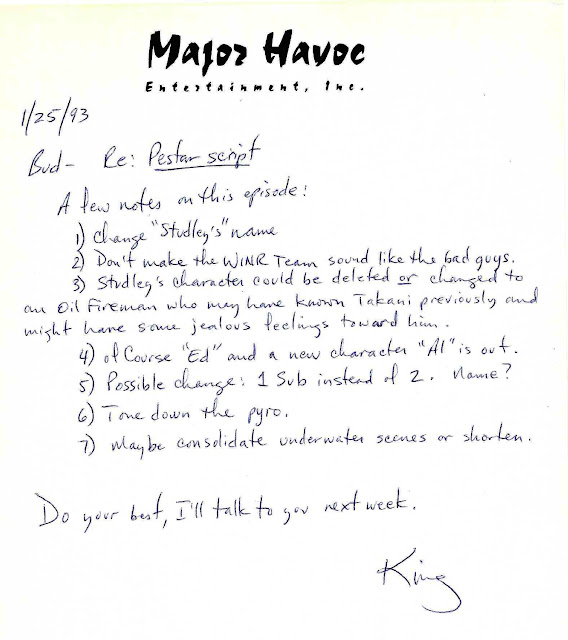

BR: The source translation I received for the Pestar episode was actually an ADR – automated dialogue replacement – script used for the purpose of dubbing the [original] Japanese-language show into English. The ADR script had the title “Ultraman vs. Oil Monster Pester.” Again, I was given two pages of monster illustrations so I’d know what the creature, and the toy product tie-in, looked like. For this episode, I also got a short memo from King with a punch list of changes he wanted me to make, including:

- Don’t make the WINR team sound like the bad guys

- Studley’s character could be deleted or changed to an oil fireman who may have known Takani previously and might have some jealous feelings toward him

- Possible change: 1 sub instead of 2. Name?

- Tone down the pyro

- Maybe consolidate underwater scenes or shorten

King’s note inspired me to create the central tension between Mendez and Kai, and I drew upon a real-life story I’d heard from a friend of the family, Earl Staurseth. Earl had been in the Air Force and dreamed of becoming a pilot, but, when he was found to be colorblind, he was permanently grounded. It always rankled him, and I thought the scenario could serve as good tension in the script.

As with the other Ultraman scripts I wrote, names for guest characters included more personal nods. Garner, the helicopter pilot in the opening scene, was an ode to Michael Garner, one of my other roommates at the time – we dubbed our rental house the “pad-o-guys.” Arturo Mendez, the ABOCO oil refinery manager who serves as the primary guest character in the episode, was named after Mario Arturo Mendez, a UCLA classmate who was my writing partner on several spec feature screenplays and the best man at my wedding three years later. Inspector Datzman at the refinery was named for all the Datzman relatives on my mother’s side of the family who share that surname. The ABOCO company was actually an acronym for Antonio Bay Oil Co., paying homage to John Carpenter’s The Fog (1980), which was set in the small town of Antonio Bay.

One of the things I am also pleased with was my ability to name the Barracuda sub. I had previously named the flying WINR mother ship MAC-2000 in my scripts, with the acronym standing for Mobile Air Command 2000 – a futuristic date at the time – but King had rejected that idea and said the principal characters and vehicles had already been established. So I was happy when he gave me freedom to name the sub. I wanted something fishy and powerful. “Piranha” didn’t sound right, but Barracuda …

Having successfully delivered the Gabora script, I had a lot of freedom with the Pestar script. I was able to create tension with Mendez being grounded, then giving him redemption by jumping into the cockpit to help when the WINR team needed him. I invented an underwater rescue sequence between a sub and an aircraft. And I was able to retain the key Ultraman vs. monster battle required. With three competing story lines, the cross-cutting was fantastic on paper. I could see the show clearly as my fingers flew on the keyboard.

Again, I thought it was very important that the humans had their own objectives and victories. A show where everything is solved by Ultraman – even a show called Ultraman – wouldn’t resonate with the audience if there were no identifiable human heroes. Here, I was able to have the humans perform a daring undersea rescue and also save the oil pipeline while Ultraman dispatched the creature threat. Plenty of heroes to go around!

With the Pestar episode, I knew I had meaningfully changed the original story, enhancing it with fresh elements worthy of shared story credit in my opinion. I approached King with the idea, but he was skeptical that Tsuburaya would approve. After all, the purpose of the television series was to present updated versions of existing stories to rejuvenate flagging toy sales of specific monsters. We weren’t charged with making any substantial changes. But he agreed to fight for it, and, surprisingly, Tsuburaya agreed after reading my draft. In the end, Hiroshi Yamaguchi and I got shared story credit – with me rightfully in second position – and I got sole teleplay credit.

When multiple writers work together on a project, they are credited as a team with an ampersand – “&” – but, when they contribute separately to a project, they are credited as individuals with the word “and.” Since Hiroshi and I never met and did not work as a team, we are correctly credited as “Hiroshi Yamaguchi and Bud Robertson.”

BH: “Tails from the Crypts” is essentially a remake of “The Demons Rise Again” [from] the original Ultraman. This episode features the monsters Banila and Aboras. What can you tell us about working on this episode?

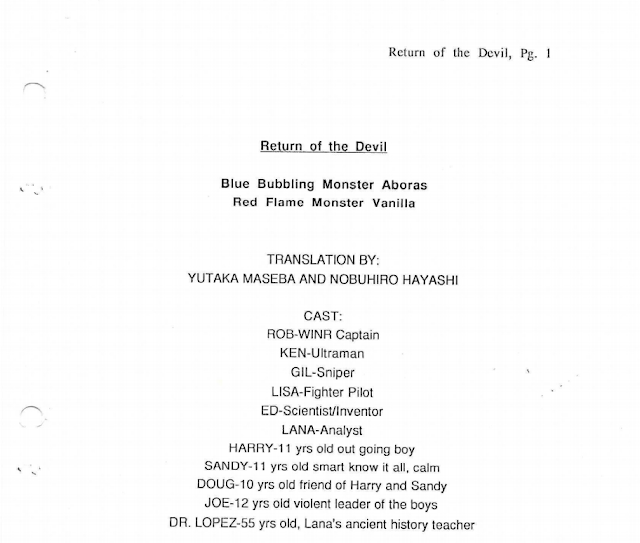

BR: The English-translated script I was provided had the title “Return of the Devil” and featured two monsters – “Blue Bubbling Monster Aboras” and “Red Flame Monster Vanilla.” I was really able to play with cross-cutting in the script, moving between each of the two monsters, as well as humans working to overcome their own perils. It was ideal for creating tension on paper, which results in tension onscreen if the editor follows my blueprint. As with the Gabora episode, I was also given monster illustrations so I’d know what the creatures, and the toy product tie-ins, looked like.

Names for guest characters in this script included more personal nods. Karen and Dennis, the main intrepid explorers, were named after my sister and her husband. McCarry, the water department technician in the scene where the second sarcophagus is discovered, was named after a good high-school friend, Brian McCarry. And Dr. Whitaker, the expert in ancient civilizations – and Beck’s former instructor – was named after Jason Whitaker, a co-worker of mine in San Jose who also aspired to be a filmmaker.

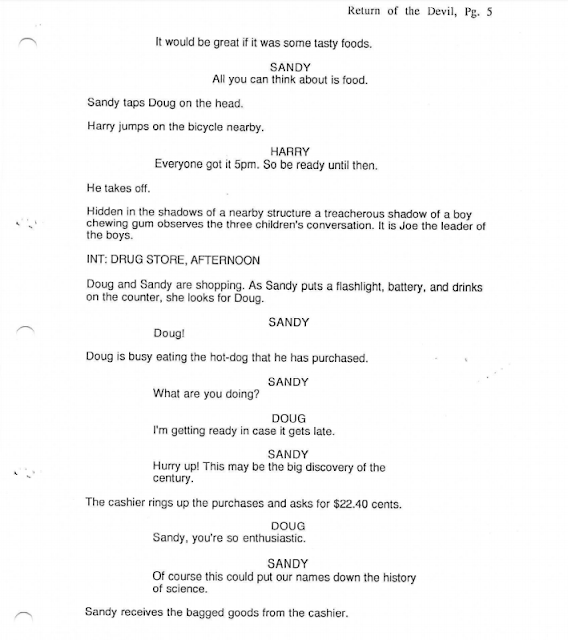

In the translated source script, the duo of Karen and Dennis had been four younger kids who bantered about food and other innocuous subjects. Although they took necessary actions to move the story forward, all their dialogue was boring banter that did little but kill screen time. Almost everything revolved around food, what kind, how much it cost, and why one kid ate too much of it.

I tossed all that dialogue away and created new characters who could trigger the same essential actions. To motivate the characters, I came up with the school-reporter angle and made them high-school age. I reduced the number of kids from four to two – the bare minimum required for dialogue. Fewer characters meant more time devoted to each one, giving me a chance to flesh them out a little bit rather than leaving them as cardboard cutouts.

The use of sound as a trigger for opening the sarcophaguses was in the original, but I was able to tie the school-reporter/photo-journalist angle into [the] main story line by incorporating the high-pitched whine of the flash charging with the unleashing of the monster. To me, finding ways to make actions integral with character is always more interesting and effective. Hopefully, Karen and Dennis were fun to watch as they became cause and effect in the adventure.

Again, I was very conscious to make sure that the human characters had their own challenge and resolution while Ultraman battled the creatures. In this case, Ultraman was outnumbered, and the WINR team was able to provide the necessary distraction that gave our superhero the upper hand.

Although I reinvented characters and thoroughly replaced all meaningful dialogue, I did not feel I had changed the story enough to fight for a story credit. Accordingly, Hiroshi Yamaguchi retained sole story credit and I was given sole teleplay credit for adapting his original work.

BH: How much freedom did you have in writing the scripts?

BR: King Wilder gave me a lot of free rein, and I never had any direction or interaction from Tsuburaya. However, I was aware of the boundaries of the assignment in creating a renewed market for toys whose sales had waned over the years. The stories I wrote needed to promote Ultraman and four specific monsters in entertaining ways that would drive merchandising. The key word for me was “entertaining.” I wanted to write episodes with exciting action and amusing dialogue, with character arcs where I could squeeze them in and as much accurate science as possible in the age before the Internet.

King gave me those translated sources as guides, along with a few monster illustrations, and told me to run with them. Cautious at first, I did not stray far from the original story. I replaced dialogue at will, but, since my source was, at times, an awkward translation, there was no worry about that. I played it somewhat safe with the Gabora script.

Then, as I proved myself to King and Julie, and as my confidence increased, I dared to replace more source material with original material in the service of what I hoped would be superior stories. King’s director notes were always constructive and gave me room to address them however I saw fit, which was really a writer’s dream.

BH: How many drafts of each script did you write, as best as you can remember?

BR: Overall, I wrote four drafts of the Gabora script. I was asked to return the first draft within two weeks; if I couldn’t meet the production deadline, I wouldn’t be of any value to them. I got the 23-page draft finished in a week and submitted it on January 20, 1993. I addressed creative notes in a second draft on January 25, 1993, and in a third draft on February 11, 1993 – just days after I submitted my first draft of the Pestar script.

As commencement of production neared, I was given a few final production notes to address in late March. On April 4, 1993, I delivered the final shooting script.

I wrote three drafts of the Pestar script. About a week and a half after I received my second assignment from King with high-level notes dated January 25, 1993, I delivered the first draft on February 7, 1993. King accepted my first draft script virtually as written, even though I had made significant changes to the translation source. My second draft with minor tweaks was delivered four days later, on February 11, 1993. Production notes were addressed in a final shooting script, which I delivered on April 4, 1993, the same day I delivered the final shooting script of the Gabora episode.

I wrote three drafts of the Aboras/Banila script. The first draft was submitted on February 21, 1993, about a week after I received this last assignment from King. I addressed creative notes in a second draft two days later, on February 23, 1993. Final production notes were addressed in a final draft, which I submitted on March 29, 1993. Although this was the last script assignment, it was the first of mine to be finalized.

BH: How long did it take to write each script, as you recall?

BR: On average, each first draft took me about ten days to write. Revisions generally took about half that long, depending on how much else was going on with my life at that moment. I was working a full-time day job at Noble Entertainment Group, but I was single and not dating anyone at the time, so my evenings and weekends were completely free. I’ve always been a night owl, so I often wrote until one or two in the morning.

BH: Did you have any ideas for your episodes or the other monsters that weren’t used in the series?

BR: Not really, no. It wasn’t that sort of project. The monsters and story lines were reasonably well-developed before they were given to me, and my assignment was to update and enhance the source material. With my film production accounting background, I understood the necessity of keeping the story within budget. It would have been easy to write bigger scenes. A line of description as simple as, “All hell breaks loose,” could blow the entire budget. I knew we could not afford additional monster costumes. I knew we needed to keep the practical effects minimal and targeted for best effect. I knew to stay in my lane, and I was fine with that.

Frankly, I enjoyed working within those parameters because they challenged me to be creative toward a purpose.

I hoped that Tsuburaya would ultimately greenlight a second season where I could be central to the writing team from the start, possibly influencing story and monster choices. But that was a downstream aspiration I kept inside, one that never materialized.

BH: What was the most difficult part of writing the scripts?

BR: For me, these stories just flowed. I had spent five years writing spec feature screenplays and honing my craft, so writing 23-page teleplays was like authoring short stories after battling longform novels. I honestly don’t remember any “difficulties” in the screenwriting. I only remember the joy of creation, knowing that my words were forming the blueprint of shows that would actually be filmed and seen by a global audience.

BH: What did you think of the finished product?

BR: In general, I found the episodes to be a lot of fun. They were good representations of what I had put on paper. Of course, certain effects showed budget limitations. Some of the miniatures left a bit to be desired, but there were a lot of them and I don’t blame the effects crew at all; they had an impossible assignment.

I found some of the acting to be a bit stilted at times, too, but that’s a function of a young cast and a rapid shooting schedule. As Roger Corman would say, “How long to get it great, how long to get it good, and how long to get an image?” Sometimes you have to sacrifice art and performance for schedule. But, overall, the characters were engaging, the action was entertaining, and the show brought new life to aging toys.

BH: Was there any feedback from Tsuburaya Productions?

BR: I never heard anything directly from them, but the sense I got from King, and from how the show was treated, is that Tsuburaya was a bit disappointed. I’m not sure what they were expecting for the marginal budget they provided. Perhaps their unfamiliarity with wages of U.S. film crews gave them unreasonable expectations. In any case, I learned fairly quickly after the shows were completed that Tsuburaya intended to release them in Japan but not in America. This was a disappointment, as I hoped to share my first screen credits with friends and family.

Eventually, the episodes showed up on YouTube, but the enthusiasm and energy had dissipated by then.

BH: Did you ever get to meet the cast or crew? If so, please tell us about it.

BR: I was working a full-time job while the show was in production. If I remember correctly, I was offered a production job, probably as a production assistant or maybe second assistant director since I was new to professional filmmaking at the time. But I couldn’t leave a permanent job to work freelance for a couple months, so I passed.

I did visit the Ultraman set one day during filming of the Pestar episode. It was great to see the full-sized Barracuda sub in action, with Harrison Page, Rob Roy Fitzgerald, and Robyn Bliley performing lines I had dreamed up. In the age before cell phones, I wasn’t able to shoot any photos with me on set or with the cast.

Coincidentally, six years later, I would serve as first assistant director on Route 666 (2001), a feature film in which Rob Roy Fitzgerald played a supporting role.

One of my roommates at the time was Kevin Hudson, who created the Ultraman suit and all the monster costumes. He also supervised all the filming on set for the monster battles. On a daily basis, I talked to Kevin about the challenges he was facing and the solutions he had come up with.

When it came time to shoot the monster battles in the parking lot of a shuttered restaurant on a hilltop in Burbank, California, I had to come see the fun for myself. It was a really hot day – August, I think. The guys in the suits were roasting, but they had to perform all their acrobatic moves, anyway. In the end, I think King got everything he wanted, and certainly everything he needed to cut the shows together.

Other than my interactions with King and Julie, and my friendships with Aaron Griffith, Kevin Hudson, and Todd Gilbert, I never really encountered any of the cast or other crew.

BH: Of the three episodes you wrote, which one is your favorite?

BR: Pestar is my favorite, partly because it has the most original material of mine in it, and partly because I pushed for and received a story credit. Beyond that, I think it’s just the most entertaining overall. The undersea water rescue was my favorite sequence of them all.

BH: Overall, what did you think about working on Ultraman: The Ultimate Hero?

BR: Working on Ultraman was a key experience in my filmmaking career. I would go on to write a few produced feature screenplays and television documentaries, but Ultraman was the first time I was paid to write. You always remember your first, right? Every night sitting down at my computer to fill blank pages with images and dialogue I knew would be filmed was really a joyful experience for me, and King’s easygoing direction and enthusiastic reception of my teleplays was really rewarding. I’m happy to have contributed a little bit to the Ultraman universe!