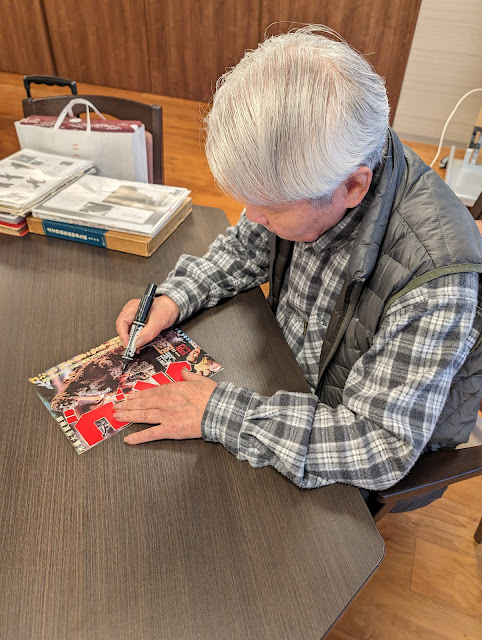

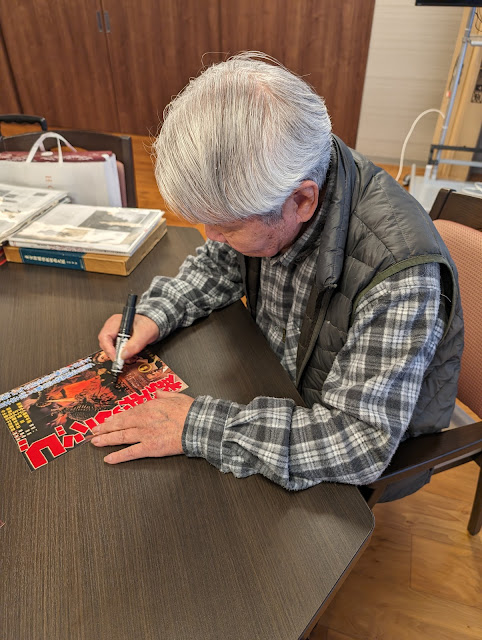

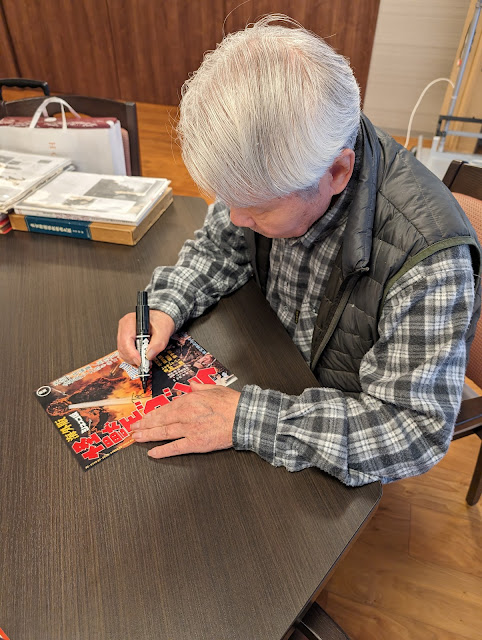

While a privileged few, such as Ishiro Honda and Eiji Tsuburaya, usually receive credit as being the authentic creators of Godzilla, it’s literally true in the case of Yoshio Suzuki. Hired on a part-time basis to help build the original Godzilla suit in 1954, Mr. Suzuki was one of just five modelers who brought cinema’s undisputed King of the Monsters to life in his first film. In the late 1950s, after working on a variety of other kaiju suits, Mr. Suzuki became a camera assistant at Toho before joining the studio’s art department in 1961. In 1968, Mr. Suzuki ultimately became an art director on the Tsuburaya Productions TV series Mighty Jack. The mid-1980s saw Mr. Suzuki travel to North Korea to work on Pulgasari (1985), one of Asia’s most fascinating, and mysterious, kaiju epics. In March 2024, Mr. Suzuki, joined by his wife Mitsuyo, answered Brett Homenick’s questions in an interview translated by Maho Harada.

Brett Homenick: For the record, could you tell us your exact birth date?

Yoshio Suzuki: My date of birth is June 17, 1935.

BH: Where were you born?

YS: I was born in Meguro Ward, Tokyo.

BH: During your childhood, what were your hobbies and interests?

YS: When I was little, I was a bit rough. I got into fights, climbed trees, and swam in the river. I never drew pictures in elementary school.

BH: Could you share some of your memories of the war? What were some of the hardships during that time?

YS: I was a child during World War II. When I was in the third grade, there was an air raid by the Americans. They dropped bombs all over Tokyo. My elementary school was in Tokyo, so the entire school, including the teachers, evacuated to Shirakawa in Fukushima Prefecture. We stayed there for about one year.

BH: Why did you decide to attend Tama Art University?

YS: When I was 19, I decided to go to art school because I was a bad student. I wasn’t very smart. (laughs) My teacher said, “You’re not good at math or science, but you can draw, so why don’t you go to art school?” So I went to Tama Art University.

BH: How did you get hired to work on Godzilla (1954)?

YS: Planning for Godzilla started when I was 19. I was in my first year at Tama Art University, where I was learning how to draw. But I didn’t have money, so I wanted to work part-time. My classmate, Yoshio Tsuburaya, was a friend. He said, “My uncle is going to make a Godzilla movie at Toho; you should work for him.” Tama Art University is in Kaminoge, Setagaya Ward, and Toho Studios is also in Setagaya Ward, in Kinuta.

It was only five or six kilometers between my school and Toho, so I borrowed a bicycle and used it to commute to the studio. At the time, the studio was very popular, and a lot of people went to watch their movies. So there were a lot of people who wanted to see the shoots. There were five guards to prevent people from entering the studio. I showed a piece of paper I had and said, “I’m here to see Mr. Tsuburaya.”

Mr. Tsuburaya was at the studio in Uzumasa, Kyoto, but Toho requested him to come make the Godzilla movie, which required special skills. So Mr. Tsuburaya came from Kyoto, wearing a worn-out suit. He came by bicycle to Toho, and his bicycle was also shabby. That’s when we met.

I was 19 – I don’t know how old Mr. Tsuburaya was then. To shoot Godzilla, he needed to make a Godzilla suit. But it was confidential at the time, so he couldn’t make it at Toho. There was a small studio about one kilometer from Toho. That’s where he was making the Godzilla suit. I was told to go to this studio and help. That’s the first time I saw Godzilla. I was 19 then, so I don’t know how many years ago it was. Many decades ago – maybe 70 years ago?

BH: When you were hired, what did you think of Godzilla as a movie? Did you think Godzilla could be a big hit, or not?

YS: I don’t think anyone expected it to be such a big hit. It was the first time anyone was making this kind of movie, so no one really knew what to expect.

BH: Please describe your work on the Godzilla suit.

YS: The Godzilla suit was made rather primitively. There’s a picture here. To make the Godzilla suit – way back when, we used to have haunted houses, and there were people who made the ghosts and monsters for those haunted houses. The Yagi brothers [Kanju and Yasuei Yagi] were these old men who were 55 or 60, and a designer named Mr. [Teizo] Toshimitsu, who was about 50, and Cho [Eizo] Kaimai, who gathered the material for the suit and did all the negotiations. The four of them were making the suit.

Mr. Tsuburaya asked me to join this team as a part-timer. I was what you would call an underling. That’s how it all started, when I was 19. And I continued working for Toho until I retired. I worked at the studio for 40 years. Eventually, there were fewer and fewer people who watched movies, so they shifted to TV. There were fewer people who went to the theater, so there was less work at Toho. They said, “Mr. Suzuki, there isn’t much work for you here, so you should go to North Korea.” I asked them what I would do in North Korea.

No one wanted to go there because there had been all these abductions [of Japanese people by North Korea]. Apparently, some North Koreans came to meet with Toho executives and said, “Here’s some money. We want to make a movie like Godzilla.” Toho refused many times, but the North Koreans stacked American bills on the table, so the executives drooled and said, “We’ll think about it.” They wondered if anyone would agree to go to North Korea. They said, “Suzuki is an idiot; maybe he’ll go.” They asked me to go, so I went.

In the beginning, all I did was research. What is North Korea like? What is the studio like? What are the people who make movies like? I went alone to find this out. I think I was there for about two months. I was paid quite well. Prime Minister Kim Il Sung had many vacation homes. They told me to use one of them that Kim Il Sung wasn’t using. That’s where I stayed. It was a vacation home, so it was a nice building with a big garden.

At the gate, there were soldiers with bayonets so I couldn’t escape. At night, they let the German Shepherds loose and told me not to go out. They didn’t want me to escape. But they served me expensive food and drinks. It was the prime minister’s vacation home, after all. So I studied a lot there and had many discussions with people who were interested in making a Godzilla movie.

BH: What was the color of the original Godzilla suit?

YS: It was the same kind of color. It wasn’t that different in color.

BH: There are several rumors about how Godzilla got its name. Do you know the true origin?

YS: I don’t really know, but I heard that the producer, Yuko [Tomoyuki] Tanaka, gave it its name. I don’t really remember, but I’m sure there are books that talk about the origin of the name, so maybe you can look it up.

BH: It’s been said that the holes in the Godzilla suit around the neck are supposed to be gills. Is this accurate?

YS: No, no, those weren’t gills. (laughs) They were for the suit actor who would wear the suit and move around. Those holes in Godzilla’s neck are where the suit actor’s head is so he can see what’s going on. The neck is where the actor can look out from. That’s why the neck looks long. They’re not gills or anything!

BH: With whom did you work while working on Godzilla?

YS: I worked with a designer named Mr. Toshimitsu and the Yagi brothers, two old men who were plastic arts technicians. They used to make ghosts and monsters for haunted houses. There was one more person called Cho [Eizo] Kaimai, who was the negotiator and got us the materials. He negotiated with the director and producers. There were four people on the team, and then I joined, so there were five of us making the Godzilla suit.

BH: Do you have any memories of Eiji Tsuburaya during this time?

YS: Mr. Tsuburaya was a very kind director. I worked with him for a long time. I knew him for a long time. He taught me a lot. He was a very quiet director and didn’t yell like Akira Kurosawa. If he didn’t like something, he would just leave. (laughs) He would tell the assistant director what he wanted and just leave. He would go to the editing room and edit. He never yelled at anyone.

BH: How long did you have to work on Godzilla?

YS: Maybe two and a half to three months. It was all trial and error. We had to change the material and change how we made the suit. That’s why it took around three months.

BH: Was that unusual?

YS: It was the first time this was being done, so no one knew what kind of material to use. We used one type of material, which seemed to work at first. But, if it was worn for a long time, cracks would appear, so we wouldn’t be able to use it anymore. So it took us three months because we had to do everything by trial and error.

BH: What other memories from the original Godzilla could you share?

YS: It was the first time a Godzilla movie was being made, so it was a new experience for everyone. And none of us had ever worked on a movie, either, so it was a good learning experience. We didn’t know what kind of material to use for Godzilla.

Mr. Kaimai went all over town looking for the right material, and I went with him. We didn’t know what material to use or how to make the suit, so we learned a lot. The whole team worked together by trial and error to make the suit.

BH: How did you get hired to work on Godzilla Raids Again (1955)?

YS: I’d already worked on Godzilla, so they asked me right away to work on Raids Again. I was still a student, so I went back to school after my part-time job [on Godzilla]. I wasn’t really studying – more like having fun. (laughs) But I was back at school. When they wanted me to come back to work, they called me. Actually, they sent me a telegram that said, “We’re making another Godzilla, come work for us again.” In the end, I worked at Toho more than than I went to school.

I was in art school, in the sculpture department, so I made sculptures. At art school, the professors only came once a week. They weren’t on campus full-time. I had four professors, who were all famous. They came once a week and were only there for an hour, an hour and a half at most. So I went to school when the professors were there. The girls in the administration office told me when they would be there.

I gave the girls in the administration office fruits, sweets, and movie tickets so they would give me this information. They would tell me the date and time when the professor would be on campus, so I would go to the sculpture room and stand in front of a sculpture that a friend had made for me to present as my own work. The professor would give me feedback, saying, “This part isn’t very good. This part is very good,” and then leave. When the professor left, I left. That’s how I graduated.

There were classes like Introduction to Art that I was supposed to attend, but they were held in large classrooms. There were also exams, but they were also held in large classrooms. My friends helped me, so I copied their answers. I always sat next to the smart kids and gave them movie tickets and all sorts of gifts, so they were happy to help me. I got pretty good grades in the end! (laughs)

BH: Next, please talk about making Angilas.

YS: Unlike Godzilla, Angilas had many horns and walked on four legs. The work was quite different from Godzilla. Again, we had to do everything by trial and error to make Angilas. But I really enjoyed the work.

BH: You were working part-time to make Angilas. Was it the same staff as before? Mr. Toshimitsu, Mr. Kaimai…

YS: Yes, and the old Yagi brothers. I was a part-timer, but I wasn’t going to school, so I was there full-time. My friends covered for me, and I only went when the professors were on campus. So I was at Toho full-time. The girls in administration took attendance, and I gave them lots of movie tickets and sweets, so they always made sure to mark me as being in class. I was a very good student, but I was never there! (laughs)

BH: How was the production schedule for Godzilla Raids Again compared to the original Godzilla?

YS: By [the end of] Godzilla Raids Again, I was used to the work because I had done Godzilla and Angilas. So it didn’t take me very long to make the suit. But the techniques for the shoots had evolved quite a bit since the first Godzilla, like using telephoto lenses and high-speed cameras. They used high-speed cameras that shot at four times the normal frame rate, so the risk for mishaps was higher. There was a high-quality American camera called the Mitchell, but there were some mishaps, like the film’s breaking.

Film was very precious because it was imported from the U.S., so there wasn’t a lot of it. Normally, there are 24 frames per second, but, for tokusatsu, they use high-speed cameras and lots of film. It cost quite a lot of money for Toho. They had to buy it from the U.S. because it wasn’t being made in Japan yet. Well, actually, they did make film in Japan, but it wasn’t as accurate as American film, so the image quality wasn’t as good. That’s why they used American film for the shoots.

And, because they shot with high-speed cameras, they used lots of film, which cost Toho a lot of money. And they had no idea if the movie was going to be a hit. But Mr. Tsuburaya didn’t care. If it wasn’t a hit, he would just go back to Kyoto. (laughs)

BH: How long did you have to work on Godzilla Raids Again?

YS: For Godzilla Raids Again, we were used to the work, so it took us half the amount of time, or maybe 70% of the time it took us to make Godzilla. We worked a lot more quickly.

BH: Do you have any other Raids Again memories you could share?

YS: There are a lot of mishaps in tokusatsu because the cameras are filming at four times the usual speed. In addition to the Mitchell, we used other high-speed cameras, but they were all American. No matter which camera we used, many mishaps took place, like the film’s getting stuck, or the film’s breaking. That kind of thing happened often, so they wasted a lot of expensive film.

In the beginning, I worked on Godzilla suits for about one and a half years, and then I became an assistant cameraman. I first worked on Godzilla suits, but then I became seasoned at my job, and I wanted to be an assistant cameraman, and Mr. Tsuburaya agreed. So I started at the bottom again. Here’s the photo. This is Mr. [Sadamasa] Arikawa and Mr. [Yoichi] Manoda, the chief [assistant] cameraman.

BH: Was this for Godzilla Raids Again?

YS: Yes. This [other] photo was taken in North Korea.

BH: [Was this for] Pulgasari (1985)?

YS: Yes, I was a cameraman by then. I was the cameraman, and I made the kaiju. I did both! (laughs)

This photo was taken in North Korea. These are the North Korean crew members – the lighting crew and assistant cameramen.

BH: What are some of your memories of working with Teizo Toshimitsu?

YS: Mr. Toshimitsu was very gentle and kind. He was a sculptor. I worked with him for about two and a half years. I have a photo of him somewhere.

Mr. Toshimitsu was a sculptor. Mr. Tsuburaya had worked with him in Uzumasa, Kyoto, and asked him to join the Godzilla team. It was also the first time for Mr. Toshimitsu to make Godzilla. The suit had to withstand everything, like harsh lighting, rain, rocks – it had to be durable. It wasn’t just about the appearance of the suit, the material, or how it fit the actor; it had to be durable. So I think Mr. Toshimitsu did a lot of trial and error, as well.

BH: How was the relationship between Mr. Tsuburaya and Mr. Toshimitsu?

YS: Mr. Tsuburaya and Mr. Toshimitsu had known each other for a long time. Mr.

Tsuburaya was a cameraman, but Mr. Toshimitsu was more involved in the artistic side, making suits and designing sets and props.

BH: Around this time, what do you remember about working with Sadamasa Arikawa?

YS: Mr. Arikawa used to be a jet fighter. At the end of the war, he trained in the Special Attack Corps [kamikaze squad]. He thought he was going to die soon afterward, but the war ended, and he was saved. He was a pilot, so he knew a lot, like math and technology. So he understood cameras and equipment very well.

BH: How about the Yagi brothers?

YS: As you can see in the photos, they were very old. I think they were over 55. They used to make ghosts and monsters for haunted houses. All those ghosts and monsters move, so they were asked to join the Godzilla team. They were asked to join because of their knowledge of how to make these kinds of things. They were very nice people.

BH: What suit-making techniques did you learn around this time?

YS: A lot of people ask me about suit-making. I think I’ve talked about it ten times. First, they’re worn by actors. These actors tend to be big and strong and have a lot of endurance. We make the suit using the actor as a model, using wires to make the shape. We attach cloth to the wires, then paper. We put on many layers to strengthen it. Then we put on latex and then a kind of malleable plastic. That’s how we made Godzilla.

BH: Around 1957, new Godzilla and Angilas suits were created for an American movie called “The Volcano Monsters.” Since the movie was never produced, there is very little information about these suits in the U.S. What are your memories of these monster suits and the production of this American film?

YS: [Looking at a photo] This is Mr. Toshimitsu, and these are the old Yagi brothers. This is Mr. Kaimai. The one holding the camera is the younger Yagi brother. The five of us made the suit.

We made a new suit to send to the U.S. We received an order from the U.S. to make a suit. It had to be big enough for an American actor to wear, so we had to make it bigger than usual. It wasn’t that difficult because we already had experience making a Godzilla suit.

BH: An American [Bob Burns] who saw the Godzilla suit after they were sent to America in 1957 said that the suit looked like it was in bad condition. He said it looked like many explosives had been used on the suit. Could you comment on his memory?

YS: I never met this American, but I guess he didn’t like the suit. It didn’t meet his expectations. I never met him, so I can’t comment about him. What I can say, though, is that, whenever we made suits in Japan, the actor would say, “There’s no way I can get into that suit!” and we would argue. We said, “This is the only thing we can make, so you have to make do with it. If you can’t get into it, don’t use it!” (laughs) Of course, we didn’t talk to the actor like that, but that’s what we thought. We thought, “If you can’t get into it, then find an actor who can.”

We couldn’t really make another one, and there wasn’t enough time, anyway. But every time the actor would yell at us. I was still a student then, but the others were a lot older, and the actor couldn’t yell at them. So the actor would yell at me and say, “What are you, an idiot? Why did you make this stupid suit? I can’t do my job!” And they would punch the suit. I was standing right next to it because I was supposed to help them put it on, so I got punched.

BH: How heavy was the suit?

YS: Quite heavy. Even if a strong guy wore it, he couldn’t really move. We thought about the material and made another one with a different material so it would be lighter. The first one was heavy, and the movement wasn’t smooth. But, if it were too light, it wouldn’t look right because the actor would be able to move too easily. You needed a certain weight, so it was difficult to find the right balance. We ended up using a lot of different materials for the suit.

BH: Did you work on Rodan (1956)?

YS: I made the Rodan suit, too. It was similar to Godzilla, but it had to fly – or it was supposed to fly. They suspended it with very strong strings [wires], which had to be invisible, but it was difficult to make it look like it was flying. So they used string that was almost invisible and had to erase it in post-production, which took a lot of time and cost a lot of money.

BH: Were you still a part-timer for Rodan?

YS: By Rodan, I was a pro. (laughs) There wasn’t enough staff, so everyone was promoted. I was paid better, so I was more arrogant! (laughs) I got punched a lot in the beginning.

BH: Why did you become a photography assistant in 1959?

YS: I thought it would be cooler to be a cameraman compared to making suits and getting punched by the suit actor. So I told Mr. Tsuburaya that I wanted to be an assistant cameraman! (laughs) I had known him for a long time, so he said, “Sure.” I didn’t have to take a test or anything and became an assistant cameraman right away.

So I became an assistant cameraman, but all I did in the beginning was clean the camera cords and legs. I was the underling of the underlings. There was a wide range of assistant cameramen. You had to wait for five years before you were allowed to use the camera. You had to do your time and gain experience. After five years or more, you could be a cameraman.

BH: What do you remember about working on Monkey Sun (1959)?

YS: For Monkey Sun, I was an assistant cameraman, but, after that, I worked in the art department.

It was always the same for these shoots. As an assistant cameraman, my job was to make sure there were no mishaps with the cameras. We would first watch the rushes after the shoot in the screening room so we could edit out the bad parts. We wouldn’t show them to the director or anyone else because they would yell at us. We would call the development team and ask them if the film was all right. The development technicians would tell us if the focus was off, or if the lighting wasn’t good for a certain scene.

We would then go to the development room so they could cut out of the bad parts. Then we would show the good parts in the screening room. That way, we wouldn’t get yelled at. So we worked very closely with the development team. It was nerve-racking to be an assistant cameraman. It was hard work!

The cameraman looks through the lens and decides if the image matches the scene, but the assistants have to do everything else. The chief [assistant] cameraman checks the lighting, and the next assistant checks the focus and the film to make sure it’s good and loads it into the camera. The most junior assistant cleans the camera cords, the lens, and the tripod, and makes sure they’re ready.

There were four people working [on the camera crew]: the chief [assistant] cameraman, the second, and third assistants. For some movies, there may be two more assistants, so there are six people on one camera.

The most junior assistant always gets punched and yelled at. You had to endure that kind of behavior to make your way to the top. That’s what it was like back then. People got punched all the time. The war had just ended, so everyone was used to being punched! (laughs) It was like being a soldier.

BH: Please describe your work on The Three Treasures (1959).

YS: The Three Treasures was different from the other movies I had worked on. Many of the shots were much larger in scale. The company [Toho] spent a lot of money to make this movie. We spent a lot of time and money to take shots that were difficult to shoot. I remember that everyone worked hard to make this movie.

BH: Do you remember any episodes from The Three Treasures?

YS: I remember that there were mishaps with the camera. The shots we had taken weren’t good, like the images were out of focus, or there were scratches in the images. There were many mishaps like that. For tokusatsu, we usually used three cameras to prevent these kinds of mishaps.

Depending on the movie, we used four cameras. But there were still times when things went wrong. That’s why people considered tokusatsu be a money-eater, which Toho didn’t like. But a lot of people came to watch movies like Godzilla, which meant they made tons of money. They would drool when that happened and decide to make another tokusatsu movie.

BH: Please share your memories of working on I Bombed Pearl Harbor (1960).

YS: I was involved in this movie but didn’t do much. The movie was about airplanes, which meant that they used a lot of miniatures. The biggest miniature plane was about one and a half meters, and the smaller ones were quite small. We used the smaller ones to shoot scenes of planes flying in formation, and the bigger ones for close-up shots. They also made a real plane, but it was just the cockpit, which was only three meters long.

We set the camera and moved the plane itself to take close-up shots. For the wide shots, we used the smaller miniatures. Then we connected the shots in editing. The shots were only three to four seconds long, and we showed one shot after another so the audience wouldn’t notice. Longer shots – for example, of an actor’s bleeding – were shot separately. That’s what we did in tokusatsu – we shot a lot of short shots that were shown one after the other.

BH: After that, you became an assistant in the art department. Please talk about this change.

YS: It was tough to be a cameraman because it was such hard work. The director would say all sorts of things to the cameraman, like, “This image is too dark,” or, “There’s a scratch in this shot.”

Back then, we didn’t have good cameras. We only had Mitchells that were second-hand cameras from the U.S. that we repaired and maintained so that we could use them. That’s why mishaps happened. It’s fine for shooting 24 frames, but, for tokusatsu, we were shooting at four times the normal frame rate, at high speed.

Let’s say we’re shooting Godzilla, and he’s walking very slowly. We’re shooting at four times the normal frame rate, which means we’re using four times as much film, so that’s 96 frames. It costs a lot of money, and you need to have the right techniques. If you make a mistake, you waste a lot of film and money. So tokusatsu was said to be a money-eater.

BH: I understand that Eiji Tsuburaya personally selected you to work on Mighty Jack (1968). Please tell us what happened.

YS: This was a TV [series], which were different from movies. Unlike now, back then it was a lot of work. By this time, I was no longer a camera assistant and had become an art director, so I didn’t go to the shoots very often. I was making things like the sets, characters, and kaiju for the movie. I remember, for Mighty Jack, the work environment was good. A lot of problems happen in shoots, but, because I was making the artwork, I had control over what I was doing. So it was easy to work.

BH: What are your memories of working on Mighty Jack?

YS: I didn’t have much experience making artwork for TV [series] like Mighty Jack. There were a lot of tokusatsu scenes, so we made a lot of mistakes. Each time a problem arose, we all worked together to find a solution. We got yelled at by the director, but the director himself also got yelled at, like, “We can’t use these images!”

We all got yelled at by Mr. Tsuburaya. Because we were venturing into new territory, there were a lot of mistakes to be made. But we came up with creative solutions, so it was a mixture of many good and bad things. I have many good memories about this [series].

BH: Next, let’s talk about Ultraman Ace (1972-73). Please describe designing the character of Ultraman Ace.

YS: By Ultraman Ace, I was no longer at the shoots and worked only on the design aspect. I went to the shoots from time to time but not often. I designed and made Ultraman so that the actor could move around in the suit. That was my job. There were the actors and the people who made the suits, and there were people checking the image and sound to make sure there weren’t strange sounds or things like that. If a problem arose, there were people who came up with solutions. We came across some difficulties, but I really enjoyed working on the designs.

BH: What was your inspiration or idea for Ultraman Ace?

YS: I read the script, which had about three lines about Ultraman Ace’s appearance. Coming up with the design was one thing, but I had to make sure the actor could jump and move around and fight with it on. I had to think about the material and durability to make sure the suit could withstand the action scenes because it couldn’t fall apart during shooting. But I learned all that through experience. I was a veteran by this time. I also learned how to make suits from other people.

Designing the suit itself wasn’t that hard. Mishaps arose in the process of making the suit, as well as with the material and the movements that it needed to make – things like that. But designing the suit itself was a lot of fun.

BH: It was easy, right? (laughs)

YS: Well, I guess you could say it was easy. But the difficulty came after that.

BH: How about designing the TAC mark for Ultraman Ace?

YS: The actors had to look good in the uniforms, and they had to be able to fly in space and fight in them. The uniforms were made for combat, so they had to be mobile. And they had to be beautiful and have flashy colors that kids liked, like red and blue. So I put a lot of effort into the design. I wanted the kids to think that the design was beautiful. The uniforms also had to be easy for the actors to fight in, and the actors had to look strong.

BH: You designed many kaiju for Ultraman Ace. What are your main memories of designing the kaiju?

YS: I don’t know how many kaiju I designed. I would go to the library and look at pictorial books of plants, fish, animals, and airplanes. I would study them and come up with an image that matched the script. I would draw several quick sketches, then go home and come up with three designs. I would show them to the director, wondering which one he would choose.

For movies, we knew who the director was going to be. But, for TV [series], we didn’t know who the director was until after much of the preparation had already been made. To come up with a design, I usually met up with the director to ask about his image of the kaiju and then work on a design. But, if we didn’t know who the director was going to be, I had to come up with the design on my own.

But the people who were going to make the kaiju wanted the design early on because they needed time to make it. And they were usually my seniors. They would say, “Yoshio, hurry up and give us the design!” (laughs) They got mad at me for not having the design.

BH: That must have been difficult.

YS: Yes, it was very difficult.

BH: What are your memories of Horror Theater Unbalance (1973)?

YS: In a lot of ways, Unbalance was completely different from the work I had done until then. It was a horror [series], which was a new experience for me. There were no kaiju in this [series], so that was a relief. (laughs) But there were a lot of contrivances for this [series], like the set’s breaking apart and the basement’s getting flooded or getting set on fire.

But, because we had experience in tokusatsu, these scenes weren’t too difficult to do. We knew what had to be done to get the results we wanted and the steps we needed to take. We knew what we could do and couldn’t do, so it wasn’t too difficult.

BH: I understand that you did not work on the Ultraman Taro design. Why didn’t you work on this design?

YS: I think I was busy at the time. I might have been working on another movie, or I went on vacation, or something like that. I think my assistant did the design for Ultraman Taro.

BH: Please talk about designing the ZAT mark and uniform for Ultraman Taro.

YS: I wanted to make the uniforms flashy and easy to identify. So I used colors like red and blue – colors that you wouldn’t normally wear. That was the intention behind the designs. The main audience was kids, not adults, so I wanted the uniforms to be fun and beautiful with flashy colors.

BH: Please talk about designing the character of Ultraman Leo.

YS: I don’t remember Ultraman Leo. [sees a photo] Oh, this! For the protrusions on his head, I think I was inspired by Greek war helmets.

I think everyone liked this [Ultraman Leo] design because of the protrusions. Usually, the head is like this.

BH: Ultra Seven.

YS: Yes, it’s round without any decorations. I think that’s why the design for Ultraman Leo was popular. Everyone seemed to think it was interesting because of the protrusions.

When you make so many designs, you have to come up with something different. So I would make something stick out or pull it in. But the result had to be cool; otherwise, kids wouldn’t like it. I came up with a few designs and discussed them with the director and the assistant directors to decide which one to use.

BH: In addition, could you talk about designing the MAC mark and uniform?

YS: I forget what the MAC mark looks like. [sees a photo] Oh, this. I usually made designs like this.

BH: Like the Ultra Seven uniform.

YS: Yes. A lot of uniforms looked like this. So I added this to the uniform. Usually, the uniform just looks like this, but I added a shiny silver jack[et] on top. That made it different from the other uniforms. Everyone said it looked cool.

BH: It’s more colorful.

YS: Yes, more colorful, with red and silver, so it was flashier. [referring to a photo] I added this, as well, with two knives hanging from it. It looks strong, right?

BH: Yes, it looks very cool.

YS: Yes, with a pointy helmet.

BH: It seems that you did not design kaiju for Ultraman Leo. Why is that the case?

YS: I think I was busy, so my assistant came up with the design. I had a lot of work back then and was working on many projects.

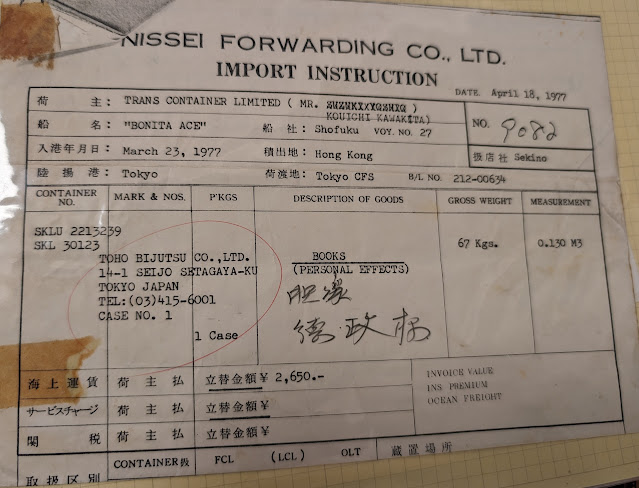

BH: Could you describe your work on Mighty Peking Man (1977)?

YS: I can’t remember what it was about. I worked on so many movies! Do you have a picture?

BH: Mr. Murase did the plastic arts, didn’t he?

YS: Yes.

BH: [shows a photo] This is the head.

YS: I think Mr. Murase did this, not me. I did the set, and Mr. Murase designed the kaiju.

I graduated from Tama Art University with the older brother [Tsugio Murase], and we worked on kaiju movies together at Toho. When his younger brother [Keizo Murase] came out from Hokkaido, the older brother brought him to me and said, “My younger brother is here from Hokkaido. Can you give him a job?”

So the younger brother got involved with making kaiju and worked hard at it. The older brother and I left kaiju work and started working on other things. The younger brother started doing a lot of things with kaiju and became independent.

BH: So do you remember this movie, Mighty Peking Man?

YS: I do. The younger Murase brother was the producer, I think. He asked me to work on the movie, and I went to Hong Kong for the shoot.

BH: Do you have any other Peking Man memories you could share?

YS: It was such a long time ago. (laughs)

Mitsuyo Suzuki: Hong Kong was with the Shaw Brothers, wasn’t it?

YS: Yes, that’s right. What was the name of the director? He was a nice guy, very interesting. The producer invited me to go out drinking, so we went out quite often. He was very knowledgeable about movies and other things. I remember talking with him about all sorts of things over drinks. (laughs) Of course, work was fun, but talking to him was much more fun. (laughs) He was a young producer, and he was very slim and tall. I wonder what he’s doing now.

BH: How did you get hired to work on Pulgasari?

YS: Pulgasari – that was the North Korean movie. I was also the cameraman for Pulgasari. We were in North Korea for a long time. They took our passports and wouldn’t give them back to us. If we said, “We want to go back to Japan,” they would say, “We can’t give you back your passports until the movie is finished.” (laughs)

Mr. Shin [Sang-ok] was the director, wasn’t he?

BH: Yes, it was Mr. Shin.

YS: I got a call from Mr. Shin. He said, “I’m going to make a kaiju movie, and I want you to design the kaiju.” Mr. Shin spoke both English and Japanese. He sent me the script, which had been translated into Japanese from Korean. So I drew the design for the kaiju and sent it to him. We went back and forth like that a few times and came up with the final design.

BH: What was the inspiration or the idea [behind the design]?

YS: The same as always. (laughs) When I read the script, I start thinking about the design. Then I make some drawings. Sometimes I’m satisfied; sometimes I’m not. I ask people for their feedback and make corrections, then come up with the final design. It takes about three days to finalize the design. I sent the design to Mr. Shin, and he was pretty much OK with it.

BH: Did he make any changes?

YS: No, he didn’t tell me to come up with another design.

BH: What was it like to work with Nobuyuki Yasumaru on the kaiju suits? Did you communicate with him?

YS: Yes. He was a sculptor at Musashino Art University. I graduated from Tama Art University. He made kaiju suits for many years. He didn’t ask me anything and just made the suits.

BH: [What do you remember about going] to North Korea for the shoot?

YS: Around this time, there were many abductions by North Korea, so everyone was worried. They told me, “Don’t go to North Korea; it’s dangerous.” My family said, “Are you sure you want to go? It’s dangerous.” But the Toho executives had already taken a lot of money. (laughs)

They took the money stacked on the table and put it in their pockets. (laughs) So we had to go. There was no choice. In the first two weeks, we met the local crew and went to the shooting locations and the studio. We came back to prepare everything, like materials and the design.

We sent everything by boat to North Korea. I came up with the design, and Mr. Yasumaru made the suits at Toho. All in all, I think it took us two months to prepare everything. Then we went to North Korea and made the set there and then started shooting.

I think it took us about eight months. It took a long time because the local crew weren’t used to the work. They had experience making normal movies, but they had never made a tokusatsu movie. It didn’t take a full year, but I think it took 10 months or so in total.

Mitsyo Suzuki: I remember that they were running out of time, so some soldiers came to help.

YS: That’s right. There were crew members from Japan, like the cameraman and the lighting and recording technicians. But we were there for so long that they wanted to go back to Japan. And the local crew started getting used to the work, so the Japanese crew was allowed to go back to Japan. So we finished the movie with the local cameraman and the lighting and recording technicians.

BH: Are there any other Pulgasari memories you could share?

YS: I have a lot of memories about North Korea. The local crew had never made a kaiju movie, so they weren’t used to the work and didn’t know what to do. They didn’t even have a studio. They had studios to make normal movies, but not for a tokusatsu movie about kaiju, so they decided to build a studio. I came up with the design for the studio, and the engineering brigade built the studio.

A tokusatsu studio has to have a high ceiling, much higher than a normal studio. And it needs to be quite wide, so it’s a big building. It was a lot of work to build it. A normal studio has to be soundproof, which is a lot of trouble to build. But a tokusatsu studio doesn’t have to be soundproof; it just needed to be really big. I handed the design to the captain of the engineering brigade, but it was really sloppy. (laughs) But they built it in no time. It took less than two months.

Mitsuyo Suzuki: You sent over a lot of things from Japan. What did you send?

The kaiju and special material, like for the camera. There were many things we couldn’t get there, so we sent a lot of things from Japan. We sent everything in a wooden box that was about half the size of this room. We also sent plastic materials to make and repair the kaiju.

BH: Did you meet Kim Il Sung?

YS: He was still very young then.

Mitsuyo Suzuki: He’s talking about the father. The current one was still young back then.

YS: Yes, he was still very young. He came to watch the shoot. I didn’t meet any of the bigwigs. But the current one came to the shoot, and he was very young.

BH: How did you get selected to work on Godzilla vs. Destoroyah (1995)?

YS: I wasn’t really singled out. The Toho producer came to me and said, “Mr. Suzuki, I want you to work on this movie.”

BH: Mr. Tanaka?

YS: No, he was more junior than Mr. Tanaka.

BH: Mr. [Shogo] Tomiyama?

YS: Yes, Mr. Tomiyama. Mr. Tanaka is much more senior. He became the president [of Toho]. Mr. Tomiyama was much younger, very slim. He didn’t have a belly. Maybe he has a belly now. (laughs)

BH: Please tell us about working in the art department on Destoroyah.

YS: What was Destoroyah about? I forget. [looks at photos]

BH: What was your working relationship with director Takao Okawara like?

YS: Yes, we worked together on this movie. He was much younger than we were. He was a very kind, humble person. Most directors are arrogant, but Mr. Okawara was a nice man. We only worked on this one movie together. But, by this time, the movie industry was waning, so I don’t think he worked in the industry for very long. I think it was hard for him afterward.

BH: Do you have any memories of the cast from Destoroyah, such as Momoko Kochi?

YS: We never worked directly with Momoko Kochi. I think she looked at the images we made and said the lines in the script, acting surprised and scared – that sort of thing.

BH: Are there any other Destoroyah memories you could share?

YS: I don’t remember much.

BH: Do you have any final comments for this interview?

YS: This kind of interview is very important. I’ve done a few interviews like this, but not many. This is also the first time I’m speaking to someone from the U.S. Well, you speak fluent Japanese, so it’s not that different from speaking to a Japanese person.

But it’s touching that you’re interested in the work we did. I’m grateful that you wanted to hear about our work. I want to help you as much as possible. We’re all getting old, so there’s a lot of things we’ve forgotten. But tokusatsu movies are very unique. We made a lot of mistakes, and there were a lot of mishaps, so it was difficult, but it was fun and meaningful to overcome those challenges.

I met Mr. Tsuburaya when I was 19 and made movies until I was 62. I had a lot of fun making movies.

Special thanks to Tabata Kei.