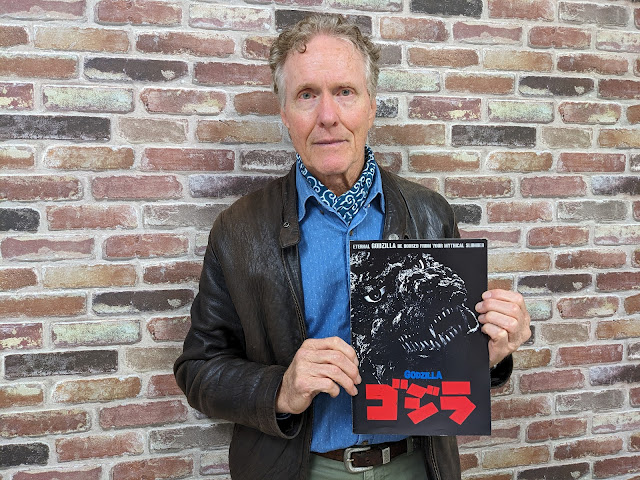

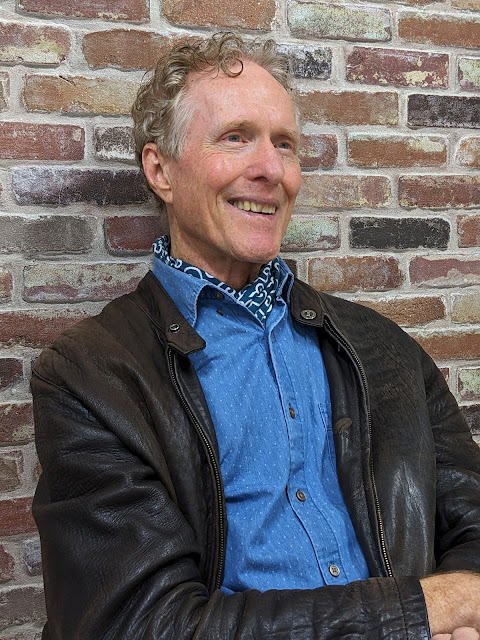

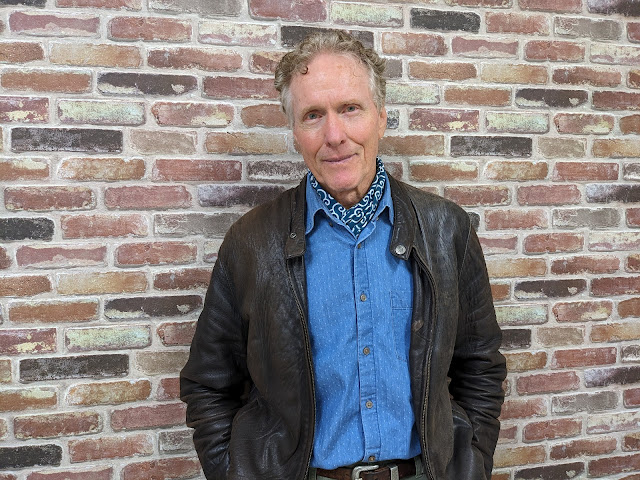

Aussie Nigel Reid never dreamed that he would end up in Japan as an actor, performing in a Godzilla movie in front of worldwide audiences, but that’s exactly how things worked out. Mr. Reid played the lieutenant commander of the doomed Russian nuclear submarine in Godzilla 1985 (1984), alongside American Dennis Falt, who played his superior officer. Not only that, but Mr. Reid can also be seen in director Koji Hashimoto’s other 1984 tokusatsu epic, Sayonara Jupiter. In November 2023, Nigel Reid visited Tokyo from his home in Australia and spoke about his acting experiences, as well as many other memories from his life in Japan, with Brett Homenick in the following interview.

Brett Homenick: First question is: Tell me about where you were born and where you grew up.

Nigel Reid: I was born in Sydney, Australia, in 1951. (laughs) It was a long, long time ago. I grew up in Sydney, but my formative years were a little different from most other Australian kids because my father ran an import business, and he invited a lot of overseas businessmen back to our house. I would sit at the dinner table in the evening with the family and listen to people from other parts of the world, and that gave me the travel bug.

In the early days, my father mainly worked with Swedish businesses, and so most of the businessmen that would visit us were Swedish. Sweden was famous for the quality of its steel, and my father was importing hardware from Sweden. But then, in the mid-‘60s, he started to import hardware from Japan. Japan was making its rise at that time.

So we started to have Japanese businessmen coming and visiting us. In fact, my father and mother helped to settle a Japanese family in the area. At that time, there was the “White Australia” policy. (laughs) It’s unbelievable the way my country has changed since then – fortunately for the better.

However, at the time, despite not being “white,” Japanese businesspeople were given a dispensation and could stay in Australia for four years. There was a Japanese family that we helped to settle in a neighboring suburb, and with whom we had a close relationship for the four years.

So early on I started to have a connection with Japan. The Australia I grew up in was a faraway kind of place – it was a little, self-contained piece of England in Southeast Asia. (laughs) However, my view of the world had been broadened when I was young, and so by the time I’d finished university I was really itching to get out of the place and see the world.

BH: Yeah, I could understand that!

NR: (laughs) My first port of call was actually a job arranged by my father, who had expanded his business operation to include the exporting of liquefied gas to the South Pacific. So my first posting was to Tahiti in French Polynesia. After flunking French in high school because I saw no purpose at all in learning a foreign language, I found myself in Tahiti with a very strong incentive to learn French so I could chat up the local girls. (laughs)

So Tahiti was my first overseas experience. I came back from my seven months there and then went to Southeast Asia where I lived in Thailand and Laos for about 15 months.

BH: Around what year was this?

NR: Tahiti was ’73. Seventy-four and -five were Southeast Asia, mostly in Thailand and Laos. I came back to Australia and worked to save some money to go off traveling again, and the next time I knew I was aiming for Japan. But it took me about seven months to travel through Southeast Asia, eventually reaching Japan.

I knew there was the possibility of finding work – either teaching English or acting and modeling – even though I had no experience. I knew that there were those opportunities, and opportunity knocked on the second day after I arrived in Japan. I was staying in a place called Okubo House, which was where most of the budget foreign travelers ended up. Bunk-bed rooms, nine hundred yen a night.

A guy from a talent agency named Tony came in looking for some guy whom he’d lined up for a job. I said to Tony, “You’ve got an agency, have you?” He said, “Yeah,” and he handed me his meishi, his business card, and said, “Come around sometime.” His office was very close by, so I went over there later that day. I walked in, and he jumped to his feet, and said, “Can you sing? We need you on TV tonight!”

BH: Oh, wow. Interesting!

NR: (laughs) It was to be in a drama about an international song contest, and they needed somebody to play the part of one of the international contestants in that contest. I didn’t speak any Japanese. I remember the one line that I had was, “Dozo yoroshiku onegaishimasu.” I wrote it down. It seemed so long and complicated, and I wondered, “How the hell am I going to remember that?!” (laughs) Anyway, that was my first experience, and then it took off from there.

I’d been traveling through Southeast Asia, staying in el cheapo dives for a few dollars a night. So, when I was paid 5,000 yen to have my photo taken for a poster, I thought, “Wow, this is great!” However, I found out I should have been getting 10 times as much. That’s when I had “certain dealings” with that agency and then moved on to another agency and started to get better money.

BH: Let’s backtrack to the beginning, going back to Australia. When you were young, what kind of hobbies and interests did you have?

NR: When I was really young, like in primary school, it was sport. In Australia, it was rugby in wintertime and cricket in summertime, and I was also good at track and field. Then, when I got into high school, I became very interested in science. I thought my trajectory was going to be working as a research scientist, which is a long way from acting in Japan. (laughs)

I did very well in high school – I was near the top of the state in science in the final exams. Got to university and became totally distracted, on top of which I had itchy feet. So I just finished a straight bachelor’s degree, didn’t bother to go on for a Ph.D. or anything like that, and just took off.

BH: What university was that?

NR: Sydney University.

BH: I see. So your bachelor’s degree was in…

NR: Science, majoring in physiology. Now the interesting connection with that was that, on my way to Japan, I’d stopped in Thailand and got really quite sick and was treated by a Chinese doctor with acupuncture and herbs. He was doing things that I could not explain with the physiology that I had studied – physiology being one of the scientific disciplines on which Western medicine is based.

So this was my first experience with Oriental medicine, and it blew me away. It really did. And then, when I arrived in Japan, by chance I had contact with a few practitioners who again were doing things that I couldn’t explain with my physiology. So I became very interested in Oriental medicine.

In a way, the things that helped keep me in Japan and attached to this country – learning the language and studying healing and martial arts – can really be traced back to my university days doing physiology and my interest in science.

(laughs) If you want one little anecdote, during the first biochemistry lecture at Sydney University, the lecturer said to us, “There is nothing special about life. It is just chemicals.” And, as a 20-year-old, I was very disappointed to hear that. I was like, “What about love and truth and beauty?” (laughs)

BH: You have to go to philosophy to hear that.

NR: Yeah, that’s right! (laughs) He’s telling me life is just a bunch of chemicals, and I was very disappointed. So I got a bit turned off science, and as I said I didn’t go on to do research or higher studies. But, when I came into contact with amazing Oriental medical practitioners, that first one in Bangkok and then those I met here in Japan, it reignited my interest in studying this incredibly complex thing called life: How do you understand it? How does disease develop? Et cetera.

I eventually realized that the biochemistry professor was correct, but he used the word “just,” and “just” has got a pejorative connotation. I realized, if you dissect reality, you will eventually get down to the chemical level, and at that level all you will see is chemicals. If you go deeper, all you’ll see is molecules and atoms. If you go even deeper, you’ll see sub-atomic particles, then quarks.

So it’s just a matter of which level you open the window to look at reality. When you’re looking at those chemicals down at the chemical level, you can ascertain a lot of interesting things, but there are emergent properties that will only emerge at higher levels, and these you won’t see. So biochemistry really is just a bunch of chemicals, but it won’t tell you about love and beauty and truth; to see those sort of things you’ve got to look at a higher level.

So what Oriental medicine was doing for me was allowing me to step back to get an overview. I could start to see the forest for the trees.

In fact, when I left Japan and went back to Australia, my plan was to go back to university because I started to see that a lot of what I’d learned in the Oriental medical field could be explained by Western sciences – as long as you knew how to look. So I thought I’d go back to my physiology and try to start to uncover some of the mechanisms that would explain how modalities like acupuncture and Chinese herbal medicine work.

However, I was very disappointed. Basically, the professor said, “OK, to go from a bachelor’s degree towards a Ph.D., you must narrow your field. You specialize and specialize.” In fact, what I needed was to step back further and further. So I gave up on that plan and never did continue. But I was also interested in sustainability and the environment and such things, and that’s where I’ve ended up back in Australia.

BH: Let’s go back to the beginnings of Japan, so let’s get the timeline on when you actually moved there, and if there’s more details about why you decided for Japan. But at least let’s get to the timeline of moving to Japan.

NR: I’d come back from Southeast Asia in 1975. I did a year of teaching high school science in 1976. That gave me enough money to set off traveling on a shoestring. So, in January ’77, I set off from Australia with a backpack, and it took me about seven months. It was in August of ’77 that I finally arrived in Japan.

Winter was approaching, which was a bit of a shock after having been traveling through the tropics. But I did know that there would be the possibility of finding work here. I’d used up most of my savings over the seven months of traveling to get to Japan, but I knew I could get some work, and then my original intention was that I would work in Japan to save some money, then take the transcontinental railway to Europe.

But I found that I really liked Japan, and I felt at home here. I could make the money here, and then go and do a bit of traveling, but I’d always come back. So Japan became my base, and it became more than just a place to make some money and move on traveling. It became a place where I wanted to learn the language and Oriental medicine and many other things.

Acting and modeling were the best way to fund that because they give the maximum amount of money for the minimum amount of work – and the minimum amount of talent. (laughs) But the acting turned out to be a lot of fun, as well. I really got into it. Not many people get paid for having fun.

And there’s a lot of downtime on a set. I could use that time to study Japanese, write letters, and read books. It was wonderful. The actual amount of time where you had to be listening to what the director wanted and performing your part as the camera rolled was relatively small. It was a long day at the studio, but a lot of that time I could make valuable use of.

BH: Do you remember your first acting job?

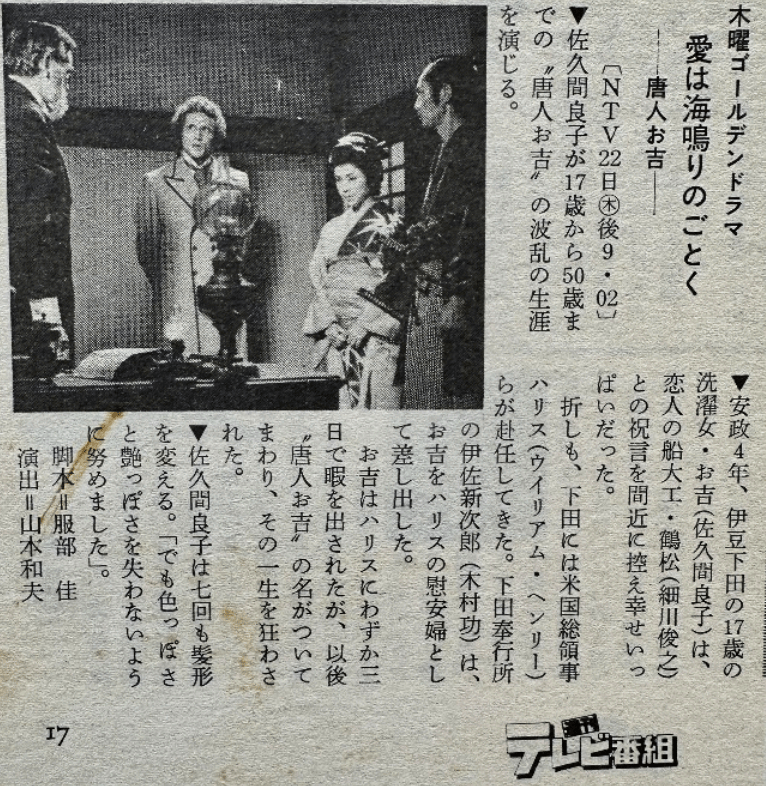

NR: Tojin Okichi (1980) was the first acting job that I had. I had had a couple of modeling jobs, but this was the first acting one. It was a historical drama. I was playing the part of Henry Heusken. I recently learned that he’s buried in the graveyard of a temple in Minato Ward, Tokyo. I might go and visit his grave sometime, given I played his part!

This was my first experience of acting. The whole cast gets together before you actually go to the location. You’re sitting in a big room, and everybody has the script in front of them. It’s just a reading of the script, but my lines happened to be the very first lines of the whole thing. So I’m sitting in this room – this is my first time – and there are all the actors there, and the director and crew.

The director said, “Go!” And the script says I have to start crying. (laughs) Of course, I balk. There’s absolute silence, and everybody looks at me! It was the first scene of the drama where I’d be riding a horse along Shimoda beach and expressing my loneliness as a foreigner in a foreign country. Anyway, somehow I got through the reading.

Then we went to Shimoda for the actual shooting. The actress who played the part of Okichi was Yoshiko Sakuma, and I was really impressed with her acting ability. At the time, she was a middle-aged woman, but in this drama she had to go from being a lively sixteen-year-old girl to a pitiful old woman, and she pulled it off so well. I was really impressed.

Also, in the rape scene, she could really struggle. (laughs) I mean, it wasn’t sexually graphic, but I had to manhandle her.

BH: How was something like that planned? In terms of rehearsing it or staging it, do you remember how? Obviously, that’s not a very comfortable thing to do. Do you remember any staging of that or rehearsing?

NR: I don’t remember that much. I remember they put me in some very daggy pajamas. “Daggy” is an Australian word; it means very drab and unfashionable. So I do remember that. It was more the violence of the scene, but I’ve been in other things where you actually have to embrace and kiss an actress. I find that really difficult because it’s one thing to be with somebody who wants to be with you, but, when you’re with somebody who is just being paid to be there and kissed by you, that makes me feel very uncomfortable.

This one was also uncomfortable partly because it was my first time to play the bad guy. But you find as a foreigner that you do take a lot of bad-guy roles. This was my first acting experience, but the guy who was going to play the part of Townsend Harris, the American consul – he had a fair bit of experience. When I told him what my role was – that I rape the girl and later get killed – he said, “You’ll find a lot of roles like that. First, you’ll rape the girl, and that will please the women who are watching, and then you’ll be murdered, and that will please the men who are watching.”

BH: Do you think that’s actually true?

NR: Well, I ended up having a number of roles like that.

BH: So, if I understand the point correctly, he’s saying that the rape is actually kind of titillation for the women watching?

NR: Yes, that’s right. That’s what he said. He had quite a bit of experience, while this was my first acting job.

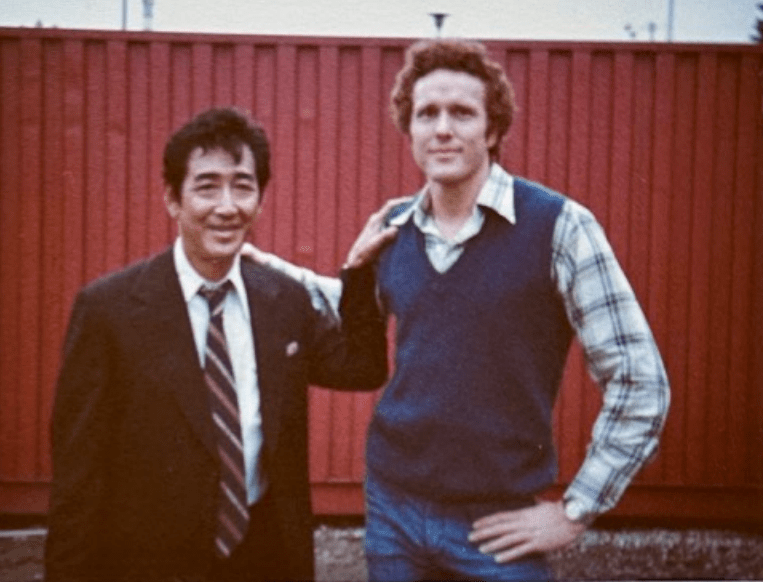

He ended up being replaced; there was some conflict of schedule or something, and another guy, Joe, an Australian, was brought in to play that part, and he’s the guy that appears in those photographs I have.

He had no acting experience, but he was an interesting guy. He had been an Olympic athlete. He swam in the 1956 Olympics for Australia, ended up in Japan, and married to a Japanese woman. He had no acting experience, nor did I, but at least I could get into the part. In modeling, you have to pose and look fashionable, and I felt very uncomfortable with that, whereas, with acting, you could move. And it wasn’t really you – it wasn’t Nigel Reid there; it was this other character. So, while I found that particular scene a little uncomfortable, Joe was just frozen stiff like this.

I went to visit him after the show had gone to air, and his Japanese wife said [in English], “Oh, Joe’s a radish actor!” I said, “What do you mean, ‘a radish actor’?” This is when I learned the Japanese expression daikon yakusha. You know what a daikon is, right? It’s a kind of radish, but it’s straight and stiff. So I learned the word daikon yakusha – a radish actor.

That was my first experience here in Japan, my first experience of what kind of a role I might be cast in quite often, impressed with the actress herself, and then learning what a radish actor is. (laughs)

BH: What about the next [acting] job?

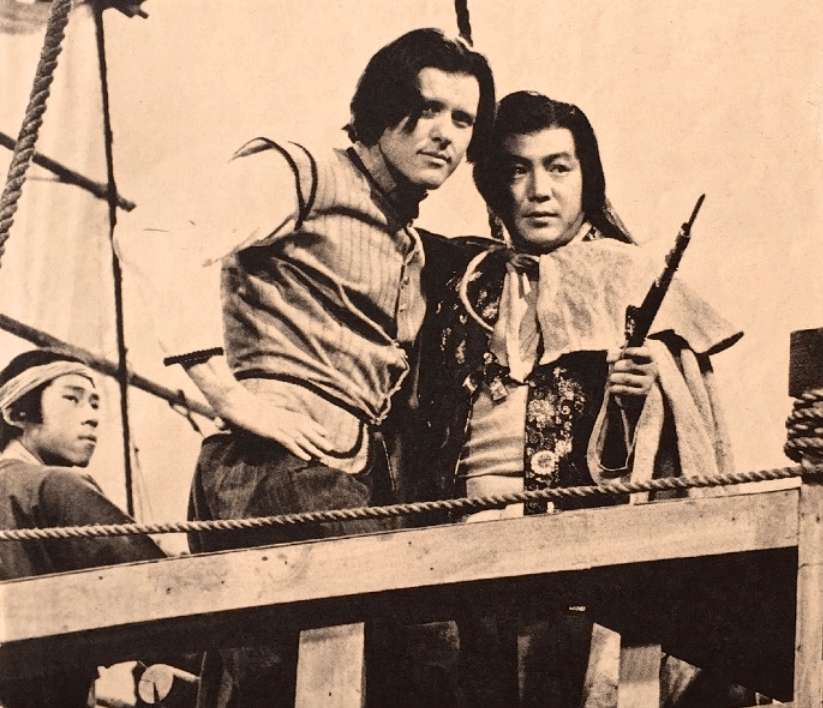

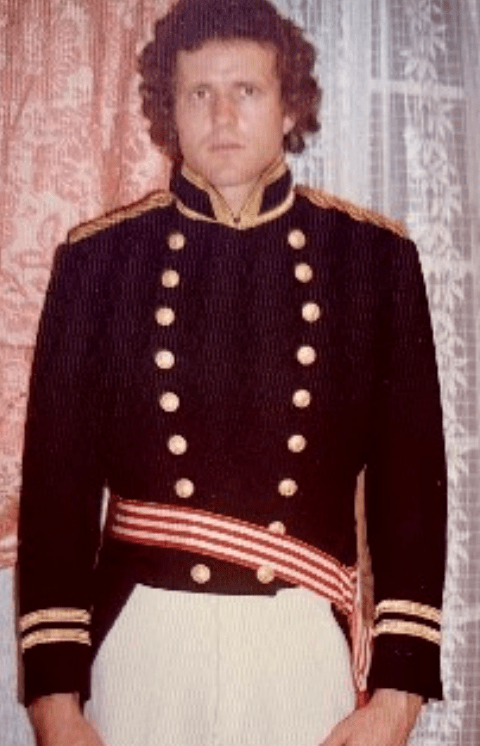

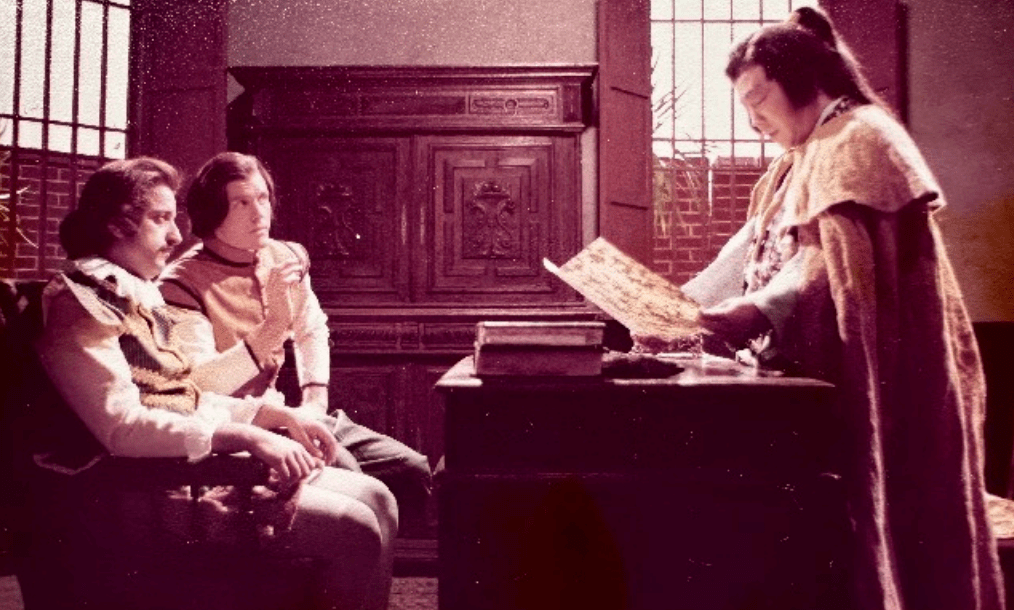

NR: Ogon no Hibi (1978) was an early one, too. That was fun. I found the period dramas were fabulous because you get to live out your boyhood fantasies of swashbuckling adventure, sword fights, flintlock guns, and dressing up in period costumes.

For example, I did The Unfettered Shogun (1978-2002), which was shot at the Toei Eigamura down in Kyoto. I could look away from the camera and the sound boom and the crew, look down the street, and I’d be transported to 17th-century Edo. There were no electric wires – there was nothing modern; they had completely recreated it all there at the Toei studios. Every person in the street would be in traditional clothes. It was, as I said, like this fantasy, like I’d traveled in a time machine, and I get to be this adventurer who comes to Japan in the 17th century and have all these adventures.

So Ogon no Hibi – that was an NHK taiga drama. I was always told by the agency, “NHK pays very poorly, but it’s very prestigious, so bite your tongue and do it.” I was playing a historical character, a Portuguese guy who was interpreting between the Spanish and the Japanese. I ended up getting killed by Ishikawa Goemon, who was a sort of a Robin Hood character of that period.

I got to ride in a palanquin and then get tipped out and die in a sword fight. That was fun.

BH: Do you have any other memories of the shooting of that?

NR: Oh, yes, I do remember this. That photo I put in my CV that shows me up on the deck of a ship next to a Japanese guy. Apparently, he was quite a famous kabuki actor. In the photo, he has a flintlock pistol in his hand. I had to shoot that pistol, and this wasn’t a fake; it was real and loaded with gunpowder.

Flintlock firearms have a little pan of gunpowder that ignites. When you aim, how close is that flash pan to your eye? I remember being really worried. It’s a lot of fun to play around with a weapon like that, but I was really worried that I was going to lose my eye if something went wrong. Those sorts of accidents used to happen quite often in the old days when those primitive weapons misfired. So that’s one thing I do vividly remember.

BH: But, when you fired it, there was obviously no problem.

NR: No, no. I’ve still got two eyes! I do remember one of my scenes – I didn’t have to actually speak in Spanish, my job was to listen to what the Japanese emissary was saying and translate it. Since my voice would not be heard, I remember deciding that I would lean towards the Spanish consul, partially cover my mouth with my hand, and appear to be whispering in his ear. That’s about all I remember. It was a very small part, but, as I said, it was fun to be in a historical drama.

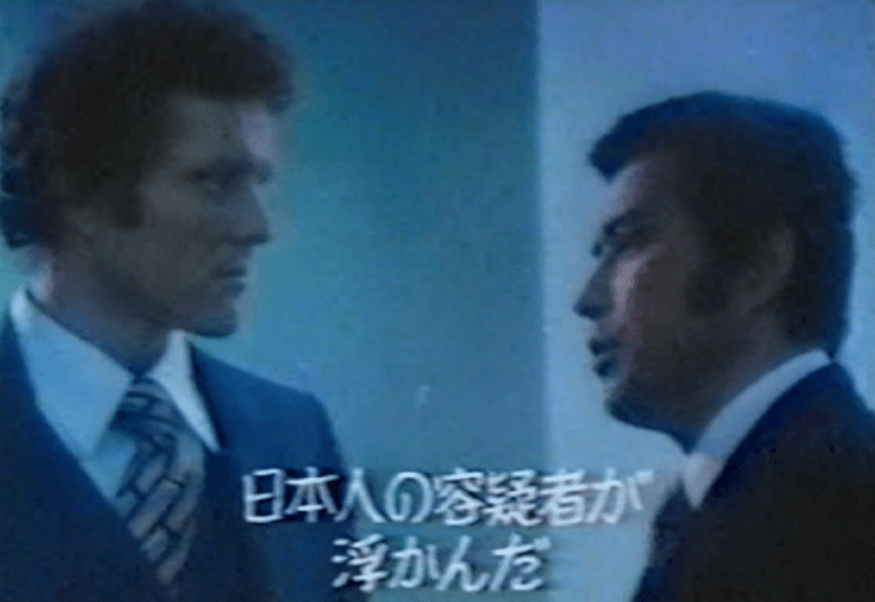

BH: Of course! Around this time, you were also in G-Men ’75 (1975-82).

NR: The lead actor in G-Men, Tetsuro Tamba was an interesting character. He had been in the James Bond movie You Only Live Twice (1967). My scene was in the Paris bureau of Interpol. My part was to speak French, which wasn’t too difficult, because I’d lived in Tahiti in French Polynesia.

Tetsuro Tamba had played the part of Tiger Tanaka in the James Bond movie, and spoke English quite well. He sat down with me and talked about what it was like working with Sean Connery.

BH: Do you remember anything he said about that, any interesting anecdotes?

NR: I don’t remember that much, but he was sort of big-noting himself. “Me and Sean were mates,” kind of a thing. But one amusing thing was, he also had some lines in French. He was so confident that he just casually looked at the lines and hardly practiced at all. He comes into the room, shakes my hand, and delivers these lines, which are almost unintelligible – his pronunciation’s so bad. But he’s got that confidence to pull it off.

And then Go Wakabayashi was really nervous about it, and he was really studying the lines he had to deliver in French. When he’s just about to walk out and deliver his lines, Tetsuro Tamba is standing there and says [in Japanese], “I wonder if you’ll be able to do it.” And that really made the poor guy even more nervous, trying to deliver his lines in French. (laughs)

French is a very difficult language for a Japanese speaker. Spanish is one thing, but the pronunciation of French is very difficult for a Japanese person.

Anyway, I’d been a bad guy a number of times, but in this particular episode I eventually got to be one of the good guys.

BH: Was G-Men ’75 also the show where you had the picture holding the gun?

NR: Yeah.

BH: Why don’t you tell that story.

NR: This was before the days of everybody having a smartphone with a camera, so I don’t have that many shots of myself in costume and on the set. During the shooting of one G-Men episode, I had a big .44 Magnum, and I was dressed as a detective. I was fooling around with the young actress Iyo Matsumoto, pointing the gun at her. Somebody happened to take the photos of us, so I put it into my portfolio.

Many years later, I’m back in Australia, and have a son. My wife and I got married in Japan in 1988 and moved back to Australia at the end of 1990. My son was very impressed with those photos of me with the .44 Magnum, and he told all his friends at school, “My daddy has a big gun!” (laughs) I guess he thought it would give him some cred in the schoolyard.

It’s difficult for a child to understand the difference between reality and what’s on TV. Everything seems to be real. So a photo of me with a gun, that’s really my daddy, and that’s what he used to do – he used to wield a gun.

In one of the other jobs I had, I was an American G.I. traveling around Japan to primary schools, promoting the school lunch program. The Americans were enlightened occupiers: the Japanese population was starving, and they initiated the school lunch program. I had quite a big speaking part in that, and I had an interpreter with me. I was a G.I. speaking my lines in English, and then the interpreter translated it into Japanese. I’ve got that on video – I’ve got quite a bit of my acting work on video.

My son was watching this, and he turned to me and said, “Why didn’t you just speak to them in Japanese?! You can speak Japanese!” Again, he didn’t realize that I was playing a role – an American G.I. who doesn’t speak Japanese. So it was fun to watch my son evolve in his awareness of the world. For example, he’s half Japanese and half Australian, and my father, who did a lot of business with Sweden, was actually knighted by the king of Sweden for his Australian-Sweden business work.

My son knew that his grandfather was a Swedish knight, but was puzzled as to what that made him: “Daddy, am I Swedish, or am I Japanese, or am I Australian?” He couldn’t quite figure out what he was. “How come you don’t have the big gun anymore?” (laughs)

BH: What year was G-Men ’75? Do you remember?

NR: That would have been in the early ‘80s.

The final chapter in the story of my association with G-Men ’75 involved me actually being arrested – this time in real life – by the Japanese police. It was the emperor’s birthday, and I was out and about near the Imperial Palace when I was picked up by a young police officer for not carrying my foreigner registration card. Back then, all gaijin living in Japan had to carry one.

He also nabbed a young Thai student and led us both towards the Marunouchi Police Station. When I say he led us, that’s exactly what he was doing – walking in front of us and only occasionally looking back to check that we were following him. The thought occurred to me that I could simply duck down a side alley and escape. But I decided to go along for the ride.

When we arrived at the police station, it was obvious from the reaction of the senior officers that this young officer had been overzealous, and they really had more important things to do than booking us two minor offenders. Naturally, I had to give details of what I was doing in Japan.

When they heard that I had been appearing in G-Men ’75, their interest perked up, as they were naturally very familiar with the program. We ended up having a very animated conversation, after which they gave me a lift all the way home in their patrol car.

BH: I think another role you did was the Saturday Wide [Theater] (1977-2017) with Koji Tsuruta. So what could you tell us about Mr. Tsuruta and this program?

NR: That was one of the very early programs I did. I was a cop, so was Koji Tsuruta. We were partners, and in this scene I got shot. I’d seen the kind of cinematic effect of a bullet hole appearing in somebody’s clothing when pierced by a bullet, and blood spurting out – very graphic.

But I never knew how it was done till they wired me up with a small explosive charge inside my suit. I had a heavy rubber protective vest between my skin and the explosive, and a condom full of red dye next to the explosive. They weren’t going to shoot it in two separate takes; it was just one take.

So they had to coordinate the shooting of the gun with the hole appearing, and blood spurting out. So there was a detonator wire from that explosive charge that went down inside the leg of my trousers, ran along the ground [concealed], up inside the shooter’s clothes to his gun. There was an electric charge created when he pulled the trigger, the shot was fired, and simultaneously a hole appeared in my clothes, and blood spurted out.

So at last I knew how that effect had been done in the many movies that I’d seen. A couple of things about this program that have stuck in my mind: I was very keen to make it realistic, so in the rehearsal, rather than crumpling to the ground on being shot, I acted as if I’d been blown straight back. Unfortunately, there was no protective padding under me, so I fell very heavily on the gravel and really hurt my sacrum. But I managed to soldier on, got up, and redid it for the actual take.

BH: Did you have to change clothes for that?

NR: No. There was only one actual take. The initial one was just a rehearsal without the explosion and blood. But I wanted to make it look really good, and that’s when I hurt myself.

I do remember, on the real take, Koji rushed over to me and cradled me in his arms as I was dying. I remember looking up at his face – and, again, this was an early experience of seeing a good actor up close – I’m lying there, and he’s expressing this incredible shock at his friend being shot and dying in front of him.

I’m looking up, and he’s showing such concern for me. This guy doesn’t even know me! This is just acting, you know. He’s just met me today. But it was so believable – the distraught look on his face, the anguish of his mate being killed. That is a very strong memory I have of him – great acting! (laughs)

BH: Do you remember what he was like off the set or any conversations you had?

NR: No, I don’t. I spoke pretty much no Japanese at that time. That was a very early job; there would have been an interpreter there. In terms of the Japanese actors I do remember interacting with, unlike in Western countries – America, Australia, etc. – where actors can have pretty big heads, and be pretty full of themselves, not so in Japan.

I remember in one job I had there was a very famous singer and actor named Julie; his stage name was Julie.

BH: Kenji Sawada?

NR: Yeah, and I was doing something with him. He was one of the biggest properties in Japan at that time, and I remember the way he was interacting with me – I’m a nothing, but he treated me with such respect. And also, when he was interacting with the director, I was struck by how humble and cooperative he was. I remember being extremely impressed. And that was the same for pretty much everybody, all of the Japanese actors I observed. No matter how famous they were, they didn’t try to lord it over others on the set. They knew their place. The director was the boss. I was very impressed with that.

BH: Another role that you did, probably around this time, was The Unfettered Shogun. I don’t think we’ve talked about that too much yet, so what about that one?

NR: I’ve got a couple of little anecdotes on that program. That was another one where I raped the girl and then got killed. It was shot at Toei Eigamura, which was a big open-air set in Kyoto. I went down there by myself, as by this time I spoke enough Japanese. There was a guesthouse just next to the Eigamura.

So I’m staying in the guesthouse, and the young actress who’s going to play that part of the girl I rape was staying there, too. The morning of the shoot, I came down for breakfast and sat at the table with her, and her mother was there with her. It was not just this girl that I’m going to do a rape scene with, but her mother was there, too! (laughs) And the mother was coming along to the studio, as well!

Some of the techniques that were used in Japanese moviemaking at that time were quite new to me. At the time, I thought they were overdramatic – lots of extreme closeups, and in this rape scene shooting the action with a strobe-light sort of effect to intensify the violence as I’m ripping at her kimono. I’ve seen some of those techniques in Hollywood movies subsequently, but, when I was seeing them in Japan, I was thinking, “They’re overdramatizing things a bit.”

So I think Japan might have been ahead in some of these sort of effects. It wasn’t the CGI sort of special effects that can be done digitally now. But still they created very realistic effects – like, for instance, in one of the G-Men episodes there was a closeup of a bullet going into my eye. Things like that.

Anyway, back to the Toei Eigamura set where I did the rape scene. There was no nudity, but still the girl had her mother there to watch the action! During the action, the director says to me he wants me to appear more excited. At that time, I didn’t know the Japanese word, kofun, which means “excited” or in this context “aroused.” He says it to me, and I do a double take, and the girl who’s lying down there, she turns to me and says, “Act more excited.” (laughs)

BH: In English or Japanese?

NR: In English, because at the time I didn’t know the word kofun. Her mother was right there, and the director is trying to get the message to me by going like this, using his arm to indicate an erection.

BH: (laughs) And she’s lying on the ground when she turns to you and says that.

NR: Yeah, she’s lying on the floor. Her part is to struggle and struggle and then bite her tongue off and bleed to death. It’s horrible! When I saw the actual scene itself, using the strobe-light technique of me ripping at her obi and kimono, and everything sort of stops and starts in a jerky fashion like the way movements appear when seen under a strobe light. So though there was no nudity nor anything sexually explicit it was just very violent.

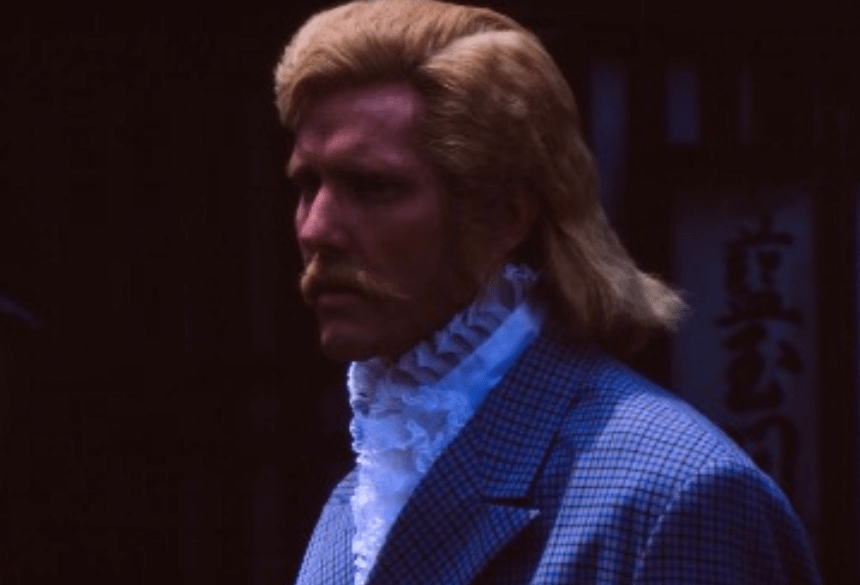

And then, in terms of the violence, later there was the scene where I actually get killed by Ken Matsudaira, who plays the part of the shogun. This was done in one of the sound stages. You know, at Toei or Toho, you have all of these sound stages, a long avenue of sound stages. And I’m standing there all dressed up in my role as a Dutch arms dealer, ready for the scene in which I’m going to be cut down by the shogun.

I was standing at the door of the sound stage, looking down the avenue of sound stages, and way off in the distance I see a figure approaching on a little moped, and it’s the shogun. He’s coming to kill me, and he’s got a popsicle in one hand. He’s in the complete outfit as the shogun, riding this little motor scooter, sucking on a popsicle. (laughs) And it’s like, “The shogun’s coming to kill me, and he’s putt-putt-putting along with a popsicle in his hand!” (laughs)

Anyway, so then the scene is going to be shot. I was short-sighted at that time. I’ve had an operation since, and now I don’t wear glasses, but then I did. Obviously, I couldn’t wear glasses when I was acting, so I always wore contact lenses.

Sometimes, when wearing contact lenses, if one of them slips out of place when your head gets bumped, it’s very difficult to try and get that contact lens back into place. So, in this scene where I get killed, Ken Matsudaira comes towards me with his katana raised, brings it down on my head, and I fall back against the shoji [paper sliding door], and slowly slip down, dying.

In the action, one of my contact lenses was partly dislodged, so, as I’m sliding down the shoji dying, my eyes are fluttering like this, trying to get that contact lens back into place as I die. After it had gone to air, I was at the shiatsu class where I was the interpreter for the foreign students, and my teacher said, “ Nigel, I saw you in The Unfettered Shogun, and your acting was so good! I just loved the way your eyes were fluttering as you were dying!” (laughs) He put it down to my good acting when, in fact, it was just that my contact lens had become dislodged by the action.

There’s another funny incident about The Unfettered Shogun program. When that episode went to air, I was at a summer camp where I had a job to teach English. That evening, there were lots of lovely female students, and one other foreign teacher, a New Zealand guy, and everybody sat down to watch Nigel-sensei on the TV. It was so embarrassing that the rape scene was going to be seen by all of these students who were studying English with me on that summer camp.

There’s one line where one of the Japanese characters describes me as having giragira me. Giragira me is like sort of – what could you say in English? – leery eyes, like a pervert. (laughs) So I started getting teased by the students and the Kiwi guy: “Giragira me!” Lecherous eyes.

BH: How about Kido (1981-82)? I think you were asking for directions in that.

NR: Yes. In that one, I’m a dorky gaijin who is lost, and I ask directions to the Australian embassy. The girl, Kido’s assistant, gives me directions in English, and then I thank her in Japanese. It’s quite a small scene.

This scene from that program later made an appearance at Yoko and my wedding. We got married at Meiji Jingu, which was a very unusual thing in those days. Most weddings were conducted in a big hotel. But somehow I found out that we could get a real wedding, a real Shinto wedding, at a real Shinto shrine, which was Meiji Jingu – probably the most important Shinto shrine in Tokyo [and] a big tourist attraction.

In fact, there was a film crew from New York who was there at that time, and they actually filmed our wedding procession. Unfortunately, I never got to see their footage. Then our wedding reception was held at Meiji Kinenkan, a special building that had been built for the Meiji emperor. It had fallen into disuse, though now it’s been restored and has become a popular venue for wedding receptions.

So, back then in 1988, we were quite ahead of our time in arranging those two venues. I really pushed for it. Yoko’s mother thought, “No, nobody does that sort of thing. It’s got to be in a big, prestigious hotel.” But I resisted, insisting, “No, I want the real Japanese thing!”

At a Japanese wedding, a lot of it has to do with photo opportunities and costume changes. So, initially, we were in traditional Japanese clothes – Yoko in a kimono, and me in hakama and haori – the full traditional Japanese formal attire for men. And then the couple goes out and gets changed into Western attire: I wore a tuxedo, and Yoko a Western-style wedding dress, and we then come back in.

During that break, in order to keep the wedding guests entertained, they customarily do a slideshow of old photos of the bride and groom when they were growing up – you know, family shots – and then perhaps a couple of shots of them in their early dating days. That’s just to entertain the wedding guests. And you know what they showed for mine? A whole collection of video clips of my acting! (laughs) I put the video together, and naturally I made sure I didn’t have any of those sorts of scenes!

As Yoko and I were out the back doing our costume change, we didn’t get to see the guests’ reaction to it, but my friend, who was my best man, said, “Oh, it was hilarious.” The Kido episode was appropriately the last clip in the video sequence I’d put together. Me asking directions to the embassy – this dorky Australian guy asking for directions to the Australian embassy.

One other anecdote about Japanese weddings. In Japanese culture, you put everybody else up on a pedestal, and you put yourself and your family down. So the parents of the bride and groom sit right at the back of the room. However, my father had come all the way from Australia to be at his son’s wedding. (laughs) He said, “What’s this? I’m going to be at the back of the room?!” So Yoko’s parents agreed to make a special exception for my father.

BH: Well, how about Proof of the Man [the 1978 TV version]?

NR: Proof of the Man, that was probably my first acting job. I was really just an extra. Everybody knows about the two atomic bombs, but not many people know that almost every major city in Japan was firebombed. In fact, there was a big argument in the American military – those behind the Manhattan Project for the A-bomb kept on complaining that the massive, ongoing bombing raids would leave no cities left for them to try out their atomic bombs.

Anyway, this was a scene in firebombed Tokyo, and I was an American G.I. sitting on the back of a jeep as we’re driving through this burned-out wasteland, throwing out Hershey bars to Japanese children dressed in rags running behind the jeep and calling out [in Japanese accents], “Chocolate, chocolate!” We were throwing Hershey bars to them. At the end of the war, pretty much the entire population was starving.

So I did this scene. I didn’t really think much about it, and then I went home that evening to the share house I was living in. There was a collection of people there, as there often is in a share house. I described to everyone the scene that I’d been in. There was a middle-aged Japanese businessman who was visiting us that evening, and he got a faraway look in his eyes.

He said, “I was one of those children who was running after the jeeps begging for chocolate.” It had just been a job for me; it didn’t have any reality to it. But then going back home and finding it was, in fact, very real – that’s what was actually happening. This guy had actually been one of those children. That really brought it home to me.

BH: Do you remember where they shot the scene of the bombed-out Tokyo? Where was that?

NR: No, I don’t. It’s 45 years ago.

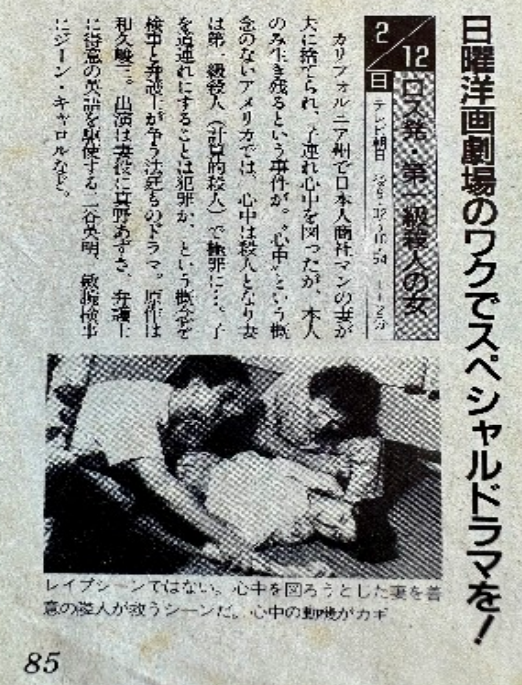

BH: And then another one, I think it’s another rape scene, [is in] Sunday [Western Movie Theater] (1966-2017). [This drama, entitled “Woman from Los Angeles Accused of First-Degree Murder,” aired on February 12, 1989.]

NR: Yeah. This scene actually caused an amusing incident with my wife’s family. I’d gone back to Australia on a visit and met Yoko there. She was on a working holiday visa in Australia. We came back to Japan and, after about a year, got engaged.

Yoko marrying a foreigner wasn’t such a big deal. However, when Yoko’s parents were married, they were both from samurai families. It was in the early postwar period when they got married, and in Japan at that time it was important that, if you were from a samurai family, you’d marry somebody from a samurai family.

By the time we were married, there had been quite a change. (laughs) And also Yoko’s father worked for an American insurance company, and he spoke very good English. So it wasn’t a big deal for Yoko to marry a non-samurai or even a foreigner.

Anyway, I did the rape scene for that program. I do remember the scene very well. It was based on the true story of a Japanese woman who was living in L.A. She tried to commit suicide, and I think she tried to kill her children, as well, because she didn’t want her children to be left behind. This is a different perspective – the Japanese way of looking at things and the Western way of looking at things. The Japanese mother would be thinking it would be cruel to leave her children behind without a mother.

My scene had me and another guy standing at her door. The door opens, the camera’s behind us, and all the camera can see is the back of our heads and her face when she opens the door and sees these two strangers. The camera captures the fright on her face.

It can be a lot of fun clowning around on a set. Before the actual take is done, you always do a number of rehearsals, and I knew that [neither] the camera [nor] the director – nobody – could see my face; the only one that would see my face is the actress when she opens the door.

She opens the door and has to act really afraid, so I pulled this ridiculous, comical face [starts mugging with his tongue hanging out the side of his mouth] to try and see whether I could put her off and make her laugh. (laughs) However, to her credit, she managed to hold it together, but I noticed she did complain to the director about what I’d done.

An article about the TV program appeared in the newspaper showing a photo of me and the other guy holding this poor woman down on the floor. Unbeknownst to me, Yoko’s auntie down in Osaka opened the paper and saw this photo and recognized me. She said, “Is this really the guy that my niece has married?” (laughs) Obviously, she’s an adult and, unlike my son, did not believe it was reality. Even so, I can imagine it would have been a shock for her.

BH: I think another role you had was in Kon Ichikawa’s The Burmese Harp (1985). You were in that film, so what do you remember about that, especially about director Ichikawa?

NR: I can’t remember my interactions with the director. I do remember that, in the part that I was playing, I tried as much as possible to look at and speak to the main character with as much disdain and ridicule as I could muster in the tone of my voice and the expression on my face.

I don’t remember much in the way of directions from the director, but he obviously wasn’t displeased with the way I did it. Later on, there was a scene where I had to speak in English to my commanding officer. In many of my previous roles where I’d played the part of an American, I had decided not to try and imitate an American accent because it would be fake, and any American watching would know it – and probably react like Australians do when we hear an American actor trying to do an Australian accent.

Although, naturally, very few Japanese people watching would be able to tell that I don’t have a proper accent. But, in this case, I decided as an Australian I think I can do a pretty good English accent. So, in the English lines I had in that movie, I did speak with an English accent. I think I probably got away with it. Obviously, when I spoke in Japanese, it comes across with an accent. But that’s fine; that was my role – that of a foreigner speaking Japanese.

I really should have been looking into what the story was about before the actual shooting. After the movie had been finished, I did read up on the history, the true story behind this Japanese soldier who had been so appalled by the horrors of war that he’d become a monk in Burma. I ended up going to Burma years later, visited many temples, observed the monks, and was enchanted by the people and the culture.

I’m sorry I can’t give you very much about that particular job, apart from the fact that I’m glad that I got the chance to be involved in a movie like that based on such an amazing story and with a strong anti-war message.

BH: Now we’ll finally get to the science fiction films that I wanted to ask about. The first one you did was Sayonara Jupiter (1984). What do you remember about filming this and getting cast and that type of thing?

NR: Not too many anecdotes about that. I do remember there was talk about some French woman being brought in as an actress, and there was some dissatisfaction about that. I don’t remember exactly, but I remember there was talk about the French actress.

Another thing I do remember, in terms of French things, was that on the set there was a French guy who was an extra. And this guy didn’t speak any English, nor Japanese. We native speakers of English are very privileged in that we can go almost anywhere in the world and expect to find somebody who speaks English.

The thought occurred to me, “Here’s this French guy. He’s going off traveling, and he doesn’t even speak English. How does he survive?!” Because I’d lived in French Polynesia, I could speak French, and I do remember interpreting for the director – conveying the director’s instructions to this guy, interpreting from Japanese into French.

Switching between your native tongue and another language is one thing, but, between two foreign languages, in this case Japanese and French, it’s more difficult. At least for me it is. I remember translating the director’s directions to the guy in French, and then turning back to the director, and I had a lot of trouble getting my Japanese happening again because my mind was still stuck in French. I know some people can switch between foreign languages quite easily. It seems to be a special skill, one that I have not mastered.

BH: Do you remember what the directions were?

NR: No, I don’t. He was just an extra, so there wouldn’t have been very much. I don’t know how he even arrived at the airport, got to accommodation, or got onto this job without speaking any English or Japanese.

BH: Speaking of the director, Koji Hashimoto, he also is the director of the Godzilla movie in which you appear. Do you remember anything about Mr. Hashimoto, the director?

NR: No. Again, I’m sorry, I don’t. There are instances where I remember my interactions with the director, but unfortunately in this case only the translating incident. I’ve read the interview you did with Rachel [Huggett]. Rachel was in the same agency as me, and I knew her quite well. So it was very interesting to read your blog and find out what happened to her.

Reading Rachel’s interview brought back the memory that there had been some issue between the guy who’d written the script [Sakyo Komatsu] and the director. There was some tension there; I was aware of it at the time but had forgotten until I read Rachel’s interview.

In terms of the scenes I did, I have a strong memory of the part where I heard a signal coming in, and I thought, do I sit there and just listen to it and report what I heard, or do I pretend to be straining to hear a garbled signal coming in through my headphones? I decided to act as if I was straining to hear, even though the director had not given me any instructions.

Another memory I have was the final scene where I leap up and shout, “Success!” and then I see everybody is really sad, and I sit down. So the challenge for me was, how do I create with my body something of my feeling? I did it by very slowly lowering myself down to my seat.

After leaving Japan, I have not done any acting work. However, I did find myself in a situation where I had to use the acting experience I’d gained in my Sayonara Jupiter role. I was called up for jury duty at a time when I was very busy. It was a murder trial, and they usually go on for a very long time, so I really needed to get out of having to do it.

I tried giving the presiding judge what I thought was a reasonable excuse – being too busy – but he didn’t buy it. The only remaining chance I had to get off the jury would be when the accused was given the right to reject a small number of those who had been selected to be on the jury. There were more than 12 of us potential members.

We had to stand up one by one, and the accused and his legal counsel would look at us and decide whether or not we might be sympathetic to his case. He was across the other side of the courtroom and would not be able to see my face clearly, so I resolved that I would have to use body language to make myself appear intimidating from across the room.

The thought occurred to me that, if I was going to succeed, this was going to have to be the best bit of acting I’d ever done. I did the reverse of what I’d done in Sayonara Jupiter where I’d sat down slowly and tentatively. This time, I stood up very slowly and deliberately, making my body appear to grow larger and larger as I rose to my full height while fixing my eyes on him in an unblinking stare.

It worked! I saw him immediately lean across to his legal counsel to say he didn’t want me on the jury. I left the courtroom with a great sense of relief – and achievement. I never bothered to follow the case in the news and find out whether or not he was eventually convicted of murder. Perhaps I really should look into it.

BH: Going back to Sayonara Jupiter, when you’re talking about the acting [choices that were made for your character in that film, were they] your choice, or did the director give you that direction?

NR: Well, unfortunately, I can’t remember. He certainly didn’t give me any directions in the scene where I was trying to listen intently. However, I would have been told by the director to leap up excited and then, when I saw that everybody else was sad, to sit back down. But I don’t think I got re-directed to sit down more slowly. I think I figured that out myself – instead of just sitting straight down, I slowly lowered myself down.

I wouldn’t want to blow my own trumpet and say that I’m good at acting because I don’t have any real training. But one of the things about being in Japan [is], when I first arrived, nobody knew me. If I had been back in Australia, I would have been far more self-conscious. And the worst thing to be if you’re an actor is self-conscious. As I’ve said, as a model, I was self-conscious because it was my face there. But, as an actor, I was being someone else.

Getting into costume and onto a set made it a lot easier. It just put you in a different world. It was no longer me, Nigel Reid, there on the set; I had become somebody else.

BH: One last question about Sayonara Jupiter: Obviously, there [were] a lot of foreigners in this movie, like, [as] you mentioned, Rachel. There was Ron Irwin and a couple of other foreigners, as well. In terms of the major people [playing larger roles], did you have any interactions with Rachel or Ron Irwin?

NR: Well, I don’t remember interacting with Ron, just with Rachel, simply because I knew her. She was from the same agency as me.

One of the jobs I ended up doing in Japan was teaching shiatsu, mainly to foreigners. People get surprised – it’s a little bit like a Japanese guy going to Australia and teaching boomerang-throwing. I think Rachel actually came and did one of my courses. I’m pretty sure she did.

BH: What agency was that?

NR: It was called Hoko. Here’s a good story for you. I’d initially been in Tony’s agency. I’ve got a lot of respect for Tony; he was an Iranian guy who’d come to Japan in the early days. He spoke really good Japanese, and he had set up a talent agency, although I’m pretty sure he was backed by the yakuza. There’s a lot of underworld involvement – same as in Hollywood. The Mob is there, and it’s the same in Japan.

So Tony got me on TV, doing that drama about a singing contest. Then I’d done that poster for him and got 5,000 yen and later found out it should have been 50,000 yen. So, on the next job that Tony got me, I thought, “I’m going to make sure I get proper pay for this.” The job was a commercial for Sharp televisions. I’ve got a couple of photos – it was meant to be a world title fight: a white fellow against an African-American guy.

Fortunately, he wasn’t a Mike Tyson. (laughs) I actually had to be a bit careful that I didn’t hurt him because I’d been a weightlifter; I was pretty strong. And I’d done some boxing.

I’m going to do this scene, and I know that the payment that I’ve been promised is very low, so I decided I was going to do a mini strike. Before the final scene could be shot, I was just going to sit down and say, “I want to get proper pay for this.” Tony’s agency had sent this guy with me as interpreter, and he was a little chimpira [a young hoodlum] kind of a guy.

My little strike action failed because I realized that I was holding up the whole production crew and everybody who had nothing to do with my payment; it was just between me and the agency. So, eventually, I completed the scene. I was really frustrated. I remember standing there, having just done this fighting scene. I didn’t have the gloves on anymore, but I was really fired up. And this little chimpi [short for chimpira] guy is standing in front of a plate-glass window, and I was going to put him through it.

I was so close to it, but I realized that this would be the end; I’d be out of Japan. So I held back and lived to fight another day.

BH: You were very close to doing it.

NR: I was very close to punching him right in the face, and he would have fallen back through that plate-glass window. I was so angry. After that, I moved on from Tony’s agency. As I said, in spite of the issue I had with him over pay, I’ve got a lot of respect for Tony because he was a foreign guy who came to Japan in the very early days and made it.

So I moved on to another agency that I’d heard about. It was a really good agency, and I was starting to get jobs and good money. It was run by a woman – I won’t mention her name because she’s probably still alive. Anyway, she had an eye for young foreign guys. I remember one of the Japanese guys working for her said, “If you want to get a lot of jobs in this agency, fuck the boss, ‘Ms. M.’”

I didn’t; I wasn’t going to get involved in that way. In spite of that, I ended up running afoul of the boss by pure bad luck. They had got a job for me where I had to go down to Osaka. My younger sister had just arrived in Japan, and she was backpacking around. We were going on the shinkansen [bullet train] together down to Osaka. I was going to go to the hotel that had been booked for me by the film crew, and my sister was going to go to a backpackers’.

It was wintertime. We got off the train at Shin-Osaka Station, and I realized I’d left my gloves on the train. I jumped back on the train, dashed to my seat, grabbed my gloves, and got back to the door just as it closed. The train pulls out, and my sister, who doesn’t speak a word of Japanese, is on the platform with our bags screaming, “Oh, no, what am I going to do?!”

When I got off at the next stop, I explained the situation to the station people – by that time, I could speak enough Japanese. They called back to Shin-Osaka Station, I spoke to my sister, and she waited there until I finally got back. Unfortunately, by that time, it was too late for her to get into the backpackers’. So we went to the hotel that I’d been booked into by the production company, and I explained to the director about this little mishap, and this is my sister, and she’ll share the room with me.

Unbeknownst to me, they didn’t buy my story; they thought I’d picked up some floozy on the train. (laughs) And, at their expense, she’d be staying with me in the hotel, which is a real no-no. So I did the job; I had no idea that anything was wrong. I rang back to the agency. Mickey, the young Japanese guy there, said, “Better get back fast. ‘Her name,’ the boss, is really pissed off with you.”

So I got myself straight back to Tokyo. I already knew that she’d been disappointed with me because I hadn’t slept with her. She’d actually taken me to some late-night jobs in her own car and talked about her personal life. It really did seem that she was after me. Then, with this screw-up, that was the end of it. I realized that she had decided that I wasn’t going to get any modeling work again in Japan. So I had to try and find a new agency.

I had even less luck with my next agency. It was set up by the son of a Japanese diplomat – I won’t give any names. It turned out to be no more than a front for trying to bring young foreign female models into Japan for the old man to “take advantage” of. I think they were hoping that I could introduce them to some models.

Before I twigged on what was going on, I did contact a Czech girl I had met when traveling in Europe. She was very attractive and had begun doing a lot of modeling around the Soviet Bloc countries. Fortunately, she was unable to come. The agency never got me any work and probably couldn’t have, anyway, as I later discovered that Ms. M from my previous agency had blacklisted me by spreading stories around the modeling industry about me being unreliable.

So I moved from there to Hoko, which was getting more of the acting rather than modeling jobs. So I managed to continue working in Japan, which was very fortunate. I ended up getting lots of good jobs through Hoko.

So my first agency had ripped me off me on the pay. The second one involved that little problem with the boss. The third one was a potential disaster. Finally, I struck it lucky with my fourth agency. Hoko was great. Kii-san, the principal there, was really good to me – got me lots of jobs. I seem to remember that it was Kii-san who informed me that Ms. M, the boss of my second agency, had been badmouthing me around the industry.

As I mentioned before, I suspect Tony from my first agency had a connection with the yakuza. Then, much later, I had another run-in with the Mob. During the Japanese real-estate bubble, I was living in a house in Takanawadai. As a tenant, you have very strong rights in Japan, as you do in New York City, but probably even stronger in Japan. So, if the landlord wants to sell the house and move you out, they have to pay you quite a bit of money to leave.

The landlord died, and his son sold the property to a jiageya. A lot of real-estate speculation was occurring in Japan at the time, so the government, in order to stop this dangerous real-estate bubble, put restrictions on bank lending. So who steps into the void?

BH: The yakuza.

NR: The yakuza. They set up what were called jiageya – front companies that were kind of real-estate companies, and they continued fueling the bubble. The house I was living in had been sold to one of these companies. So they were trying to evict me.

There were a lot of areas where a jiageya had bought up all of the land, apart from one remaining house, where the owners, often an elderly couple, didn’t want to sell up and leave, and so they’d be intimidated. So the idea was to intimidate me.

The landlady herself had tried to kill me.

BH: What?

NR: She was 86 years old; she couldn’t kill me. Me holding out was an emotional issue for her – unlike the yakuza who are businessmen.

BH: Well, wait – you can’t just leave that anecdote. How did she try to kill you?

NR: (laughs) I was very lucky as a foreigner to know about the tenants’ rights in Japan. I was living in a beautiful old house in central Tokyo – cherry blossom trees, garden, the whole traditional Japanese house and garden deal. It was a house that had always been rented out to Fulbright scholars. One year, it wasn’t rented out to one. For whatever reason, that Fulbright scholar didn’t want to live in a traditional Japanese house – probably wanted to live in an apartment.

So it was advertised in the Tokyo Journal, I saw it, and I grabbed it. After a year, the landlord told me I’d have to move on because it’s going back to a Fulbright scholar again. But, by chance, I’d met an American woman who told me that I actually don’t have to leave. What you do is, you write a really nice letter to the landlord and say, “I couldn’t imagine ever leaving. You’re such a wonderful landlord,” something like that. You don’t bang your fist on the table and say, “I’m not leaving!” – nothing like that. It’s very civilized in Japan.

They’ll understand that you know your rights. So from then on it was all smiles, and for 10 more years I was able to stay in that house. Then, finally, the old landlord died. I can’t blame his son [for] wanting to cash in. He was going to cash in big-time. His mother, who had built the house with her late husband, thought that the house was going to be sold to the CEO of a big company who would live in this beautiful old house – that she and her husband had built.

But, no, it was going to be pulled down, and a big block of apartments was going to be built there. So she was really outraged that this Australian guy was holding out. I remember coming home one evening, and there was a lot of salt around the front door. I don’t know whether you know the tradition in Japan of throwing salt around to get rid of bad spirits. (laughs)

She was throwing salt at the door, and then one time she actually burst in with a broom: “Gonna kill him! Gonna kill him!” I had to try to defend myself without hurting her. There was even a time when the police were called. It wasn’t pleasant at all.

My feeling was that it wasn’t just the money. The idea that this beautiful old house and the two huge old cherry blossom trees – everything was going to be destroyed just because of this ridiculous real-estate bubble. And I thought, “I’m going to hold on here and prevent this atrocity.”

Eventually, the landlord’s son sold it to a jiageya. Usually, you don’t sell a property with a tenant still there because you’ll get less money – the buyer knows they will have to pay the tenant to move out. They tried to intimidate me, and I ended up having to deal with these chimpira kind of people and their attempts at intimidation.

I got myself a lawyer. As I was told, having a lawyer is like having a gun. Also, as a foreigner, there is a measure of safety; they’re not going to push things too far and create an international incident. So it became difficult for them, as their threats against me, as a foreigner, weren’t anything like they would be for a Japanese person.

Anyway, unbeknownst to me, I’d become quite well known in the real-estate business in Japan. I was this gaijin guy who was holding out. (laughs) I ended up getting a very big payout of about $600,000. The lawyer took 20%.

A friend of mine was visiting me and was given a lift by his Japanese friend who happened to be a real-estate agent. They pull up at the gate; he sees the address and says, “You guys are famous!”

Many years later, I’m living in a rural area in Australia, and my son is at preschool. The teacher at his preschool said, “My brother-in-law has just married a Japanese woman, and they’re moving to Australia. I’d like you to come and meet them and give some advice about being married to a Japanese person, having a child, and living in Australia.”

So Yoko and I and our son got in the car and headed out into the hills to this little hippie commune. I got out of the car, and some guy that I’d never seen before in my life comes running up to me and said, “I just wanted to shake your hand. You’re a legend!” This is more than 10 years on. Back in Japan, he’d heard the story, and the legend had probably grown over the years. (laughs) I’m there in the middle of the wilds of rural Australia, and this guy wants to shake my hand because I shook down the yakuza.

BH: Let’s go to the main movie that I wanted to ask about, Godzilla (1984). Let’s talk about that, if you remember how you got cast, and what you remember from that production.

NR: What I remember in particular was that I was given the daihon, which is the script, and it was all written in Russian. Obviously, I don’t speak Russian. Fortunately, it wasn’t written in Cyrillic script, but when I looked at it I thought, “There’s not enough vowels in here; there are too many consonants. How the hell am I going to pronounce this?” I had no idea how to pronounce it. So I went to the Soviet embassy, and a very nice lady there kindly offered to read my lines onto a cassette tape for me.

I listened to them over and over, over and over, and thus was able to pronounce my Russian lines. The director probably thought, “We could always overdub these guys.” And I suspect that some of the smaller-part guys – in fact, I’m pretty sure they’re overdubbed because their Russian sounds really good.

I know I wasn’t overdubbed because I can recognize my voice, and I’m pretty sure the commander [played by Dennis Falt] wasn’t overdubbed. It’s both our voices, but the other guys who were reading the instruments – I’m pretty sure they were dubbed.

I found it was quite common in Japan that I wasn’t asked upfront if I could do something – possibly because they had a back-up. Eventually, I learned that no matter what they ask, you say, “I can do it,” because you’ll be able to fake it in some way.

The set for my scene was very realistic. Well, I’ve never been on a nuclear submarine, but it sure did look like we were onboard a submarine. (laughs)

And then, when it was destroyed by Godzilla, the mayhem of the water pouring in was very realistic. And I tell you what, OH&S – occupational health and safety – is a big thing in Australia these days, and I’m sure it is in the States. But on that set there were very few safety precautions. Actually, that was the case in many of the jobs I did. I’ve spoken about playing with black-powder flintlock [pistols]. And then there was the job I did at Toho Studios in the pond that had been used for shooting training films for Japanese pilots during the Second World War.

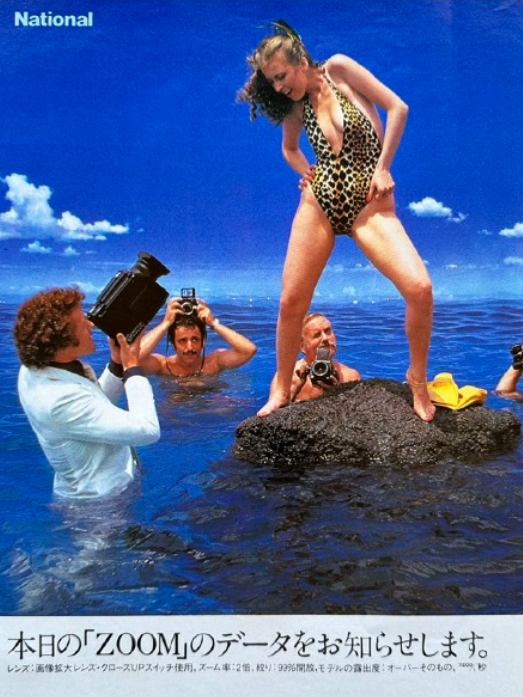

BH: That was for National video [cameras]?

NR: Yeah, yeah. I had to stand on a huge boom – one of those huge counter-weighted booms that a cameraman sits up on when shooting movies. They got the weight wrong, and I was thrown off. Luckily, I wasn’t badly injured, but they felt sorry for me, and they gave me the very nice white suit that the wardrobe department had dressed me in for the job. (laughs)

The set that they put up [for Godzilla], they got it moving like this, and then the water rushed in, and bodies were going everywhere.

BH: So it was kind of on hydraulics?

NR: Yeah, I think it probably was some mechanism like that. So they got movement happening, and we were all just desperately hanging on as the water rushed in. I’m really surprised nobody got hurt. The Russian woman who had recorded my lines for me actually came along to watch the shooting.

BH: She was from the embassy?

NR: From the embassy, yeah. See, in those days, it was a fairly small expat community in Tokyo, so even plebs like me found ourselves mixing with embassy people. I think everybody in the Soviet embassy had some spying role; everybody in the American embassy also fed information to their intelligence people.

When I lived in Laos, because I had short hair and didn’t look like the other hippies, some people thought I was a spook. I remember an anthropologist talking to me, and I eventually realized, “He thinks I’m an agent – CIA or whatever – and he wants me to employ him, pay him to provide information about the hill tribes.” These were the opium-growing ethnic minorities living in the Golden Triangle, which was rife with intrigue and covert operations by the CIA, as this was during the Vietnam, and [the] wider Indochina, War.

So the expat community in Tokyo mixed quite a lot. She came along for the shoot – I guess she must have got time off. She did tell me that I had got her Muscovite accent down pat. I don’t know about that; I think she was just being kind.

BH: She’s trying to recruit you, basically. (laughs)

NR: Oh, that’s a possibility. (laughs) [But] it wouldn’t be worth it. I stay well clear of anything political. It reminds me of an American friend in Laos. He was teaching a Russian family in Vientiane. and the CIA was trying to recruit him to report on anything that was happening in the Russian household. This was in spite of my friend having an FBI record for anti-American activity! (laughs)

Anyway, back to Godzilla. Was that the first Godzilla? No, it wouldn’t have been the first one.

BH: No, there had been several. It was a remake of the original, so it was starting the series over again, basically. But it was not the first one.

NR: The first Japanese woman I ever met, her father was doing special effects on monster movies in Japan. This was quite a number of years before I’d even arrived in Japan.

BH: So who was this?

NR: I don’t know. I met her in Singapore; it was just a short liaison. (laughs) And I don’t remember her name or anything like that. But it was funny that, years later, I end up in this monster movie. I didn’t really know about the Godzilla movies back then; I had no idea that Godzilla would become known in the West.

In fact, I never expected anything that I did in Japan would ever be seen outside of Japan, or that I’d find myself sitting here with somebody who’d seen my name in the credits that roll at the end of a movie.

I must say it was nice of the Japanese production company to put our names [in katakana] like that. We gaijin were usually just incidental to the story, but we were credited, which was very good of them. (laughs)

BH: Do you remember how many takes there were for your scenes in Godzilla?

NR: Well, obviously, that final one, there could only be one take because they’re destroying the whole set in doing it. In terms of the lines we spoke, I don’t think there were many takes at all.

BH: So people were nailing the Russian? No one was messing up?

NR: I don’t remember messing up on the Russian, nor the commander – I don’t think he messed up. The funny thing is that one of the things I do remember very strongly about most of my jobs is, directors endlessly saying, “Mo ichido! Mo ichido!” “One more take! One more take!” But I don’t remember that from Godzilla. I don’t remember endless takes.

BH: Was it all shot in one day?

NR: Yeah, my scenes were all in one day.

BH: Do you remember how long the water was rushing? Was that, like, a minute, 30 seconds?

NR: Probably only 30 seconds or so, but maybe it was a minute. It was pretty chaotic.

BH: Do you have any other memories? Do you remember the names of the other people in your scene?

NR: No, I don’t. Sorry! (laughs) I’ve got much better anecdotes about some of the non-Toho things.

BH: But that’s about it for Godzilla.

NR: Yeah. I don’t think I went to see it. Many years later, Yoko went online and got the DVD for me, and I [have] digitally sliced out my scene for my own records.

BH: I’ve got another question. In terms of studying [Russian], do you remember how long you studied it – how many days?

NR: It would have been a lot because [speaks some Russian lines from the film]. I can still remember some of it. It would have been a few weeks. The thing is, when you want to memorize anything, you repeat it, and you repeat it, and gradually extend the time between repetitions.

You want to have it in your long-term memory because, if you’ve just crammed it in, and it’s still in short-term memory, under pressure you’re going to blow it. It’s got to be laid down into long-term memory, and so that would have taken a number of weeks to do. Not that I was doing it constantly, but you start doing it intensively, then gradually ease off. That’s the best technique for learning something by heart.

BH: One of the last things I’ll ask about is, you did [Oretachi] Hyokinzoku (1981-89) with Beat Takeshi. What do you remember about Beat Takeshi at that time?

NR: I did a number of things with [Oretachi] Hyokinzoku; it was a lot of fun. I remember the first time I met Beat Takeshi. He had appeared in the movie Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence (1983), and I had just seen that movie. He played the part of Sgt. Hara, and he was so good. He was so frighteningly violent in that movie.

Ryuichi Sakamoto did the music, and the music was great. The soundtrack was great, but I didn’t think much of his acting.

When I went to the studios for the first time to play a part in Hyokinzoku, I recognized Beat Takeshi. I thought, “I can’t believe this guy is actually a comedian, yet he did that Sgt. Hara role?!” And I said to him, “I saw you in Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence, and you were great.” I wasn’t trying to lay it on, but I was just so impressed.

I remember him telling me he didn’t really understand what the director was trying to get at. Oshima, was it?

BH: Yeah, [the director was] Nagisa Oshima.

NR: He told me he didn’t really know what the director wanted, but I said, “You nailed it, man. You really did.” (laughs) The first thing I ever did for them was where I had the part of an American businessman being entertained by Beat Takeshi and Sanma Akashiya. Their job was to make me laugh because they wanted a sale – you take the foreign businessman out, you ladle him with alcohol, you give him a good time, and then he signs the contract.

So I’m sitting there, and I’m told I just have to keep a straight face and look bored and unimpressed by the antics of these two guys. And these guys are just laying it on, and they’re some of the funniest guys in Japan, and I’m supposed to just sit there. (laughs)

Eventually, of course, they make me laugh, and I thought, “Oh no, I’ve blown it!” But actually the way the Hyokinzoku team does it, they just keep the camera rolling, and whatever they get, they get, in spite of the fact we’ve deviated from the script. This experience really helped me with future programs I did with them, as I realized that there’s a lot of ad-libbing. It’s sort of free rein in a way. There’s a script, but you don’t necessarily keep to the script. Of course, the director’s got to like what you end up doing.

I remember going away on a shoot for a couple of days, and the whole crew was making gags and making each other laugh all the time, so being on the bus with them was a lot of fun.

But the interesting thing was, Beat Takeshi was a much quieter, more thoughtful kind of guy. He was only madcap in front of the camera, whereas Sanma-san was crazy all the time. Beat Takeshi was different. He’d often be off by himself and just thinking. Very different from the guy you saw in front of the camera.

BH: In 1990, you left Japan, so what made you leave Japan at that time?

NR: I’d had to move out of the beautiful house that I’d been in for more than a decade. We had the money from the “real estate deal,” and by that time I had quite a successful shiatsu business where I was teaching foreigners and making good money.

One of the things about acting and modeling is that it’s a tenuous existence because, if the phone doesn’t ring with a job, and you’ve got to pay the rent at the end of the month…

Since it’s a tenuous existence, you want to try to take [an]other job – some sort of regular income. And, if you do that, then, when the agency phones, and you have to say, “Look, I’d love to do it, but I’m tied up,” they eventually stop calling. You have to always be available.

So, gradually, I moved into a more secure way of making money, which was setting up my own little business. I was a little reluctant to start teaching shiatsu in Tokyo where my teacher, Suzuki-sensei, in whose class I was doing the interpreting, was based. So I went to him, and I said, “I feel bad about this, but I’ve been asked by people to teach shiatsu here in Tokyo.”

Fortunately, he gave me his blessing, which was really good of him. So, in a way, I became something of a filter. A lot of people wanted to study shiatsu in Japan, but they didn’t speak the language, and so they could start learning it from me. Those who showed promise I could then pass on to Suzuki-sensei. So my little teaching business became quite successful.

But then we got all the money from the real-estate deal, so the plan we came up with was that we’d go and do some traveling, then pop back to Japan, and I’d teach a couple of courses, make some money, then we’d do a bit more travel. The dream lifestyle was a third of the year in Japan, say, the nice weather – autumn and spring – forget the hot summer and icy midwinter.

In the Japanese winter, we’d be in the Southern Hemisphere, enjoying the Australian summer at the beach house, and then one third of the year we’d be traveling around the world. That was the plan.

I’d built up my shiatsu business over a number of years. I started off with just two students and ended up with many. So many, in fact, that I had to limit the class sizes to 12 students in each of my three classes. If you offer a good product, you’ll be successful. I built a reputation and got my students by word of mouth. I passed it over to a friend and said, “You teach the courses while I’m away, and then, each time I come back to Japan, I’ll teach the courses.”

But the thing is that, if you build a business yourself, you understand the work it has taken, and you appreciate what you have. If you just hand over what you’ve done to somebody else, they won’t appreciate what you had to put into it. Coincidentally, in the last course I did, there was an American journalist, and she wrote an article about this gaijin teaching shiatsu in Japan, and her article was run in the Tokyo Journal. My friend, who was to take on my classes, it was his phone number that was given in the article as the contact, obviously, because he was going to be teaching the next course.

He came home the day the article went to press, and his answer[ing machine] was absolutely chock-a-block with inquiries; in fact, the tape had run out. Suddenly, [with] this free advertising, he had classes overflowing with students. So he upped the price, and, within a fairly short time, he’d run the business down to nothing – because it’d been handed to him on a platter. So that part of the dream lifestyle didn’t quite work out as planned.

And then, when a child comes along, life changes. Such a lifestyle of travel and swapping countries is a lot more difficult when you’ve got a child. But, as I’ve mentioned before, when I went back to Australia, I was really keen to get back into physiology and looking for a scientific basis for acupuncture and shiatsu – all of these Oriental medical ideas I’d been exposed to.

That never eventuated, but I was also very interested in sustainable development and environmental issues, and that’s what I ended up doing. I put a lot of money, time, and effort into research projects for new agricultural methods, sustainable human settlement, and things like that. So that’s where I’ve ended up.